Esarhaddon (r. 681-669 BCE) was the third king of the Sargonid Dynasty of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. He was the youngest son of King Sennacherib (r. 705-681 BCE), and his mother was not the queen but a secondary wife, Zakutu (also known as Naqi'a-Zakutu, l.c. 728 to c. 668 BCE). He is best known for rebuilding Babylon which was destroyed by Sennacherib.

Esarhaddon is mentioned in the Bible in II Kings 19:37, Isaiah 37:38, and Ezra 4:2. Besides his restoration of Babylon, he is also known for his military campaigns in Egypt and assuring a smooth succession for his son Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE). An avid follower of astrology, he consulted oracles on a regular basis throughout his reign, far more than any other Assyrian king.

He claimed the gods had ordained him to restore Babylon and cleverly omitted from his inscriptions anything that would implicate his father in the city's fall, thereby presenting himself as a benefactor with no personal interest in the project. In his diplomatic letters he seems equally careful to characterize himself as a just and objective monarch. He maintained, then enlarged, the empire his father had left to him and his reign ensured stability and prosperity in the region. He died on campaign in Egypt in 669 BCE and left the throne to his son, Ashurbanipal, the last great king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Ascent to the Throne

Sennacherib had over eleven sons with his various wives and chose as heir his favorite, Ashur-nadin-shumi, the eldest of those born of his queen Tashmetu-sharrat (d.c. 684/681 BCE). Esarhaddon, born in 713 BCE, was the son of Zakutu, one of Sennacherib's secondary wives. Sennacherib appointed Ashur-nadin-shumi to rule over Babylon and, while fulfilling his duties, the prince was kidnapped by the Elamites and taken to Elam. Sennacherib mounted an enormous expedition to retrieve his son but was defeated. It is thought that Ashur-nadin-shumi was then killed by his captors sometime around 694 BCE.

After the defeat of the Assyrian army by the Elamite coalition, Sennacherib returned to his capital at Nineveh and busied himself with building projects and running his empire. He needed to choose a new heir but seems to have taken his time in deciding who that would be. It could be that, during this time, he was evaluating his sons, or it could simply be that he was still grieving the loss of his favorite and did not wish to replace him. In any case, it was not until 683 BCE that Sennacherib declared Esarhaddon, his youngest son, as heir.

His older brothers did not take the news well. In Esarhaddon's inscriptions he writes:

Of my older brothers, the younger brother was I

But by decree of [the gods] Ashur and Shamash, Bel and Nabu

My father exalted me, amid a gathering of my brothers:

He asked Shamash, “Is this my heir?”

And the gods answered, “He is your second self.”

And then my brothers went mad.

They drew their swords, godlessly, in the middle of Nineveh.

But Ashur, Shamash, Bel, Nabu, Ishtar,

All the gods looked with wrath on the deeds of these scoundrels,

Brought their strength to weakness and humbled them beneath me.

While his inscription tells the basic story, it is not the whole one. It appears that, after Sennacherib announced his choice, the brothers made clear their displeasure and Zakutu sent Esarhaddon into hiding. Exactly where he went is unknown, but it was somewhere in the region formerly held by the Mitanni. In c. 689 BCE Sennacherib had sacked and destroyed the city of Babylon, carrying off the statue of the great god Marduk, and this had not met with the approval of the Assyrian court or the people of the empire. Babylon and Assyria shared many of the same gods, and an affront to Marduk of Babylon was a sacrilege which could not be tolerated.

In 681 BCE Sennacherib was assassinated by two of his sons. While they certainly could have been motivated to kill him to take the throne (and so cut Esarhaddon off from his inheritance), they would have required some form of justification, and the destruction of Babylon would have served that purpose well. Their names are not known outside of the biblical versions given in II Kings 19 and Isaiah 37:38 where they are called Adrammelech and Sharezer. Following the assassination, the two princes fled Nineveh and sought refuge with the king of Urartu, Rusas II.

At this point Esarhaddon was re-called from exile (probably by his mother) and fought his brother's factions for the throne. After a six-week civil war, he emerged victorious, executed his brother's families, associates, and all who had joined their cause, and took the throne.

