Ferdinand Magellan, or Fernão de Magalhães (c. 1480-1521), was a Portuguese mariner whose expedition was the first to circumnavigate the globe in 1519-22 in the service of Spain. Magellan was killed on the voyage in what is today the Philippines, and only 22 of the original 270 crew members made it back to Europe.

Discovering what became known as the Straits of Magellan in southern Patagonia and a passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, the voyage achieved its goal of showing that a route to Asia could be found by sailing west from Europe. The voyage was full of achievements, notable firsts, and a lifetime’s worth of new sights and experiences. There were also tremendous hardships and a major mutiny. The only ship of the original fleet of five to complete the voyage around the world was the Victoria, commanded by Juan Sebastian Elcano and packed full of precious spices. The round trip had taken three years and covered 60,000 miles. Not for nothing has this first circumnavigation been described as the greatest voyage of exploration ever undertaken.

Early Career

Ferdinand Magellan was born into a family of the minor Portuguese nobility in Villa Real in Tras os Montes around 1480. Ferdinand’s father was the sheriff of the port of Aveiro, and his mother was called Alda de Mesquita. Aged 12, Ferdinand was sent to Lisbon to become a page in the royal household, serving first the queen and then Manuel I of Portugal (r. 1495-1521). At court, Ferdinand received an excellent education which included mathematics, astronomy, and navigation.

Reaching maturity, Magellan served the Portuguese military in western India from 1505, and expeditions took him to Sofala and Kilwa in East Africa. In 1509 he participated in the war between the Portuguese and Gujarati-Egyptian alliance in Diu, western India. In 1510, Magellan assisted in the conquest of Portuguese Goa, and in 1511, Malacca in Malaysia. In 1513 he sailed home to Portugal and then served the Crown in the expeditionary force that attacked Azemmour in Morroco. It was here that he received a serious knee wound, which left him with a permanent limp.

The Portuguese & Spanish Empires

European explorers like Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) and Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) had been sent to find a maritime route from Europe to Asia in order to gain direct access to the immensely lucrative Eastern spice trade, find new agricultural lands, and possibly find Christian allies against the Islamic caliphates of the Middle East. Columbus’ route was blocked by the continent of America, but da Gama did round the Cape of Good Hope and cross the Indian Ocean to reach India in 1498. Portugal established colonies there such as Portuguese Cochin (1503) and Goa (1510). The source of many rare spices was in Indonesia, and a route was opened up by the Portuguese navigator Francisco Serrão, who sailed to the Spice Islands (aka the Maluku Islands or the Moluccas) in 1512.

The Spanish and Portuguese monarchies had audaciously carved up the entire world into two spheres of influence and prospective colonies in the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. Spain had the Americas and Portugal the coasts of Africa (and then India and East Asia). It was not important to these two royal houses that people already lived in these places or that a highly successful trade network had long been established there. The two kings were not entirely in agreement as to where each other’s empires ended and began, largely because neither had really started building an empire yet in physical terms. By 1518, though, things had moved along, and Portugal was making an excellent job of creating a string of trade entrepôts from Africa to Asia.

Charles I did not wish to be left behind, certainly not now that he was about to become Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556). Charles hoped to prove that the lucrative Spice Islands were in his half of the world - everyone's geographical knowledge of where exactly these islands were was a little shaky at this point in history. There were even rumours that some Portuguese cartographers were deliberately misplacing the islands in Portugal’s half. Further, Charles could bolster his claim no end if he gained access to the archipelago from the east (via South America and across the Pacific), that is through the Spanish half of the world. Ferdinand Magellan, after corresponding with various fellow mariners like Serrão and with the support of expert cartographers and astronomers like Ruy Faleiro, provided the king with a convincing plan to do just that. Magellan also brought with him extensive inside knowledge of Portugal’s empire and sea routes, effectively, state secrets. Charles formally accepted the proposal in March 1518. Magellan was made a commander of the Order of Santiago for good measure.

