Etruscan pottery, produced over five centuries, was nothing if not varied. Indigenous wares such as the glossy black bucchero were made alongside red- and black-figure pottery imitating, yet modifying those produced in the Greek world. Geometric, floral, figure, and narrative decorations were appreciated and adapted from the Near East and Ionia, with even foreign potters and artists themselves settling in the cities of Etruria, such was the demand from the Etruscans for fine pottery for everyday use, at special banquets, and as offerings to their gods and dead. Pottery was also the material of choice for figure sculpture, best seen on the lids of large funerary urns, and as decoration for buildings in the form of statues and decorative plaques. Besides what they have left us of their own work, the Etruscans, great collectors of fine pottery that they were, have secured for posterity some of the finest Greek vases ever made and which now star in the collections of museums worldwide.

Villanovan Pottery

The Villanovan culture was a precursor to the more developed Etruscan civilization during the Iron Age in central Italy from c. 1000 to c. 750 BCE. In this period pottery was made by hand, not on the wheel, and used clay containing impurities of mica or stone which was fired at a low temperature producing relatively primitive wares. This type of pottery, known as impasto, was used to make bowls, storage jars, cooking pots, cups, and braziers. By the end of the 8th century BCE, potters had managed to improve the quality of impasto through long practice and refinement of technique.

Villanovan cemeteries contain burials of cremated remains in urns which are biconical (two vases with one smaller one acting as a lid for the other) and often carry simple incised decoration of geometric patterns, whirls, and swastikas, or even simple human 'stick' figures. Some urns have metal strips applied as decoration using lead or tin. One rarer type of urn, instead of a ceramic lid, has a bronze helmet on top with an impressive angular crest and embossed decoration.

Another common form where terracotta was used was the production of small models of houses, made to contain the ashes of the deceased. Perhaps imitating real architecture, these have decoration on the exterior walls of geometric patterns and an aperture above the door for releasing smoke. They also have roof decorations, probably imitating the terracotta additions which became so typical in later Etruscan architecture.

Red on White Wares

This type of pottery, originating from Phoenicia, was produced in Etruria from the end of the 8th century BCE and into the 7th century BCE, particularly at Cerveteri and Veii. The red-coloured vessels were often covered with a white slip and then decorated with red geometric or floral designs. Alternatively, white was used to create designs on the unpainted red background. Large storage vases with small handled lids are common of this type and then kraters which also have scenes such as sea battles and marching warriors.

Bucchero Wares

Largely replacing impasto wares from the 7th century BCE, bucchero was used for everyday purposes and as funerary and votive objects. It was preceded by an intermediary type known as buccheroid impasto. Turned on the wheel, this new type of pottery had a more even firing and, using the process of reducing the supply of oxygen in the kiln, gave a consistent and distinctive glossy dark grey to black finish (the clay's red ferric oxide being turned into black ferrous oxide).

The earliest known examples come from Cerveteri and date to c. 675 BCE. Bucchero was produced in many Etruscan centres (notably Cerveteri, Tarquinia, Veii, and Vulci) and has become a hallmark of Etruscan presence at archaeological sites in central and northern Italy. The Etruscans were Mediterranean-wide traders, too, and bucchero was thus exported beyond Italy to places far afield as Iberia, the Levant, and the Black Sea area.

Common shapes include bowls, single- and two-handled cups, amphorae, chalices, and jugs. More elaborate pieces have the addition of three-dimensional figures of both humans and animals. Bucchero votive and funerary offerings typically take the form of figurines and service trays (focolare) complete with bowls, plates, cups, and utensils. Decoration resembles that of metal vessels with added pieces and carving before firing to resemble embossed work. Some bucchero vases were covered in gold or silver leaf, sometimes also a thin layer of tin. Vessels are most often plain but can be decorated with simple lines, spirals, and dotted fans incised onto the surface. Red ochre was sometimes painted into these incisions. Patterns and simply rendered scenes from mythology could be applied to the pot before firing using a stamp.

Curiously, bucchero wares display the reverse trend of refinement seen in many other pottery type evolutions. The early period wares are finer with much thinner walls and more carefully made; these are known as sottile or fine (675-626 BCE). There is then an intermediary stage known as transizionale or transitional (625-575 BCE) before a final phase when wares are described as pesante or heavy (575-480 BCE). Finer wares are generally associated with the southern Etruscan cities and the heavier type with the northern. By the early 5th century BCE, bucchero was replaced by finer Etruscan pottery such as black- and red-figure wares.