Reign & Restoration of Babylon

Among his first decrees was the restoration of Babylon. In his inscription he writes:

Great king, mighty monarch, lord of all, king of the land of Assur, ruler of Babylon, faithful shepherd, beloved of Marduk, lord of lords, dutiful leader, loved by Marduk's Consort Zurpanitum, humble, obedient, full of praise for their strength and awestruck from his earliest days in the presence of their divine greatness [am I, Esarhaddon]. When in the reign of an earlier king there were ill omens, the city offended its gods and was destroyed at their command. It was me, Esarhaddon, whom they chose to restore everything to its rightful place, to calm their anger, to assuage their wrath. You, Marduk, entrusted the protection of the land of Assur to me. The Gods of Babylon meanwhile told me to rebuild their shrines and renew the proper religious observances of their palace, Esagila. I called up all my workmen and conscripted all the people of Babylonia. I set them to work, digging up the ground and carrying the earth away in baskets. (Kerrigan, 34)

Esarhaddon carefully distanced himself from his father's reign and, especially, from the destruction of Babylon. Even though he identifies himself as the son of Sennacherib and grandson of Sargon II in other inscriptions, in order to make clear that he is the legitimate king, in his inscriptions concerning Babylon he is simply the king whom the gods have ordained to set things right. Sennacherib is only referenced as “an earlier king” in a former time. The propaganda worked, in that there is no record that he was associated in any way with the destruction of the city, only with the rebuilding. His inscriptions also claim that he personally participated in the restoration project. The historian Michael Kerrigan comments on this, writing:

Esarhaddon believed in leading from the front, taking a central role in what we nowadays call the `groundbreaking ceremony' for the new Esagila. Once the damaged temple had been demolished and its site fully cleared, he says, “I poured libations of the finest oil, honey, ghee, red wine, white wine, to instil respect and fear for the power of Marduk in the people. I myself picked up the first basket of earth, raised it on to my head, and carried it.” (35)

He rebuilt the entire city, from the temples to the temple complexes to the homes of the people and the streets and, to make sure everyone would remember their benefactor, inscribed the bricks and stones with his name. Scholar Susan Wise Bauer notes:

He wrote his own praises into the very roads underfoot: scores of the bricks that paved the approach to the great temple complex of Esagila were stamped, “For the god Marduk, Esarhaddon, king of the world, king of Assyria and Babylon, made the processional way of Esagila and Babylon shine with baked bricks from a ritually pure kiln. (401)

Although the prophecies concerning the rebuilding of Babylon had said that the city would not be restored for 70 years, Esarhaddon manipulated the priests to read the prophecy as eleven years. He did this by having them read the cuneiform number for 70 upside down so that it meant eleven, which was exactly the number of years he had planned for the restoration. Since he maintained a life-long interest in astrology and prophecy, it has seemed strange to some scholars that he would manipulate the priests in this way and discredit the integrity of the oracles. It seems, however, that he had a very clear vision for his reign and, even though he did believe in the signs from the gods, he was not going to allow that belief to stand in the way of achieving his objectives.

Military Campaigns

With Babylon restored, Esarhaddon set about expanding and improving upon his empire. The Cimmerians, a nomadic tribe of the north, were threatening his western borders, and the Kingdom of Urartu, which his grandfather had defeated in 714 BCE, had risen again in the north. His two brothers, who had killed their father, were still there under the protection of King Rusas II who, like the Urartu kings before him, had no love for the Assyrians.

In order to keep the Cimmerians at bay, Esarhaddon entered into a treaty with the Scythians, another nomadic tribe known for their skill in cavalry warfare. Although he felt he needed their help, he did not trust them as allies. Esarhaddon consulted his oracles regarding Urartu, the Cimmerians, and the Scythians, and his questions are preserved on divination tablets (prayers or requests inscribed on tablets which were then read in the temple in the presence of the god). Two of his tablets read:

Shamash, great lord, will Rusas, king of the Urartu, come with his armies, and the Cimmerians (or any of his allies), and wage war, kill, plunder, and loot?

Shamash, great lord, if I give one of my daughters in marriage to the king of the Scythians, will he speak words of good faith to me, true and honest words of peace? Will he keep my treaty and do whatever is pleasing to me?