In addition to cutting out the Portuguese, a maritime route sailing west from Europe to Malaysia could perhaps save a great deal of time and hardship for ships rather than going via Africa. The seas and lands east of Malaysia were not then known to Europeans, but at least it had been understood that the trade winds of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans could be used to great advantage if caught in the right place at the right time. For this reason, the maritime route thought most likely to succeed was to sail from Europe across the Atlantic to South America, across the Pacific, and into East Asia, from there ships could stock up on spices and cross the Indian Ocean, round the Cape of Good Hope, and sail up the eastern Atlantic back to Europe. This is the route Magellan proposed to the Holy Roman Emperor. Nobody had ever done it, and nobody had ever circumnavigated the globe. The Pacific Ocean had only been sighted by a European in 1513 when Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1475-1519) crossed the Isthmus of Panama. No European knew its currents, its potential for storms, or how long it might take to cross it. The risks for Magellan and his crews were high and the hardships certain. The potential gains were enormous, with Magellan himself promised a percentage of the lands and wealth he claimed for the Spanish Crown.

Magellan’s Fleet

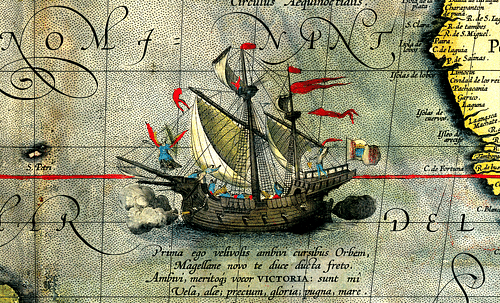

Magellan was given command of a five-ship fleet with the rather grand name of the Armada de Molucca. It was one of the best-equipped expeditions of the Age of Exploration. Magellan’s flagship was the 100-ton Trinidad. There was the San Antonio (120 tons), Concepción (90 tons), Victoria (85 tons), and Santiago (75 tons). All the ships were three-masted and carried the latest lateen sails. Both Magellan and Faleiro were given the titles of captain, a usual precaution in case something happened to Magellan. Another layer of authority was Juan de Cartagena, who was appointed by Charles as inspector general to oversee all financial matters and, perhaps, too, to make sure the two Portuguese captains remained loyal to the Spanish Crown. As it turned out, Faleiro’s mental instability led to him being dismissed from the expedition. Fortunately for Magellan, he retained all of Faleiro’s invaluable charts and navigational instruments. Unfortunately for the future of the expedition, this meant that Cartagena saw himself as co-leader. Cartagena did have vague authority from Charles, he was the highest-paid member of the expedition, and he was captain of the San Antonio, but Magellan was in no doubt that he was the admiral of the five-ship fleet. To make matters worse, the Spanish captains of Victoria (Luis de Mendoza) and Concepción (Gaspar de Quesada) considered themselves superior to their Portuguese leader.