Etrusco-Greek Wares

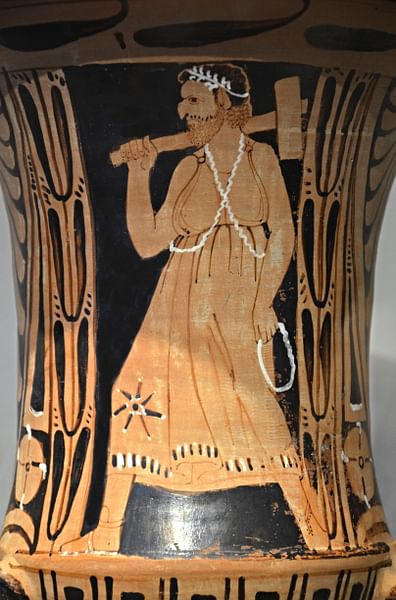

Between 670 and 600 BCE, many pottery vessels were imported from Corinth especially, Attica, Ionia, and the Near East. Popular imports from Phoenicia were the beak-spouted jug and the 'pilgrim flask,' a round flat bottle with geometric decoration. These imported goods, and sometimes the immigration of the artists themselves, inspired Etruscan artists to produce their own versions and to copy the new style of decoration in their own work. Plants, animal and human figures now replaced the rather austere geometric designs that had hitherto dominated. Wares were produced in such large quantities that art historians have been able to identify several distinct Etruscan pottery painters based on style and subjects. One such artist is the Micali Painter of Vulci who is credited with over 200 surviving vases. Scenes from Greek mythology are typical but with local additions and inventions. The large Caeretan hydria, a two-handled vase for holding water, was a speciality of Cerveteri.

In the 4th and 3rd century BCE there developed a trend of using column-krater vessels as funerary urns and these were often painted with two large heads facing each other, one male and one female. Although not portraits as such, they are more natural than similar depictions on Greek pottery. An inventive method to cheaply imitate metal wares was developed whereby pottery vessels were dipped into a basin of tin to give them a thin shiny coating which resembled silver, hence their name, ceramica argentata. Finally, and unique to the Faliscan region, mould-made standing heads of a goddess (perhaps Demeter) were manufactured and deposited as guardians in tombs.

Despite this varied home production, though, original Greek vases continued to be highly esteemed and frequently deposited in Etruscan tombs, one of the best sources of these wares outside Greece. As an example, the appropriately named Tomb of the Grecian Vases at Cerveteri had over 150 red- and black-figure pottery vessels from Attica deposited inside over several generations from 550 BCE onwards.

Terracotta Roof Decorations

One unusual field of pottery which became a particular Etruscan speciality was the creation of terracotta roof decorations. The idea went back to the Villanovan culture where the apex roofs of simple huts received such decoration. The Etruscans went one step further than similar decorations on Greek buildings and produced life-size figure sculpture to decorate the roofs of their temples. Private buildings also had terracotta decoration in the form of plants, palms, and figurines. The most impressive survivor from this field is the striding figure of Apollo from the c. 510 BCE Portonaccio Temple at Veii. The interior of this temple was further decorated with terracotta panels depicting scenes from mythology.

Terracotta panels were also used on the outside of buildings, too, usually on gable ends, and the format is best seen in 7th- and 6th-century BCE examples from Acquarossa. They show scenes of a dinner or drinking party with guests lounging on benches; musicians and dancers, including one acrobatically doing a cartwheel; and a procession of warriors carrying spears and shields accompanied by charioteers. The panels are currently on display in the National Etruscan Museum at Viterbo.

Sarcophagi & Funerary Urns

The Etruscans buried the cremated remains of the dead in funerary urns made of terracotta. During the 6th century BCE, there was also a trend of burying the body in decorative sarcophagi. Both types could feature a sculpted figure of the deceased on the lid and, in the case of sarcophagi, sometimes a couple. The most famous example of this latter type is the Sarcophagus of the Married Couple from Cerveteri, now in the Villa Giulia in Rome. The two figures recline on a couch or bed with the husband's right arm around the shoulders of his wife. Originally they would have held objects such as perfume bottles or eggs, symbols of regeneration.

Chiusi offers another interesting use of pottery. Early tombs there contained large terracotta vessels inside which were placed 'Canopic' jars containing the cremated remains of the deceased. The jars, typically half a metre in height, are made to resemble human figures, sometimes with a bronze mask attached, dressed in clothing, belts, and jewellery, and seated on miniature thrones of stone, bronze, or terracotta.

In the Hellenistic Period the funerary arts really took off, and figures, although rendered in similar poses to the 6th-century BCE sarcophagi versions, become less idealised and more realistic portrayals of the dead. They usually portray only one individual and were originally painted in bright colours. The sides of the lower box part are often decorated with relief sculpture depicting scenes from mythology or architectural motifs, for example, triglyphs and rosettes. The Sarcophagus of Seianti Thanunia Tlesnasa from Chiusi is an excellent example and is now in the British Museum in London.