The English Civil Wars (1642-1651) witnessed a bitter conflict between Royalists ('Cavaliers') and Parliamentarians ('Roundheads'). The Royalists supported first King Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) and then his son Charles II, while the Parliamentarians, the ultimate victors, wanted to diminish the constitutional powers of the monarchy and prevent what they considered a Catholic-inspired plot to reverse the English Reformation.

Parliament, led by such figures as Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), had superior resources and a more professional fighting force – the New Model Army – which ensured the Royalists ultimately lost the three civil wars fought in England, Ireland, and Scotland (hence the alternative name of 'Wars of the Three Kingdoms'). Tried for treason and found guilty, King Charles was executed, the monarchy was abolished, and England was proclaimed a republic with Cromwell at its head as Lord Protector.

Causes of the Conflict

The causes of the English Civil Wars were many and varied, changing as the war progressed. Indeed, such was the complexity of the conflict, it is often divided into three distinct phases:

- The First English Civil War (1642-1646)

- The Second English Civil War (Feb-Aug 1648)

- The Third English Civil War or Anglo-Scottish War (1650-1651)

The war was only the fighting phase of a struggle that went back to the very first year of Charles I's reign in 1625. King Charles' lack of compromise and unshakeable belief in his divine right to rule had brought him into direct and persistent conflict with an equally strong-willed Parliament that wanted a greater role in government. Parliament also wanted to prevent what it considered a steady return to Catholic practices in the Anglican Church masterminded by such Arminians as William Laud (1573-1645), the Archbishop of Canterbury. Many MPs were Puritans, and of these, the Independents or Congregationalists dominated. They wanted less power in the hands of bishops, more inclusion in the Church, and greater freedom for 'independent' congregations that assembled according to the individual believers' consciences and their own interpretation of the Bible.

The abolition of the monarchy was not the objective for the majority of MPs but rather a removal of what were considered the king's evil counsellors and a limit on his powers, particularly in terms of finance and raising taxes without Parliament's consent like the Ship Money to raise funds for warships. These grievances and others were presented by Parliament in the Petition of Right of 1628. The king, on the other hand, saw no need for Parliament and did not call one at all between 1629 and 1640, the period now called his 'Personal Rule', which began after his rejection of the Petition of Right.

Events came to a crisis point in 1639 when a Scottish army invaded northern England, the beginning of the Bishops' Wars (1639-40). These warriors were known as the Covenanters because they had signed a covenant swearing to defend the Scottish Presbyterian Church and its organisational head, the Kirk. Charles had made several unpopular moves to change religious practices in Scotland, including imposing a new Book of Common Prayer in 1637. In order to raise an army capable of defending his kingdom, Charles was obliged to recall Parliament. MPs seized this opportunity to forward their case to limit the king's powers. However, Charles dismissed what has become known as the Short Parliament after three weeks (April to May 1640). The Scots did not go away, though, and the king still needed money. Consequently, another Parliament was called in November 1640, and this was more successful, so much so, it became known as the Long Parliament. Then a second crisis arrived: a major rebellion in Ireland against English-Protestant rule, and so the king again needed funds for yet another army.

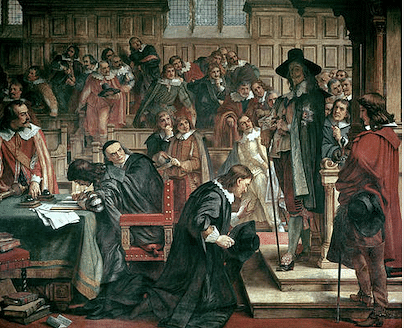

When MPs again presented their grievances concerning the king's rule, this time in the Grand Remonstrance of November 1641, Charles once more rejected them. The king, it seems, could not compromise, and he was still smarting at Parliament's trial and execution of his closest advisor Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Stafford (1593-1641) in May 1641. Stafford had been accused of preparing to bring an Irish army into England to aid the king, for which there was not much evidence, but it was a symptom of the atmosphere of distrust between the sovereign and many of his MPs. The king then shredded completely any remaining fragile threads of trust between the two sides when, in January 1642, he entered the sanctity of Parliament with a group of armed men and attempted to arrest the five MPs he considered most responsible for the Remonstrance. The five men, who included John Pym (1584-1643), a firebrand Puritan who was the king's most vocal opponent in Parliament, had been warned beforehand and were not there to be arrested. Still, even at this stage, not all MPs were against the king, and the division in Parliament over how to proceed with the crisis of government encouraged Charles to search for a military solution to what had hitherto been a conflict of only words. Both sides began to assemble their resources.