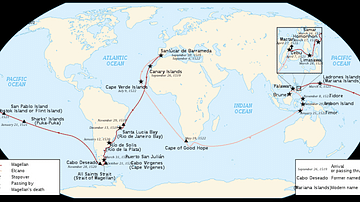

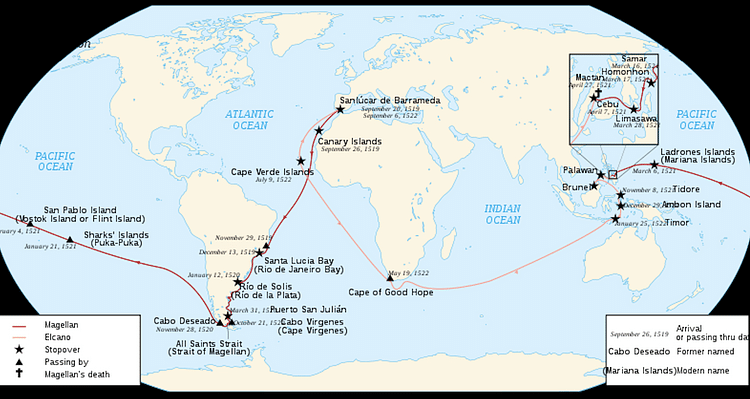

The Portuguese explorer left Seville on 10 August 1519 with a multinational crew of 260-70 men who came from across Europe. The fleet of ships landed and restocked at the Canary Islands, leaving on 3 October. It was here that Magellan received news that two Portuguese fleets were in hot pursuit, determined not to allow Spain access to their secretive empire in the east. Magellan sailed past the Cape Verde islands and down the coast of West Africa. The logbook of the expedition has not survived, but there is a detailed account by one of its participants, the Venetian scholar and diplomat Antonio Pigafetta, who had been given the task by Magellan of recording all aspects of the expedition for posterity.

First Mutiny

This was a stormy and difficult stretch, and many of the captains and crew wondered why they were not taking the more usual route of directly crossing the Atlantic. Their admiral was attempting to evade his Portuguese pursuers. As the ships battered their way to the equator and then found themselves becalmed, food rations were reduced. Cartagena, in particular, was already showing signs of disrespect for Magellan and refusing to address him with his proper titles. As the winds abandoned the fleet, Cartagena refused to take any orders from Magellan and threatened to stab him. Magellan responded by putting the inspector general in the stocks. This was a fate reserved only for common sailors, and both de Mendoza and de Quesada, the other two Spanish captains, successfully pleaded for Cartagena’s release. Instead, Cartagena was confined to the Victoria, and Antonio de Coca was given command of the San Antonio.

In November, favourable winds, at last, swept the ships across the Atlantic, then called the Ocean Sea. They intended to land at Rio de Janeiro, but the South Equatorial Current took them to Cape Saint Augustine. They restocked the ships and then followed the coast to arrive at the ‘River of January’ in mid-December 1519. Although claimed as part of the Portuguese Empire, there were as yet no permanent colonial settlements in Brazil and, more importantly for Magellan, no Portuguese ships in the harbour of Rio. It was here that Magellan carried out sentence on a crewman found guilty of sodomy, the penalty being death by strangulation. This was a normal maritime occurrence, which some captains ignored and others punished to the letter of the law, but it, nevertheless, fuelled resentment of Magellan from the ordinary men. To make matters worse, the cabin boy who had been the elder man’s partner threw himself overboard. Then Magellan added one more man to his ever-growing list of enemies. Antonio de Coca was replaced by Alvaro de Mesquita as captain of the San Antonio. De Mesquita was not particularly qualified except that he was Magellan’s cousin, a point noted with some bitterness by de Coca and the other Spanish captains.

The fleet departed Rio on 27 December and sailed down the long and unfamiliar coast of South America. The men settled down for another tortuous spell at sea, a situation whose discomforts are here summarised by the historian L. Bergreen:

At sea, sleep became the ultimate luxury, a solace impossible to come by…Hammocks had yet to be introduced on board ships…The men never became accustomed to the foul odors brewing aboard their ships…Pests were ubiquitous, an inescapable fact of life at sea…Rats and mice infested every ship…the men of the Armada de Molucca were plagued with all manner of lice, bedbugs and cockroaches. When conditions turned hot and humid, the insects infested the clothing, the sails, the food supply, and even the rigging. (106)

In January, the River Plate was explored, just in case this emergence of two rivers might provide a route to the Pacific Ocean. In February, after finding the inland waters too shallow, the fleet sailed on southwards. Magellan had the ships lower anchor at night so that no possible straits were missed in the darkness. Storms raged. The ships backtracked now and then to make sure of the geography. Strange animals were spotted like sea lions or sea elephants, described as ‘sea wolves’ by Pigafetta; several were killed for the fresh meat. The waters were now noticeably colder and a steelier blue, but the explorers were no nearer to discovering the end of the continent.

