The encomienda was a system where Spanish adventurers and settlers were granted the legal right to extract forced labour from indigenous tribal chiefs in the Americas colonies of the Spanish Empire. In return, the Europeans were expected to give military protection to the labourers and offer them the opportunity to be converted to Christianity by funding a parish priest.

The encomienda system permitted the Spanish Crown to convert its invading army of conquistadors into colonial settlers, but the system's flaws – maltreatment and significant population reductions from diseases – meant that it was eventually replaced by a system of low-paid labour and large estate management.

Feudal Origins

The Spanish Empire maintained two key objectives in conquered territories: extract material wealth and convert the indigenous peoples to Christianity. Under the category of resources the Spanish saw fit to exploit came the labour of any local peoples in the area. Encomienda was a feudal term which derived from the verb encomendar, meaning "to entrust". In medieval Spain, encomienda referred to the relationship between a landowner and those who worked the land. In a reciprocal relationship, the former received labour while the latter received protection. This concept was applied to land taken back from the Moors during the Reconquista and the colonization of the Canary Islands. Encomienda was then extended to the Americas colonies from 1502 (first in Hispaniola) as a way to justify what amounted to little more than slavery. In 1503 the policy received royal approval, and it spread from the Caribbean to Mexico and Central America, and then to South America as the conquistadors ("conquerors") used it as a means to extract resources and as a reward for their followers.

In a rather dubious justification for exploitation, a favoured European (encomendero) could benefit from free labour for any purpose whatsoever in return for offering local people a certain level of physical protection and an opportunity to be exposed to the Christian religion and so enjoy the ultimate salvation of their souls.

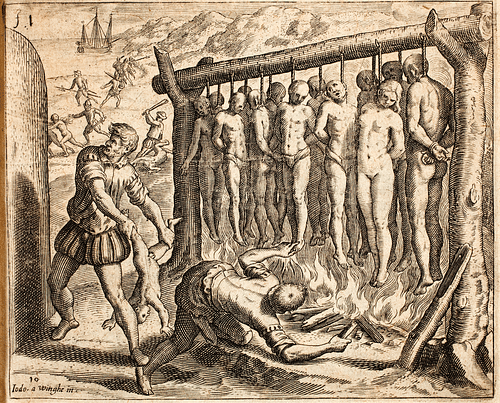

The encomienda was not then slavery of American Indians, which the pope had prohibited in 1537 (although they did not so favour Black Africans). The European attitude might have eased a few consciences on their side, but, naturally, the indigenous peoples did not often see the relationship in these terms, and thousands suffered what was, in practical reality, slavery in all but name. Further, "there is ample evidence that encomenderos largely ignored their religious responsibilities" (Alan Covey, 372).

There was no connection with land as part of the encomienda as there had been in medieval Spain, instead, in the colonies, encomienda was purely a legal arrangement, and the right could even be held by municipalities. An encomienda was initially given by leaders of conquistador expeditions and then either the viceroy or the audiencia (judicial panel) present in the nearest large town. The size of the population tied to a particular encomienda varied; most involved around 2,000 family units, but some could be much larger, such as that assigned to Hernán Cortés in Mexico, which encompassed well over 23,000 family units. Certainly, even a smaller encomienda permitted a settler to have a house built, feed his family, and maintain a small entourage of personal followers (paniaguados) for his own protection against rebel native peoples – raids on Spanish settlements where the inhabitants and animals were all slaughtered were not uncommon. The indigenous peoples roped into the labour were given protection from other European settlers and adventurers. Regarding the wider community, the holder of the encomienda was expected to send his armed followers to help defend the local settlement if required and to pay for a parish priest.

An encomienda was usually granted for life but was not hereditary, despite calls for it to be so by holders of the right and some religious orders. It was believed that if settler families had an extended relationship with their labourers, they would treat them better. The call for hereditary encomiendas was rejected by the Crown as it wished to keep its options open and maintain its overall control of the colonies. Consequently, in the majority of cases, the encomienda of a deceased holder reverted to the Crown with a small provision made to a surviving widow and any children.

Labour v. Souls

Initially, the right of encomienda was given to an adelantado, that is a conquistador who had been awarded the license to explore and conquer new territories on behalf of the Spanish Crown. The adelantado could keep 80% of any wealth he acquired in the process (the Crown got the remaining 20%), and this included a right to use local labour. The encomienda was then extended to settlers so that, in effect, an invading army was transformed into a quasi-militia urban population that earned wealth from land worked by indigenous peoples in the surrounding area.

There were intense debates in Spain throughout the 16th century as to which of the often conflicting aims of material gain and religious conversion should be regarded as the most important. The 1512 Laws of Burgos set out how indigenous peoples should be treated and the responsibilities of settlers as Christians. Then the Council of the Indies in Spain, which supervised all aspects of the colonies, issued directives that local people should not be exploited to the point of starvation and death. The issue was discussed in a meeting of the Council in 1540, where the members were urged by President Loaísa to consider the following six questions:

- How should those who had treated Indians badly be punished?