Battles & Sieges

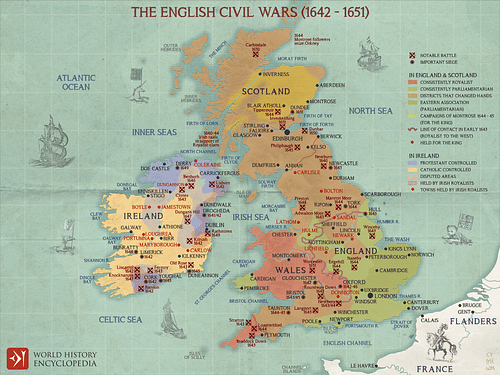

By August 1642, Charles had established himself in Nottingham where a royal army was formed. The Royalists controlled the southwest and north of England with the port of Newcastle and the valuable coal of the region. Parliament controlled London, the Royal Navy, and southeast England. The two sides became known as the 'Cavaliers' (Royalists) and 'Roundheads' (Parliamentarians). The latter name derives from some Puritans wearing their hair very short, but this only pertained to the early period of the war, in reality, many officers on both sides wore long wigs and extravagant clothing.

The English Civil Wars involved over 600 battles and sieges, although many of these were small in scale. The first major engagement was at the Battle of Edgehill in Warwickshire in October 1642. Artillery, cavalry, pikemen, musketeers, and dragoons combined in a bloody engagement that took 1,500 lives. Prince Rupert, Count Palatine of the Rhine and Duke of Bavaria (1619-1682), the king's nephew, led the Royalist cavalry with aplomb but then wasted time and effort looting the enemy's baggage train. Parliament made better use of its reserve forces, and the battle ended, like so many more battles to come, in a draw. The king could then have marched on London but dithered at Banbury and Oxford, which gave Parliament time to regroup and raise the city's militia force, the London Trained Bands. Charles then withdrew to Oxford which was made the Royalist capital.

Ten more major battles followed in the first half of 1643, and then, in July, Prince Rupert again came to the fore in the successful Storming of Bristol, a key port and armoury. The First Battle of Newbury in September 1643 saw 15,000 men fight on each side in the longest battle of the war, but it ended in another draw. Meanwhile, there were major sieges at Gloucester (Aug-Sep 1643), Hull (Sep 1643), and then York (Apr-Jul 1644).

The Parliamentarians had received a great boost in December 1643 when they signed an alliance with the Scottish Covenanters. The next significant engagement was the Battle of Marston Moor in July 1644, the largest battle of the war with over 45,000 men in the field. It ended in a great victory for the Parliamentarian forces. Marston Moor witnessed the skills of one rising new cavalry commander: Oliver Cromwell. The victory and the fall of York just after gave Parliament control of northern England with only a few isolated but, nevertheless, well-garrisoned castles still loyal to the king. Charles was at least boosted by the end of the rebellion in Ireland, which released some troops, but not a great many, for his cause.

Next came the Second Battle of Newbury in October 1644. The result was indecisive when a superior Roundhead army should have won victory. This missed opportunity led to bitter recriminations and the decision by Parliament to reorganise its forces into a more professionally trained and led army. The result was the New Model Army. Meanwhile, negotiations did take place between the two sides at Uxbridge in early 1645, but these came to nought. Parliament's long list of demands, the Uxbridge Propositions, was, unsurprisingly, rejected by the king. It may be that both sides were merely playing for time to regroup their armies after Newbury.

The Model Army's first major test came at the Battle of Naseby in Northamptonshire in June 1645. Led by Sir Thomas Fairfax (1612-1671) and with Cromwell once again showing his mastery of cavalry tactics, the New Model Army won a crushing victory that destroyed the king's infantry. The king fled to Wales and then to the far north of England. At the Siege of Bristol in 1645, the Royalists lost their main port. With a few more battles, culminating in victory at the Battle of Stow-on-the-Wold in March 1646, so ended the First English Civil War. However, the capture of Charles' personal writing cabinet at Naseby revealed the monarch had no intention of ever negotiating for peace and was even trying to engage Catholic troops from Ireland to fight on for his cause.

The Second Civil War

The words of Edward Montagu, Earl of Manchester (l. 1602-1671), now seemed to ring truer than ever: "If we fight a hundred times and beat him ninety-nine times, he will be the King still" (Hunt, 149-150). Charles was not going to give up and so the Second Civil War began. The summer of 1648 saw the Siege of Pembroke, the Battle of Maidstone, and the Siege of Colchester, but by August, the king's fortunes would plummet to new depths. The king had fled to the north of England, but he was handed over to the Parliamentarians in January 1647. He then escaped his confinement and established himself on the Isle of Wight to continue to direct the war from there. The Scots then became his allies as the Covenanters now considered the Puritan Parliament a greater threat to Presbyterianism than Charles. In December 1647, the king had signed the treaty known as the Engagement where he promised to promote the Presbyterian Church in England. The king hoped the Scots would invade the north of England and that rebellions would arise in southeast England and Wales. This determination to continue the war lost him more supporters. The king was seen as a warmonger who would not accept defeat.