Second Mutiny

On 31 March 1520, eight months into the voyage and with the summer season ending, Magellan stopped at San Julián Bay in southern Argentina. The ships stocked up on fresh meat and fish, but other stores had to be rationed for the winter, an unpopular move with the men. Many of the crew no longer believed their leader that a strait to the Pacific existed. The Spanish captains were again conspiring for a takeover of the expedition, and this time they went so far as to take over the San Antonio, Concepción, and Victoria. The Santiago remained neutral while Magellan, already prepared, awaited developments on the Trinidad. In the first days of April, the action began. The mutineers sent word by longboat to Magellan that they were in control of the three ships and intended to sail back to Spain. Seizing the longboat, Magellan pretended to send a party of men to discuss terms on the Victoria. This party stabbed the Victoria’s captain and took over the ship. The Santiago, now loyal to Magellan, positioned itself alongside the Victoria and Trinidad with all three ships blocking the two mutineer-controlled vessels. Magellan then sent a man under the cover of darkness to cut the anchor of the Concepción. As the Concepción drifted closer, the Trinidad fired its cannons, and the Victoria attacked from the opposite side. The ship was boarded and the mutineers apprehended. The San Antonio surrendered, and Magellan was back in control of his fleet.

Luis de Mendoza, the leader of the mutiny had been killed in the action, but Magellan had the corpse ripped into four pieces anyway. A two-week investigation and trial found 40 of the expedition guilty of treason, and they were sentenced to death. Two men were tortured, and Gaspar de Quesada was beheaded. The rest had their sentence commuted to hard labour - Magellan did, after all, need these men to crew the fleet. The whole point of this trial was to reestablish Magellan’s authority and remind the men that, as on any other expedition at sea, they had good cause to fear their captain more than anything nature could throw at them. The strategy was effective except on Cartagena who, incredibly, still conspired to organize a mutiny, this time with the priest Pedro Sánchez. Both men would be marooned at San Julián Bay as the fleet sailed on. In the meantime, Magellan had all his ships overhauled ready for the next stage of the voyage, most of the dirty work being done by the men convicted of hard labour.

It was now that Magellan discovered that the stores loaded in the Canary Islands were only a third of what they should have been. It was now or never and at the beginning of May, the Santiago was sent on ahead to find the straits to the Pacific Ocean. Unfortunately, the lone ship met the worst storm of the voyage and was wrecked on the rocky shores. The surviving crew made the arduous trek back to the fleet which now awaited spring and calmer weather. Peaceful contact (at first) was made with the Tehuelche Indians who lived in the area. As these peoples wore elaborate boots, Magellan called them ‘big feet’ or patacones, and the region became known as Patagonia. On 24 August the fleet sailed south.

The Straits of Magellan

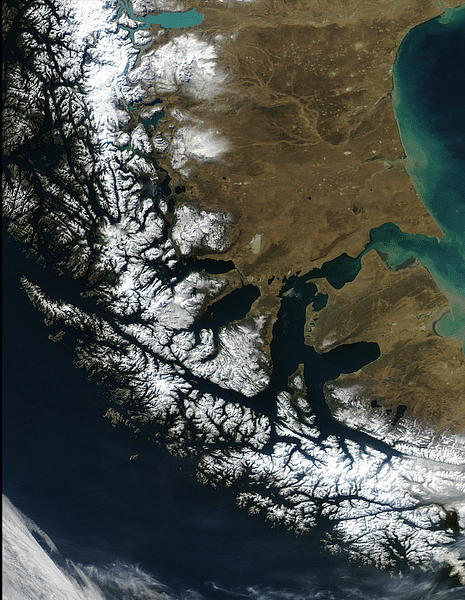

More storms swept the southern Atlantic, and Magellan was obliged to land for six weeks and await calmer weather. In mid-October, he set off yet again. The foul weather continued but, at last, the landscape changed, fragmented, and formed into what seemed to be a cape. There, leading westwards was a strait.

