Europa is a figure from Greek mythology who later gave her name to the continent of Europe. In one popular version of her story Europa was a Phoenician princess who was abducted by Zeus and whisked off to Crete; King Minos, he of the labyrinth and Minotaur fame, would be one of the results of Zeus' rape. The legend of Europa, and particularly the search for her by her three brothers, may well reflect the historical colonisation of the Mediterranean by the Phoenicians from 1200 to 800 BCE.

Abduction by Zeus

According to Hesiod in his Theogony, Europa is a daughter of Ocean and the Titan Tethys (357) while Homer's Iliad has her as the daughter of Phoenix (14:321). In another version of the story Europa is a Phoenician princess, the daughter of the Phoenician King of Tyre, Agenor, and Phoenix is her brother. This is the version of events presented by the 5th-century BCE historian Herodotus (1.2.1).

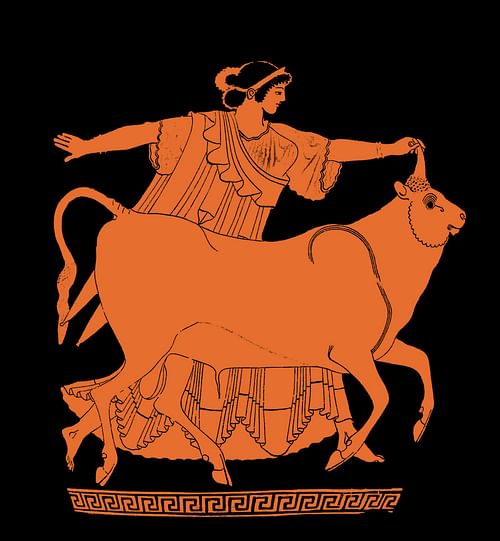

One day, while Europa was relaxing with friends by the seashore, the god Zeus spied her and immediately fell in love with her. In a somewhat bizarre courting strategy, Zeus either changed himself into a white bull or sent a handsome bull to woo the princess. Europa was indeed charmed by the docile animal and decorated him in flowers. Then, thinking she might ride such a gentle beast, she climbed on his back, which was when the bull swam with her into the sea, soared into the air and carried Europa far away from Phoenicia. Flying bulls perhaps not being the best of aerial transporters, it is not surprising that the bull swiftly fell into the sea and from there the pair swam to Crete. Once on the island, Zeus forced himself upon the princess, and the couple produced three children: Minos, the future king of Knossos, wise Rhadamanthys who would end up one of the judges of the Underworld, and, in a slightly later tradition, the great warrior and ally of Troy, Sarpedon. Although he was a frequent love-them-and-leave-them sort of god, Zeus did bestow upon Europa a few parting gifts. There was a hound who always got its quarry; a personal bodyguard, Talos the animated bronze man; and a javelin which always hit its target.

Meanwhile, when Agenor discovered his daughter's disappearance he sent his three sons off to find her again. These were Phoenix, Cilix, and Cadmus, and although they never did find their sister, the boys did found (at least in myth) new colonies in Phoenicia, Cilicia, and Boeotian Thebes respectively and thus became the founding fathers of those peoples.

The story ends when Europa later found consolation in Asterius, the Cretan king whom she married and who adopted her sons with Zeus. Finally, the bull that Zeus created became the constellation Taurus. The Zeus myth may have a basis in historical events, perhaps representing an actual Bronze Age raiding party from Minoan or Mycenaean Crete which attacked Phoenician Tyre and took treasures back to the island or, alternatively, represents an early Hellenic attack on Crete. The search for Europa and consequent founding of colonies also likely reflects the historical reality of Phoenician colonisation in the wider Mediterranean between the 12th and 7th centuries BCE which is now attested by archaeological evidence.

Name & the Continent

The name Europa means 'broad-face' and probably refers to the full moon. Alternatively, if the word is split as eu-rope, then it means 'well-watered'. The ancient Greeks first applied the word Europa to the geographical area of central Greece and then the whole of Greece. By 500 BCE Europa signified the entire continent of Europe (although the Greeks were only really familiar with the areas around the Mediterranean) with Greece at its eastern extremity. The River Don, north of the Black Sea, was typically considered the border with Asia. Herodotus (4.45) mentions that the continent is known as Europe but admits the exact boundaries are unknown and that he could not discover why Europa was chosen as the name. Herodotus does note the curious fact that the Greeks applied three women's names to the three great land masses they knew of, Europe, Asia, and Libya.

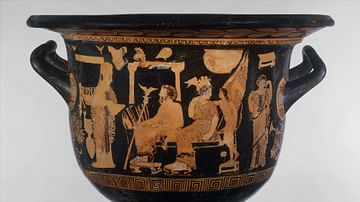

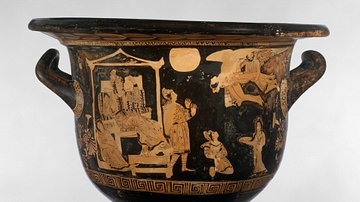

Representation in Art

Europa riding the bull of Zeus was a popular subject in Greek art from the 6th century BCE although the oldest known depiction, an amphora relief, dates to the century before. Metopes from the Sicyonian Treasury at Delphi (c. 560 BCE and in fragments) and Selinus (complete, 6th century BCE), a portion of frieze from the Temple of Athena at Athos and a relief slab from Pergamon all show the myth. Black-figure pottery and gems were other mediums where the Zeus-Europa myth was depicted, a very fine example of the former is an amphora by the Edinburgh painter now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. A full figure sculpture survives which is now in the Staatliche Museen of Berlin and which is a copy of a mid-5th-century BCE original. Europa is shrouded in a himation cloak, and a smaller statuette version inscribed with 'Europa' identifies the larger figure as the same subject. The theme of Europa and the bull was still popular with red-figure pottery painters in the 4th century BCE, especially in Attica and the south of Italy. The Romans continued to enjoy and perpetuate the myth and, even today, the subject remains a favourite and is shown on the reverse of the modern Greek two Euro coin.