The Faiyum (also given as Fayoum, Fayum, and Faiyum Oasis) was a region of ancient Egypt known for its fertility and the abundance of plant and animal life. Located 62 miles (100 kilometers) south of Memphis (modern Cairo), the Faiyum was once an arid desert basin which became a lush oasis when a branch of the Nile River silted up and diverted water to it. The basin filled, attracting wildlife and encouraging plant growth, which then drew human beings to the area at some point prior to c. 7200 BCE.

In the present day, Faiyum refers to the modern city of Medinet el-Faiyum but, in antiquity, designated the entire area which supported a number of large and quite prosperous villages and cities such as Shedet (better known as Crocodilopolis), Karanis, Hawara, and Kahun, among others. The name derives from the ancient Egyptian word Pa-yuum or Pa-yom meaning “the Lake” or “the Sea” and refers to Lake Moeris, created by Amenemhat I (c.1991-1962 BCE) of the 12th Dynasty during the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) when the kings of the 12th Dynasty, in particular, paid special attention to it.

The Middle Kingdom of ancient Egypt is considered a “golden age” in which the culture produced some of its finest works and the Faiyum benefited from the stable rule of the 12th Dynasty as much as any other region and, in many aspects, more so. Although some modern writers and commentators connect Pa-yom with the city of Pithom mentioned in the Book of Exodus 1:11, this claim is untenable; Pa-yom referenced an area, not a city, and the two words are not synonymous.

The region was most prosperous during the Middle Kingdom but declined after the fall of the New Kingdom (c. 1570-c.1069 BCE). It experienced a revival during the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 BCE) and the Roman Period (30 BCE-646 CE) after which it was neglected and declined steadily. It is best known today for the so-called Faiyum Portraits, a collection of beautifully rendered mummy masks created during these later periods and unearthed c.1898-1899 CE by the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie.

Early Habitation

Initially a lifeless basin, the Faiyum was transformed into a fertile garden by the natural silting of the Nile which diverted a significant branch of freshwater in its direction. The flow of the water carried with it the rich soil of the Nile River bed which settled in and around the newly-created lake and sprouted vegetation along its banks. The water and plant life attracted animals who made it their home and these then brought others in search of prey or simply creatures seeking water in an arid region.

This branch of the Nile would eventually be named Bahr Yusef (“Joseph's River”) in honor of the prophet Joseph in the Quran (the biblical counterpart of the Joseph from the Book of Genesis) and still exists in the present day as a canal. The first canal (known as Mer-Wer, “Great Canal”) was built during the Middle Kingdom. These developments came much later, however, after people arrived and felt the need to name objects and items around them; before it became a canal or had a name it was just a naturally occurring offshoot of the Nile. This waterway, and the fertile environment for wildlife it created, eventually drew human beings to the area.

Evidence of human habitation in the Sahara Desert region dates back to c. 8000 BCE and these people migrated toward the Nile River Valley. According to Egyptologist David P. Silverman, “traces of the earliest undisputed farming community in Egypt have been discovered at Merimde Beni Salama, a site on the western fringe of the Delta dating to c. 4750 BCE” (58). This date was accepted by the scholarly community for decades until, in 2007 CE, the ruins of an older farming community was discovered in the Faiyum dating to c. 5200 BCE and pottery has also been found dating to 5500 BCE. It should be noted that these dates relate only to established agrarian communities, not to human habitation of the Faiyum region which dates to c. 7200 BCE.

The Faiyum c. 5000 BCE was a lush paradise in which the people must have lived fairly comfortable lives. There was an abundance of food and water, shade from the sun through the tall fronds of many trees, and fish and wildlife to supplement their diet. At some point around 4000 BCE, however, a drought seems to have changed these ideal living conditions and many people migrated toward the Nile River Valley and left the Faiyum basin relatively deserted. These people would form the communities which grew into the great Egyptian cities of antiquity.

Peak Prosperity

In the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-c.2613 BCE) the region seems to have been largely neglected by these settlements, though it was still inhabited, but in the period of the Old Kingdom (c.2613-2181 BCE) the Faiyum was again a lush and wild paradise and became the preferred locale for hunting of wild animals by the Egyptian nobility. At this time, the Faiyum was known as Ta-She (“Land of the Lakes” or “Land of the Southern Lakes”) by the kings of Memphis who recorded their expeditions there.

It was a region primarily inhabited by wildlife (though there were still sporadic villages there) and numerous plants, including papyrus, grew in abundance. This was noted by the hunters who soon developed a system to harvest these plants for a number of different purposes. Papyrus is well known as the “paper” of ancient Egypt but was also used for making small fishing boats, rope, clothing, children's toys, amulets, baskets, mats, window shades, as a food source, and for many other items.

