Eros was the Greek god of love, or more precisely, passionate and physical desire. Without warning Eros selects his targets and forcefully strikes at their hearts, bringing confusion and irrepressible feelings. In the words of Hesiod, he "loosens the limbs and weakens the mind'" (Theogony, 120).

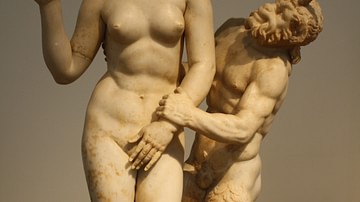

Eros is most often represented in Greek art as a carefree and beautiful youth, crowned with flowers, especially of roses which were closely associated with the god. Eros and Psyche are a common pairing in the sculpture of ancient Greece and Rome.

Who are Eros' Family Relations?

According to Hesiod in his Theogony, Eros was one of the primaeval gods who, along with Chaos and Gaia (Earth), was responsible for the Creation. Here he perhaps represented a universal love. In other traditions, such as the Orphic cosmogonies, Eros is born a hermaphrodite from an egg which was put by the Titan Chronos (who represents Time) into the womb of Chaos. The Greek comic playwright Aristophanes (c. 460 - c. 380 BCE) uses the same idea but has Eros hatch out from a silver egg laid by Nyx (Night) and Aither (Wind). Yet more alternatives for the mother of this highly desirable love child are Eilithyia (who protected childbirth), Penia (Poverty), and Iris (the messenger goddess and West Wind).

More commonly than all these other versions, though, Eros was regarded as the winged acolyte or assistant of Aphrodite, goddess of Love, Beauty, and Desire. He was also sometimes regarded as the child of Aphrodite, with Ares, the god of war, as his father, and his brothers were Deimos (Fear), Phobos (Panic), and Harmonia (Harmony). In some traditions, Eros also had a younger brother - Anteros - who was a much darker figure and an avenger of unrequited love.

Associations of Eros

In the Greek myths, Eros was associated above all with fertility, desire and sexual love, and because such passions could prove very difficult to control, the god was considered something of a cunning trickster. Sometimes the god is playful and harmlessly mischievous but at other times he is cruel with his surprise attacks that bring only reckless passion and confusion, the god toying with his victim as with a helpless leaf caught in the winds. The lack of discipline and general unreliability of Eros may explain why he was never considered one of the 12 Olympian Gods. Finally, Eros was considered the specific protector of homosexual love.

Eros & His Arrows

It was thought that Eros' arrows, often randomly aimed, made people, heroes, and gods fall in love - no one was immune. One of the most famous episodes involving this trick was when Apollo ridiculed the skills of Eros as an archer and the latter fired one of his arrows at the great god, making him fall in love with the nymph Daphne. Another such instance of Eros using his love-carrying arrows was when he made Medea fall in love with the great hero Jason, he who grabbed the Golden Fleece. Eros was not himself immune to the powers of love, and he famously fell for and married Psyche against the wishes of his mother Aphrodite.

In Greek religion, Eros was the subject of cult worship in Thespiae (with its sporting and artistic festival, the Erotidia) and at Athens, Megara, Philadelphia, Leuctra, Velia, and Parium. In addition, he was closely associated with many of the cults of Aphrodite across the Greek world. Altars to Eros were placed at both the Academy of Athens and the gymnasium at Elis, indicative that the love of male beauty was held in just as high regard as female beauty in the Greek world. As the god was associated with a manly love of courage and endeavour, warriors like the famous Sacred Band of Thebes, the elite fighting unit composed of homosexual pairs, held the god in particularly high regard and made offerings to Eros prior to battle.

Eros In Greek Philosophy

Eros and his omnipotence was a favourite subject of such philosophers as the Epicureans, Parmenides, and of Plato who discusses him at length in both his Symposium and Phaedrus. Plato, or perhaps more accurately the characters in his Socratic conversations, often champions the power of Love, as here:

Therefore I say Love is the most ancient of the gods, the most honoured, and the most powerful in helping men gain virtue and blessedness. (Symposium, 180b)

Again, in another work, the philosopher highlights the relation between Love and Good:

And if, as before, you investigate the matter by relying on old Attic, you will get a better understanding since it will show you that the name 'hero' (hērōs) is only slightly altered from the word 'love' (erōs) - the very thing from which the heroes sprang.