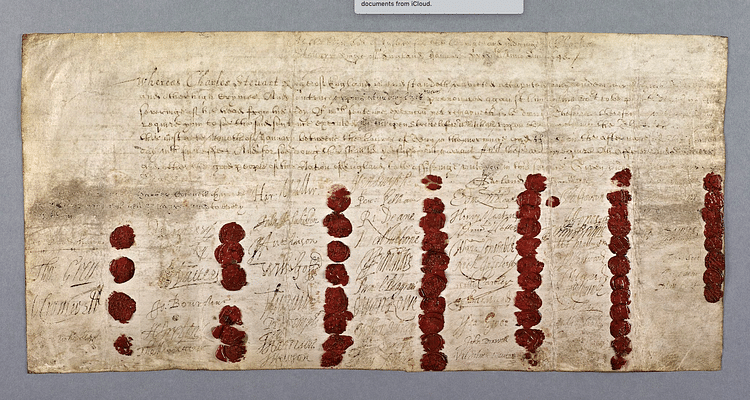

The planned Royalist uprisings were easily crushed or prevented altogether. At the Battle of Preston in August 1648, the New Model Army, led by Oliver Cromwell, won a great victory against the Anglo-Scottish Royalists. After Preston, Cromwell recaptured Berwick and Carlisle, and he took Pontefract, bringing this brief second war to a close. The king was brought to London from the Isle of Wight, put on trial in January 1649, and, found guilty of treason, he was executed on 30 January. The institutions of the monarchy and the House of Lords were abolished, and England became a republic. For these reasons, the events of 1649 are often called the 'English Revolution', although some historians disagree since the middle and lower institutions of government remained much the same. Crucially, though, the monarchy was not abolished in Scotland, where the late King Charles' eldest son became Charles II of Scotland. The civil war was not quite over yet.

Third Civil War

As the third war got started, Parliament had its hands full dealing with a major rebellion by pro-Royalist forces in Ireland. In the late summer of 1649, Cromwell led 12,000 men of the New Model Army and crushed the rebels with utter ruthlessness. The next main engagement of this third phase of the civil war was the Battle of Dunbar in September 1650.

After Ireland, Cromwell returned to lead the New Model Army into Scotland, where Dunbar, just across the border, became his supply base. Cromwell tried several times to attack Edinburgh but was not successful, and then, while retreating to Dunbar, the Scottish pursued the invaders. Cromwell could very easily have been trapped, and his army faced disaster, but the poor positioning of Scottish troops meant he could, once again, use his superior heavy cavalry to winning effect. Around 3,000 Scots were killed and perhaps 6,000 taken prisoner after the battle. Edinburgh was then captured on Christmas Eve of 1650. The remaining Scottish army was defeated at the Battle of Worcester in September 1651. So ended the English Civil Wars. Charles II fled to France. In England, Oliver Cromwell eventually became Lord Protector, head of the military state known as the 'Commonwealth' Republic that lasted until 1660 and the Restoration of the Monarchy that saw Charles finally crowned King of England.

Impact of the Wars

The impact of the English Civil Wars was enormous and long-lasting. Around one in four males in England and Wales were actively involved in the fighting. Non-combatants had to endure high taxes, confiscation of their land and property, destruction of their crops, forced labour to build defences, and deadly diseases brought by soldiers. One in ten people in urban areas lost their homes. Around 100,000 soldiers died during the conflict and another 100,000 civilians. Taken as a proportion of the then population, these deaths were greater than those sustained in the First World War (1914-1918).

The political ramifications of Charles I's execution and the abolition of both the monarchy and the House of Lords may seem short-lived when considering the Restoration occurred just nine years after the last battle. However, the political landscape was changed forever since the political struggles leading up to the war had greatly increased the powers of Parliament, and these remained thereafter. Cromwell's Acts of Parliament while Lord Protector were reversed, but King Charles II was now a monarch whose rule must be shared with the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

The Civil Wars were also a religious struggle. The Anglican Church was reformed, with bishops, clerical courts, and the Book of Common Prayer all swept away. The boom in printed literature provoked people's minds into considering just what should be the obligations and responsibilities of those who governed them both in politics and in religious life. A great number of religious groups were born, some of which gave women equal rights of participation, as "the war split the country by conscience uninformed by class" (Morrill, 370). There was an atmosphere of freedom of thought like never before as state and Church censorship became impossible to apply, such was the quantity of new works being printed by men and women. The Lord Protector did steadily impose more radical Puritan practices in churches, but misguided policies like prohibiting the celebration of Christmas did nothing for Cromwell's popularity. Many were happy to see the monarchy return in 1660 as they hoped for a return to the old days of peace and stability before this terrible conflict had ripped the three kingdoms apart.