- How could Indians best be instructed in Christianity?

- How could it be guaranteed that Indians would be well treated?

- Was it necessary for a Christian to take into account the welfare of slaves?

- What should be done to ensure that governors and other officials carry out the government's orders to be just?

- How could the administration of justice be properly organised? (Thomas, 474-5)

From the Spanish Crown's point of view, the arrangement of encomienda created an inherent conflict of interest. Monarchs were expected, as defenders of the faith and beneficiaries of the goodwill of the popes, to promote the Christianization and 'civilization' of conquered peoples. This naturally meant that killing them with labour was hardly conducive to religious education and conversion. On the other hand, to maximise the extraction of wealth from the colonies, labour was desperately needed for such large state projects as mining precious metals and harvesting crops grown on an industrial scale.

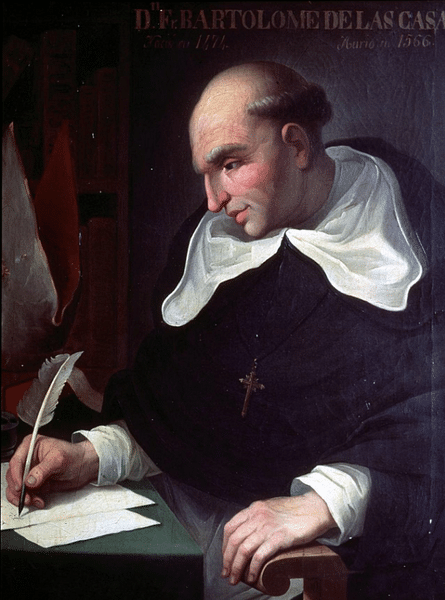

The third group in this triangle of control was the Europeans who had been granted the right of encomienda. Thousands of miles from the monarchy and the Council of Indies, many conquistadors saw no need for niceties as they ruthlessly exploited both local resources and people for their own personal gain. There were protestations by indigenous community leaders and certain members of the Spanish religious orders like the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1566), who wrote a graphic description of just what was going on in the New World in his A Very Brief Recital of the Destruction of the Indies of 1522. On the ground, these voices could do little to prevent encomienda becoming, in many cases, a system of extreme forced labour indistinguishable from slavery with the exception that the labourers could not be sold. Further, indigenous American peoples were very often completely unsuited to the alien concept of labouring for another in regular working hours, and the increased contact with Europeans only led to even more devastation of the American population by European diseases. The population of Hispaniola was perhaps around 200,000 before European contact, but by 1522, it had been reduced to 90,000; that of New Spain had been around 22 million in 1500 but was reduced to just 3 million by 1550. Either by hard labour or disease, the fate of the local peoples was grim.

Protest & Change

The situation became so serious for the stability of internal affairs and European-Indian relations that there was even a move to abolish the encomienda in 1542. A set of New Laws attempted to reduce the application of the encomienda but made little headway against the powerful and avaricious forces of monarchy, conquistadors, and settlers who were making a fortune out of the system. In 1573, a more substantial attempt at limiting exploitation was made by Philip II of Spain (r. 1556-1598). The monarch outlawed any use of the encomienda system in any new territories. This hardly helped indigenous peoples already suffering under the system, but it at least indicated a realisation that the system was flawed and could not continue indefinitely. The Americas colonies of Spain were now becoming an area no longer of conquest but pacification.

As the colonisation process evolved and the collaboration of indigenous and mixed-race citizens became essential, so the encomienda system slowly came to an end by the first years of the 18th century (but continued until the 1780s in some pockets of the empire, notably Chile and the Yucatán peninsula). One of the problems with the encomienda system was that there were not enough licenses to meet demand, and in wilder areas, the indigenous peoples, unsurprisingly, proved reluctant to volunteer for such a system. The level of productivity the system could provide given the reduction in labourers due to diseases over time and the unsuitability of native crops for urban markets now feeding Europeans meant that new ways had to be found to ensure agricultural production met the demands of colonial settlements.

The encomienda was replaced by the repartimiento system, which also involved forced labour, but at least this time the workers received a wage, albeit a low one. Known as mita in the Viceroy of Peru, this system obliged indigenous leaders to send a fixed number of male labourers to work for the colonial administration (just as the Aztecs and Incas had done in their own empires). The team usually worked for a number of weeks before being replaced by another group from the same community. The scheme permitted the continued operation of mines and state-run agriculture and the construction of infrastructures such as roads, bridges, and public buildings. The low wages were a poor compensation for being uprooted from one's family and community, but it was a step forward in comparison to the encomienda system. A second alternative to encomienda was the use of slaves shipped to the Americas from Africa. Both slaves and low-wage labour allowed European settlers or settlers of European descent to evolve a new system of managing land and resources, which involved establishing vast estates or haciendas where agriculture (wheat, sugar, olives, and vines), stock-raising (imported cattle and sheep), and mining (gold and silver) were conducted on an ever-larger scale.