Magellan sailed through the straits of southern Patagonia which would ever-after bear his name between 21 October and 28 November. The straits were as difficult to navigate as they had been to find. High tides, strong currents, and a mix of great depths and lethal shallows clogged up with seaweed all conspired to present a formidable obstacle. The region seemed to constantly attract storms, too, as fierce and unpredictable winds sped in from the two converging oceans. The landscape was awe-inspiring with snow-topped mountains and huge glaciers, but it was the peculiar fires at night which captured the sailors' imaginations. Most likely, these fires were caused by lightning strikes, although the ever-suspicious mariners thought they were natives waiting to attack the ships. Consequently, Magellan called this land Tierra del Fuego or ‘Land of Fire’. It seemed a magical land inhabited by strange beasts like sea elephants and giant condors. Truly, this was the end of the world, but the stars remained familiar, and these, no doubt, reassured Magellan that he was on the right course to finally arrive at the Spice Islands. What the captain did not realise was just how far across the Pacific his goal really was.

Crossing the Pacific

During the difficult 38-day crossing of the straits, there had been another mutiny, this time a peaceful one, and in November the San Antonio returned home via the Atlantic Ocean (the ship arrived in Seville on 21 May 1521), and the crew set about blackening Magellan’s name with the authorities. They were subsequently absolved of any blame for returning home early). This was a serious blow to the expedition as the San Antonio had a significant proportion of the entire fleet’s stores.

The fleet of three ships sailed into the Pacific Ocean on 28 November 1520. They turned north and headed up the coast of Chile. On December 18, roughly opposite what is today Santiago, the ships turned westwards. To everyone’s astonishment, the ships now made excellent progress across an unbelievably calm sea and with a strong and steady wind at their backs. The explorers had hit the trade winds. No land was spotted as the ships missed islands like Tahiti and Bikini. This might have been providential since coral reefs and 16th-century ships would not have made good maritime companions. However, the lack of fresh food and water was significant. The stores of the ships turned putrid in the tropical heat. Scurvy now appeared and relentlessly claimed its victims. Magellan and the officers were unaffected as 30 men died of the disease and countless more suffered its horrors. The reason was the officers were served quince jelly on their superior dinner tables. Unbeknown to everyone, quince was a potent source of vitamin C, the deficiency of which causes scurvy.

No storms came as they crossed the Pacific, and the first land sighted was an island they called San Pablo, seen on 24 January 1521. On 4 February, Micronesia was reached, but they could not land on an island because of their protective reefs. Magellan was exasperated. Where were the Spice Islands, or indeed any large landmass? The Portuguese explorer threw his charts into the sea in frustration. Then, on 6 March, they reached the island of Guam in the Marianas group. The explorers had taken 98 days to cross the Pacific and sailed 7,000 miles. It was the longest unbroken sea voyage then recorded. The inhabitants of Guam welcomed the Europeans and revived them with fresh food and water. Unfortunately for Magellan, this island paradise was still thousands of miles from his goal. Also, unfortunately, and not untypically, the initially friendly relations between indigenous peoples and Europeans soon descended into violence following misunderstandings over the exchange of goods and what was considered private property.

Sailing on, the fleet reached what is today the Philippine Islands on 7 April. Once again the Europeans were welcomed and fed by the island’s inhabitants. Making his way through the Philippines, Magellan stopped at Cebu. Once again, the Europeans met hospitality and refreshment. It was here, on Cebu and the very brink of success, that Magellan was killed on 27 April 1521. The Portuguese mariner was first hit by a poisoned arrow and then butchered by a mob when he unwisely interceded in the battle of Mactan between rival chiefs.

The fleet and their devastated crews sailed on, certainly, they could not go back the way they had come. Juan del Cano (aka Juan Sebastian Elcano) was nominated the new leader of the expedition. In May, the Concepción was burned; the ship’s hull was riddled with worms, and there were simply not enough men left to sail three ships anyway. The fleet was down to two ships and a reshuffle of personnel led to the pilot João Lopes Carvalho being voted the new overall leader.