(Cratylus, 398d)

While in this passage Plato describes the causes and effects of love on a person once struck by Eros' arrows:

Think how a breeze or an echo bounces back from a smooth solid object to its source; that is how the stream of beauty goes back to the beautiful boy and sets him aflutter. It enters through his eyes, which are its natural route to the soul; there it waters the passages for the wings, starts the wings growing, and fills the soul of the loved one with love in return. The boy is in love, but has no idea what he loves. He does not understand, and cannot explain, what has happened to him. It is as if he had caught an eye disease from someone else, but could not identify the cause; he does not realize that he is seeing himself in the lover as in a mirror. So when the lover is near, the boy's pain is relieved just as the lover's is, and when they are apart he yearns as much as he is yearned for, because he has a mirror image of love in him - 'backlove' - though he neither speaks nor thinks of it as love, but as friendship. Still, his desire is nearly the same as the lover's, though weaker: he wants to see, touch, kiss and lie down with him; and of course, as you might expect, he acts on these desires soon after they occur.

(Phaedrus, 255c-e)

Finally, Plato also quotes an old saying by Homeric authors on Eros' more physical aspect:

Yes, mortals call him powerful winged 'Love';

But because of his need to thrust out the wings,

the gods call him 'Shove.'

(Phaedrus, 252b)

How is Eros Represented in Art?

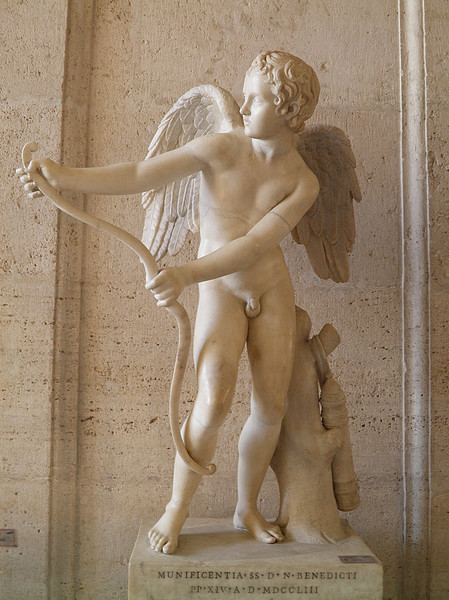

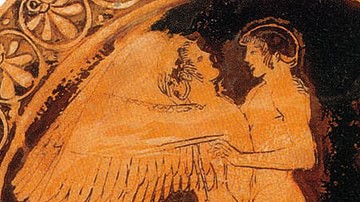

In ancient Greek art from the 6th century BCE, Eros is usually depicted as an adolescent with wings and he often carries a wreath of victory. He may also hold a lyre, a hare, or a whip, the latter when in pursuit of a youth. Surprisingly, he is only depicted carrying a bow with any great frequency from the 4th century BCE, although the first literary reference is much earlier and found in the tragedian Euripides' Iphigenia in Aulis (c. 406 BCE). On Greek pottery Eros usually appears at weddings and other romantic scenes, often hovering above the main protagonists such as Paris and Helen of Troy. Athletic and military scenes may include the impish god, too, and he regularly features in scenes of Aphrodite's birth and the creation of Pandora, the first woman in Greek mythology.

Figures of Eros can also appear in twos or threes, when they are referred to as Erotes, symbolic of the different forms love can take. When in a group, these are often given the individual names of Eros, Himeros (Desire), and Pothos (Yearning or Longing). Pausanias, the 2nd-century CE Greek traveller, describes a temple to Aphrodite at Megara in Western Attica with an ivory statue of the goddess of love, the oldest in the temple, and the trio of Eros, Himeros, and Pothos made by the famed 4th-century BCE sculptor Scopas of Paros. Elsewhere, Eros famously appeared on the base of the throne of the Statue of Zeus at Olympia which was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World and he is present, too, on the east frieze of the Parthenon, shown as a child next to Aphrodite. In works of the opposite scale, Eros was a favourite subject for Greek jewellers and gem carvers. In Hellenistic art, Eros and Psyche are often paired, and the favourite medium is terracotta figurines. It is only in later Roman art that Eros, under his new name Cupid, is commonly portrayed rather unflatteringly as a chubby and mischievous baby.