While Esarhaddon was consulting the oracles, the Cimmerians invaded from the west in 679 BCE. By 676 BCE they had fought their way further into Assyrian-held lands and conquered Phrygia (in modern-day Turkey), destroying the cities and temples. Esarhaddon met the Cimmerians in battle at Cilicia and defeated them. He claims in his inscriptions to have killed their king, Teushpa, with his own sword.

At the same time the Cimmerians had invaded, the city of Sidon in the Levant rebelled against Assyrian rule and Esarhaddon marched down the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, defeated the rebel king, and executed him. He then turned about and marched against the allies of Urartu, the Mannaeans, to the north-east and, by early 673 BCE, was at war with Urartu itself. What happened to his brothers is unknown, but Urartu was again beaten back by the Assyrian army and, if the brothers were still alive when Esarhaddon defeated the Urartu, he would no doubt have had them executed.

The Egyptian Campaigns & Death

Having now secured his borders, Esarhaddon sought to expand them. Egypt had been a problem for the Assyrians in his father's reign and was still encouraging dissent and revolt in the Assyrian Empire. In 673 BCE Esarhaddon launched his first military campaign against Egypt and, thinking to storm Egypt in one furious push, marched his army at great speed. This proved to be a mistake. When they met the Egyptian forces under the Kushite Pharaoh Tirhakah outside the city of Ashkelon, the Assyrians were exhausted and quickly defeated. Esarhaddon withdrew from the field and his army limped back to Nineveh.

Esarhaddon learned from his mistake and, in 671 BCE, took his time and brought a much larger army slowly down through Assyrian territory and up to the Egyptian borders; then he ordered the attack. The Egyptian cities fell quickly to the Assyrians and Esarhaddon drove the army forward down the Nile Delta and captured the capital city of Memphis. Although Tirhakah escaped, Esarhaddon captured his son, wife, family, and most of the royal court and sent them, along with much of the population of Memphis, back to Assyria.

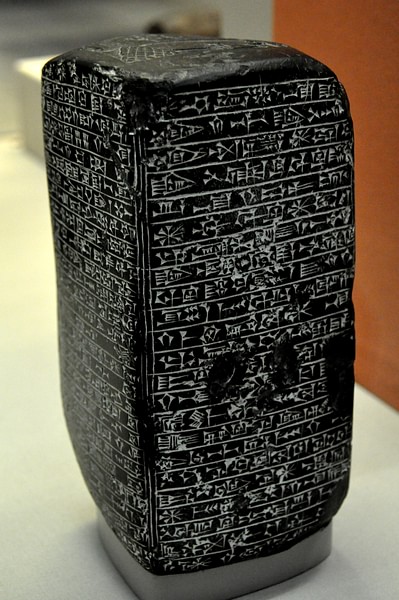

He then placed officials loyal to him in key posts to govern his new territory and returned to Nineveh. His victory is commemorated on his famous Victory Stele of 671 BCE now in the Pergamon Museum of Berlin, Germany. The stele depicts Esarhaddon in his full majesty, holding a war mace, with an attendant king kneeling at his feet and Tirhakah's son, also kneeling abjectly, with a rope around his neck.

His eldest son and heir, Sin-iddina-apla, had died in 672 BCE, and Esarhaddon now chose his second son, Ashurbanipal, as his successor. He forced his vassal states to swear loyalty in advance to Ashurbanipal in order to avoid any revolts over the future succession. At about this same time, Esarhaddon's mother Zakutu issued the Loyalty Treaty of Naqi'a-Zakutu (in either 670 or 668 BCE) which compelled the Assyrian court and those territories under Assyrian rule to accept and support the reign of Ashurbanipal. In order to avoid the kind of conflict he had gone through with his brothers, Esarhaddon also provided for his oldest son, Shamash-shum-ukin, by decreeing he should be king of Babylon.

Esarhaddon seems to have just finished setting his affairs in order when news reached him that Egypt had rebelled. Many of the trusted officials he had left in charge of cities and provinces had become sympathetic to Egyptian liberation and, no doubt, were profiting handsomely from their positions and were disinclined to send tribute back to Nineveh. In 669 BCE, Esarhaddon mobilized his army and marched again on Egypt. He had never been in the best of health throughout his reign and died of natural causes before he reached the borders. It would be left to Ashurbanipal to complete his father's work and conquer Egypt for the Assyrian Empire.