In the early Middle Kingdom, Amenemhat I ordered the construction of canal work along the Bahr Yusef which flooded the Faiyum and created the great Lake Moeris. This lake could be the one referenced in the New Kingdom literary work known as Setna II in which a great Egyptian sage defeats a Nubian sorcerer by transporting his diabolical creation to the center of a large lake. Amenemhat I's successor, Senusret I (c.1971-1926 BCE), seems to have felt the lake was too great a luxury and wasted prime agricultural land and so ordered a series of canals built to drain it.

Senusret I's canal system operated off a series of hydraulics which moved the water out of the Faiyum basin to other locales while still preserving a body of water there. The result was a reclamation of fertile land, the transport of water to areas in need of irrigation, and a continuation of the eco-system the lake sustained. Senusret I was succeeded by Amenemhat II (c.1929-1895 BCE) about whose reign little is known but this king's successor, Senusret II (c.1897-1878 BCE) continued Senusret I's policies in the Faiyum and maintained the canal system.

Senusret II was succeeded by his son Senusret III (c.1878-1860 BCE), considered the greatest king of the already impressive 12th Dynasty. Senusret III is best known for his successive victories over the Nubians and the redistricting of Egypt to cut the power of the district governors (nomarchs) but these achievements were only two aspects of a reign which epitomized the Egyptian cultural value of ma'at (harmony and balance) and elevated the Middle Kingdom to its greatest heights. Senusret III's reign marked the peak of prosperity for the Middle Kingdom generally and the Faiyum specifically.

Cities in the Faiyum, such as Kahun (founded by Senusret II) expanded and became more prosperous under Senusret III. The city of Shedet, which was the capital of Faiyum region from the Old Kingdom onward, also thrived as did the others. The rich produce of the region, which reportedly was better tasting than any other, resulted in a high demand and lucrative trade with other regions in Egypt and also abroad.

Senusret III's successor was Amenemhat III (c.1860-1815 BCE) who devoted significant attention to the region. He returned to the policies of Senusret I and installed retaining walls, dikes, and canals to lower the level of Lake Moeris further and provide more arable land. He built the famous Labyrinth as part of his temple complex at Hawara which Herodotus would later record as more impressive than any of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Amenemhat III also erected a number of other remarkable monuments throughout the area, as the kings of the 12th Dynasty had done before him, and instituted policies which stimulated the economy further and encouraged trade.

By this time, of course, the Faiyum was no longer roaming with wild animals or as lush with verdant plant life. As the region became more prosperous, it naturally became more popular; the villages grew into cities and the cities expanded and supported suburbs which grew up on their outskirts and expanded further. Building an addition to one's house, or erecting new homes, was as simple as measuring out a plot of land, making as many mud bricks as were required, and setting them in place. There were no zoning laws and one could build where one pleased as long as no one else objected.

There were upper-class homes which featured wooden beams, windows, and wooden doors but the simplest of homes could be constructed for a modest sum and relatively quickly. In the same way that people today ask friends and family to help them move or complete home improvements, those in the ancient Faiyum would host a party where guests would help them make and later assemble mud bricks to build a home or addition. The great wealth of the Faiyum, as well as its natural beauty, attracted more and more people to the region even though the tax the government levied on these citizens was higher than anywhere else in the area.

This was the state of the Faiyum region at the beginning of the 13th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom. The 13th dynasty lacked the power and focus of the 12th and slowly degenerated with each successive ruler. Towards the end, the nobility was focused far more on their own pleasure and personal dramas than the good of the country and allowed the Hyksos, a foreign people who had established themselves at Avaris in the Delta, to gain significant control over Lower Egypt. These developments led to the steady loss of power of the central government which finally fell, ushering in the era known as the Second Intermediate Period (c.1782-c.1570 BCE).

Little is recorded of the Faiyum during this time or in the New Kingdom which followed it. No new monuments were built and maintenance of the canals seems to have been neglected. By the beginning of the Ptolemaic Dynasty, the great canals, hydraulic works, walls, and monuments had suffered from years of inattention and the Faiyum was only a pale shadow of its former self.

The Greco-Roman Period & Faiyum Portraits

The Third Intermediate Period (c.1069-525 BCE), which followed the New Kingdom saw an Egypt divided in rule between Tanis and Thebes, rulers from Libya and Nubia, and was punctuated at the end by the Persian Invasion. The Late Period (525-332 BCE) was an era in which the country traded hands between the Persians and Egyptians until the Persians conquered the country. Alexander the Great took Egypt from the Persians in 332 BCE and, after his death, it was claimed by one of his generals, Ptolemy I Soter (323-285 BCE), who founded the Ptolemaic Dynasty.

