Empress Irene was the wife of Leo IV and, on her husband's death, she reigned as regent for her son Constantine VI from 780 to 790 CE. From 797 to 802 CE she ruled as emperor in her own right, the first woman to do so in Byzantine history. During her lacklustre reign, Irene ruthlessly schemed and plotted to keep the throne she would lose and regain three times, but she is chiefly remembered for restoring the Christian veneration of icons, which her predecessors of the Isaurian dynasty had sought so vehemently to repress. Even this seemingly pious campaign was really only a means for Irene to defeat her enemies and keep power. The Empress' gold coins reveal much of her duplicitous character for, uniquely, they carried a portrait of herself on both sides.

Early Life

Little is known of the young Irene except that she was an extraordinarily beautiful orphan girl from Athens, born c. 752 CE. Emperor Constantine V (r. 741-775 CE), holding an empire-wide beauty contest for the purpose, fished her from the obscurity of the provincial town that Athens had then become and arranged for her to marry his son, the future emperor Leo IV, who would reign from 775 to 780 CE. The wedding took place in 769 CE, and she immediately influenced state policy by tempering her husband's attacks on the Church's veneration of icons. Leo's short reign came to an end when he died of fever, aged 30, while campaigning against the Bulgars, but Irene's appetite for power needed further feeding.

Irene As Regent

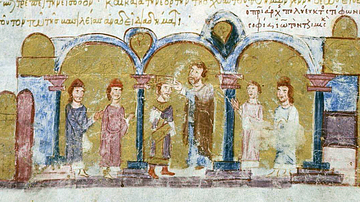

Constantine VI ruled from 780 to 797 CE, inheriting his title aged just nine. Ruling as regent for her young son over the next decade, Irene quashed a rebellion led by the sons of Constantine V, dismissed ministers and military men whose loyalty was questionable and made use of the experience of two court eunuchs, in particular, Staurakios and Aetios. The former was logothetes tou dromou or chief minister with a wide range of powers. In 783 CE Staurakios sent a Byzantine army to fight the Slavs in Greece, and the next year Irene enjoyed the first military successes of her reign against both Slav and Arab armies.

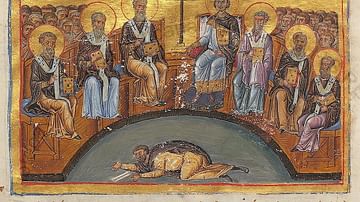

Religious affairs seem always to have been foremost in the regent's plans, and in 784 CE she made her former secretary Tarasios the Patriarch (Bishop) of Constantinople, despite him not yet being ordained. Next, Irene convened a Church council in Constantinople in 786 CE to put an official end to the destruction of icons (iconoclasm). However, influential members of the army were against such a move, and they organised a riot which forced the closure of the council meetings. The Empress was not to be deterred, though, and she swiftly stationed the troublemakers to Asia Minor under the guise of preparations for a new military campaign. Once abroad the army was disbanded and their positions of authority back home taken by those more loyal to the Empress.

With the army opposition dealt with, Staurakios accompanied Irene to the Seventh Ecumenical Council at Nicaea in September 787 CE. There Irene and 350 invited bishops finally ruled to restore the orthodoxy of the veneration of icons in the Christian Church and end iconoclasm. The persecution of iconophiles had been a key feature of previous emperors' reigns, especially Irene's father-in-law Constantine V, so the Empress could not be too harsh on the perpetrators and risk alienating family members at court. Instead, they were permitted to repent of their sins and welcomed back into the Church now glittering once again with its precious icons.

Exile From Court

When Irene made it be known that she intended to rule above her son Constantine no matter how old he was, many of those who opposed the restoration of icons, saw the dangers to the empire's army strength Irene's purges had threatened, and who believed Constantine had the rightful claim to the throne alone, rallied around the young emperor. Irene responded by throwing him in prison, but by 790 CE the army came to Constantine's support and released him. The army still contained many iconoclasts, and they had refused to swear loyalty to Irene alone on religious grounds. Now 19 years of age and keen to remove his interfering mother once and for all from state affairs, Constantine banished her from court along with her closest advisors while he engaged Michael Lachanodrakon, the influential general and governor of the Thrakesion region of the empire. After a decade in the shadows, Constantine took his rightful place at the apex of Byzantine government.