In July they reached Brunei and experienced such wonders as East Asian sailing junks, elephants, and rice wine. Alas, much to their impatience, the ships were leaking badly, and there was nothing for it but to stop at Cimbonbon in the Philipines for 42 days to overhaul them. On 27 September they set sail again. On 8 November 1521, first alerted by the smell of cloves and cinnamon that drifted across the sea, they finally reached Tidore in the volcanic Spice Islands group. Magellan had been right. There was a route from west to east. Within days, the ships were filled with spices, traded for rolls of cloth, simple glass cups, caps, bells, and metal tools like hatchets, knives, and scissors brought around the world for that purpose.

On 21 December, the spice-laden Victoria, commanded by Elcano, sailed on westwards while vital repairs had to be made to the Trinidad, which was again leaking badly. The Victoria sailed to Timor in Indonesia, and from there to the Cape of Good Hope, which took several attempts to round. They then sailed up the coast of Africa and landed at the Cape Verde islands in July where the men were surprised to find out they were a day behind in their meticulous records. The circumnavigators were the first to demonstrate that going around the world from east to west added 24 hours to one’s journey. After sailing the 10,000 miles from the Spice Islands and dodging ships with orders from the Portuguese king to apprehend them, the Victoria finally reached Spain on 6 September 1522. Only 18 men had survived from the 60 who had left the Spice Islands. The 18 circumnavigators had sailed an incredible 60,000 miles. The Spanish king and the backers of Magellan’s improbable expedition did extremely well out of the cargo of spices the Victoria had brought back.

Meanwhile, on 6 April, the Trinidad finally left the Spice Islands with a fortune - some 50 tons - of spices. Unfortunately, the captain was Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa, and he lacked the skills required to sail the ship safely home. Veering wildly off course and with his men dying from scurvy, de Espinosa was obliged, after seven months at sea, to return to the Spice Islands. The Trinidad was then captured by a Portuguese fleet sent to pursue Magellan. In October 1522, the Trinidad was smashed to pieces in a storm while at anchor. Magellan’s flagship - and more importantly for posterity, his logbook - were lost. The captured crew were left to rot in a Portuguese fortress on Ternate, one of the Spice Islands. Only four of these men made it back to Europe and so, of the perhaps 270 original expedition members who had left Spain over three years before, only 22 ever came home.

Legacy

Magellan had proved not only that South America could be rounded and that ships could sail around the globe on a western sea route, but also that trade winds and currents in the Pacific could be used just as they were closer to home to a ship’s advantage. It had also been shown that the Pacific Ocean was huge - the world was 7,000 miles further around than cartographers had thought. As the historian L. Bergreen puts it, "In terms of prestige and political might, the achievement was the Renaissance equivalent of winning the space race" (391).

The Straits of Magellan were not an easy route, nor were they a speedy one, and many subsequent mariners failed to find their proper entrance in the maze of islands at the southern tip of the Americas. Some explorers even claimed the Straits no longer existed and a landfall must have blocked the route, such was the difficulty in navigating these islands. On top of that, the ferocious storms that gathered around Cape Horn were another formidable challenge. Between 1577 and 1580 the English navigator Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596 CE) did find his way through the straits on his own circumnavigation of the globe, for the first time attacking Spanish colonies on the western coast of the Americas and plundering Spanish ships for loot.

Charles V used Magellan’s voyage to support Spain’s claim over the Spice Islands and followed it up with an armed fleet. Portugal and Spain again tried to thrash out a division of the world and Portugal ended up paying Spain a large quantity of gold to maintain control of the Spice Islands. As it turned out, Magellan had been wrong: the islands had been in the Portuguese half of the world as they saw it.

Finally, the great navigator’s name lives on in the very stars which were so important to his crossing the unknown seas. The two dwarf galaxies he spotted in the South Pacific are now called the Magellan Clouds.