Ptolemy I and his immediate successor, Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-246 BCE) devoted significant attention to the Faiyum, repairing and renovating the monuments, temples, canals, and administrative buildings which had fallen into decay. Ptolemy I drained Lake Moeris further for more arable land and Ptolemy II allocated lots of this fertile region to Greek and Macedonian veterans who improved upon it.

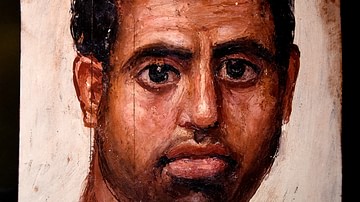

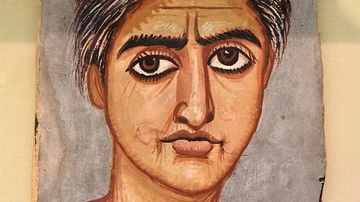

Since the conquest of Alexander the Great in 332 BCE, life in the Faiyum had improved dramatically. Although evidence of this prosperity is seen in a number of examples, the best and most famous is the Faiyum Portraits. These are paintings of the elite members of the community produced on wooden panels and placed on their mummies.

When they were first discovered by Flinders Petrie in the late 19th century CE it was thought they were painted from life and the subjects kept them on the walls of their homes until their deaths. It has since been established, however, that these paintings were done after the subjects' death. The incredible vitality of the paintings, especially the expressive eyes, makes it easy to understand why Flinders Petrie believed the subjects had to have been alive when the paintings were done.

These works are detailed renderings which accurately depict the clothing, jewelry, hair styles, and important personal objects of people at the time. The obvious wealth of the subjects reflects the prosperity of the region which is also exemplified simply by the existence of the paintings which are high-quality works created by an affluent and stable society. Egyptologist Helen Strudwick writes:

The Faiyum Portraits are truly original pieces of art, representing a synthesis of the naturalistic Classical style of portraiture with the ancient Egyptian concept of death as a gateway to a continuing existence in the afterlife. The portraits have provided Egyptologists with a wealth of information regarding high-status members of Greco-Roman society in Egypt – in particular their clothing, adornment, and physical characteristics – as well as being masterpieces of art in their own right. (336)

The paintings reflect the attention which was once again lavished on the Faiyum during this time. The first two rulers of the Ptolemaic Dynasty drew on inspiration from Egypt's past and worked to create a multi-cultural society which welcomed diversity and encouraged culture and intellectual pursuits. It was under these rulers that the Library at Alexandria, the Serapeum, and the great lighthouse at Alexandria were all created. Their successors were less competent however and, by the time of Cleopatra VII (c.69-30 BCE) the grandeur of Egypt had waned considerably.

Decline of the Faiyum

After Cleopatra's death, the country was annexed by Rome under Augustus Caesar (27 BCE-14 CE). By this time, after the years of neglect during the later Ptolemaic Dynasty, the Faiyum had deteriorated to the point where the canals and drainage pipes were blocked and unusable. Augustus ordered extensive repairs to the area on every level and brought the Faiyum back to life. Throughout the early years of the Roman Period the area experienced something of its former prosperity since it was still such fertile farm land and Egypt was considered Rome's breadbasket, furnishing the empire with grain.

The Faiyum continued to prosper as long as the empire was stable and expanding on a steady, regular, basis but, when it began to decline, its provinces followed suit. The Faiyum's population began declining in the 2nd century CE and a deadly plague devastated the population further. By the beginning of the 3rd century CE the population had been reduced to below 10 percent of the previous century's occupants.

The fertile valley, by this time, had been overused and much of the land had been developed to the point where there was no longer any wild game to hunt and no new wildlife came to the area. The papyrus plants, which had once been so plentiful, had been harvested to near extinction as had the flowers and other fauna which had once attracted the people to the region in the first place.

Although the Faiyum continued on throughout the Roman Period until the Arab Invasion of the 7th century CE, and served as the center of Egyptian resistance to the Arabs, it would never return to its former grandeur and prosperity. Under Arab rule it would certainly experience eras of abundant crops and prosperous trade, and the population again expanded, but the natural resources of the region had been depleted – and would continue to be as more and more was asked of the land – until the valley again resembled the arid basin it had been millennia before.

In the present day, the area is again a rich agricultural region due to ecological preservation efforts and improvements in land husbandry. A number of impressive ancient Egyptian ruins have also been preserved throughout the region, such as the pyramid of Amenemhat III at Hawara, but even though the area is relatively close to Cairo it does not receive many tourists. The people of the Faiyum today live largely as their ancestors did thousands of years ago as they farm the land with essentially the same kinds of tools, and in the same way, as the people did long ago in the golden age of the Middle Kingdom.