Unfortunately, the young emperor was not actually up to the task. Serious and immediate defeats against the Bulgars and a shameful truce against the Arabs did nothing to aid his popularity, and conspiracies at court were rife. One led by Constantine's uncle Nikephoros was quashed, and the emperor blinded the ringleader in an all too familiar act of imperial Byzantine brutality. Constantine then ordered the tongues of all four of his uncles to be torn out. It was a rare moment of decision, but it was too little, too late.

Irene was not to be so easily ushered to the wings of power, either, and she returned to the court in 792 CE, invited by her son as a last-ditch attempt to restore some order to his reign. In effect, they ruled jointly for the next five years, but Irene soon began to plot against her son. Significantly, Constantine could no longer call on the support of Michael Lachanodrakon, the general having been killed that year while campaigning against the Bulgars. The army was all too unimpressed with the young emperor, and his popularity plummeted even further when he began to blame his soldiers for their defeats, taking the ill-advised action (cunningly suggested by Irene, of course) of tattooing the word “traitor” on the faces of 1,000 of them.

A final crushing blow to Constantine's ambitions was the protests following his divorce and subsequent marriage to his mistress Theodote, the so-called Moechian Controversy, in 795 CE. To make matters worse, the couple had a son 18 months later. Two monks were especially vociferous in their outrage at the emperor's behaviour as head of the Church, Plato of Sakkoudion and Theodore of Stoudios, who both claimed that his divorce was illegal and so in marrying again the emperor had committed adultery. The emperor had lost the support of the one group he could always depend on; the iconophiles. Constantine's unpopularity with his people and the Byzantine establishment meant that he had no friends left to block his removal from power by his own mother.

Return As Empress

In 797 CE, when Irene took back the throne for herself, she blinded her son, doing so in the same purple chamber of the palace in which he had been born. There was not going to be another rebellion against her rule. Constantine died shortly afterwards, almost certainly as a result of his injuries, which were intended to kill not maim. With his heir having already died earlier the same year, Irene now had dealt with all her challengers. Thereafter, Irene is referred to in official state records as basileus, emperor, and not as empress, the first woman to so rule in her own right.

She continued to take an interest in all matters of her empire: politics, warfare, and religion combined and tried to win favour by announcing reductions in taxes for her people. She was not without her troubles, though, as rebellion was still in the air and was given focus by the surviving, albeit maimed, sons of Constantine V. The Arabs had to be paid off to avoid further invasion, all but bankrupting the state, and the people could never quite forgive her for her crimes, even if she did provide soup kitchens for the poor and accommodation for the elderly. Riding around Constantinople in a golden chariot launching coins into the crowds did not help much either. Troubled times were in store for Byzantium's most ambitious and ruthless of sovereigns.

In early 802 CE, Irene attempted a marriage of alliance with the Franks' king Charlemagne, who was also the newly declared Emperor of the Romans in the west, and who, likewise, was in favour of once more unifying the two halves of the old Roman empire. A similar plan had already been attempted when Irene had arranged for her late son to marry Rotrud, the daughter of Charlemagne, but Irene had broken off the engagement in 787 CE. However, the new approach to join the two families met fierce opposition, especially from the powerful eunuch Aetios in Constantinople. It simply would not do for a Byzantine emperor to marry an illiterate barbarian, even if he had been blessed by the Pope and wore spectacular red tights.

In October 802 CE the highest court officials in Constantinople convened in the Hippodrome and declared the Empress surplus to requirements. Irene was removed, exiled to a monastery on Lesbos and succeeded by Nikephoros I, one of the Empress' former finance ministers. Irene died within a year of losing the throne she had loved so much and clung onto for so long. The historian J. J. Norwich gives this grim assessment of Irene's reign:

Scheming and duplicitous, consumed by ambition and ever thirsty for power, she brought dissension and disaster to the Empire, being additionally guilty of one of the foulest murders that even Byzantine history records. (115)

Nikephoros would reign until his death in battle in 811 CE, unable to halt the decline of the Byzantine empire as Charlemagne's own empire rose in the west and the Muslim Abbasids threatened from the east. The cycle of royal assassinations that Irene began with the murder of her son would keep on turning so that the Byzantines would see six emperors in the space of 15 years.