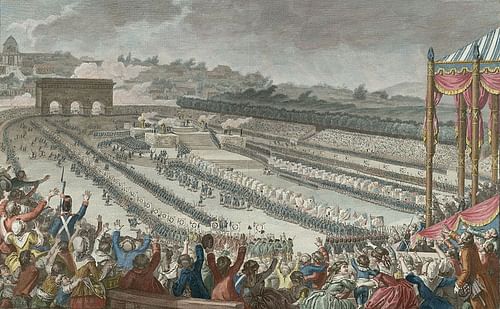

The Festival of the Federation (Fête de la Fédération) was a celebration that occurred on the Champ de Mars outside Paris on 14 July 1790, the first anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille. With over 300,000 people in attendance, the event honored the achievements of the French Revolution (1789-99) and the unity of the French people.

The festival itself was a monumental accomplishment, as tens of thousands of French citizens volunteered to labor in the mud and rain to build an amphitheater on the Champ de Mars with a colossal Altar of the Fatherland at its center. The event marked the birth of French patriotism, at least in the sense that such a term is understood today, and was the first celebration of 14 July, France's national holiday, which is still annually celebrated. At the same time, the festival was perhaps the high watermark of unity during the French Revolution itself, since afterward the revolutionaries devolved into factionalism and politics based on terror.

Unifying a Nation

By 1790, France was a nation intoxicated with revolutionary fervor, just as the French had begun to discover their national fraternity. The National Assembly, the representative body that had risen in defiance of the king during the Estates-General of 1789, had already declared the abolition of feudalism and noble tax privileges in the August Decrees and had proclaimed the natural rights of men in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. It was a new day in France, one in which all citizens could stand beside their neighbors as equals, at least in theory if not quite in practice. The feasts of the federations that sprang up across the country and culminated in the ecstatic, massive festival on the Champ de Mars celebrated not only the Revolution but also this sense of unity that had not existed in France under the Ancien Régime.

Prior to the Revolution, Ancien Régime France was a collection of regions that differed from one another in their customs, languages, and sets of laws. Partially owing to their origins as feudal domains that had little in common besides fealty to the same king, some French territories still valued their own local identities above that of the collective nation. Scholar William Doyle uses the example of Brittany where, even on the eve of the Revolution, people were more likely to speak Breton than French and dressed in traditional garments. In some areas, especially in the north, laws were customary, with over 300 local customs being observed. This differed from the south, which largely followed Roman law. As Doyle points out, this could lead to much confusion, as "the law relating to marriage, inheritance, and tenure of property could differ in important respects from one district to another; and those who held property in several might hold it on widely differing terms" (4). Even royal edicts could be contested by certain local parlements, the high judicial courts, which could refuse to register them within their jurisdictions. Other barriers to unity under the Ancien Régime included poor infrastructure outside metropolitan areas like Paris, hindering the flow of information, as well as taxation which also varied from place to place; the whole French landscape was pockmarked with internal customs barriers, set at multiple different rates on a wide range of items. Even currency and units of measurement differed, enough to make any foreign traveler mad with frustration.

But aside from merely upsetting 18th-century tourists, these differences frustrated any kind of national cohesiveness. Historical grievances and feuds between provinces worsened the issue. To some, unity of any kind seemed impossible; to emulate these feelings, French historian Jules Michelet writes:

How will Languedoc ever consent to cease to be Languedoc, an interior empire governed by its own laws? How will ancient Toulouse descend from her capital, her royalty in the south? And do you believe that Brittany will ever give way to France?...you will sooner see the rocks of Saint-Malo and Penmarch change their nature and become soft. (441)

Yet, the Revolution had done the impossible and given hope to France's 27 million people. By spring 1790, King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) had reluctantly consented to the Revolution's radical reforms and was living as a virtual prisoner in Paris. Down the street from him, the Assembly was working to codify their progress in a new constitution. And all across the country, common people had joined in the Revolution, as exemplified in the Great Fear of July 1789, when countryside peasants stormed the châteaux of their seigneurial lords. By 1790, many in France believed the Revolution to be over and looked to one another with a new sense of fraternity, united in their devotion to the patrie (fatherland).

This unity manifested itself in the form of liberty trees, which sprouted on village greens throughout France. These trees, trimmed of their leaves and branches, were decorated with ribbons of blue, white, and red, the colors of the Revolution and of the patrie. As trees had long symbolized fertility and rebirth, so too had these villages been reborn from the oppression of the Ancien Régime. They were a way for a village to show solidarity with the Revolution, and to tell the world that it "was no longer seigneurial property, and its people no longer dependents" (Schama, 492). Across France, public officials would be sworn in beneath liberty trees, priests would bless them, and joyful citizens would dance around them with hands clasped, entirely devoted to the nation. To paraphrase French socialist historian Jean Jaurès (1859-1914), French liberty, which previously had rested solely with the fortunes of the National Assembly, was now being concentrated in as many centers as there were communes (Furet, 65). Yet the federation movement that would soon sweep France would not be spearheaded by the Assembly or the villages, but by detachments of the National Guard.

Fraternity of the Guard

The National Guard had been formed in Paris in the wake of the Storming of the Bastille. A bourgeois citizens' militia, it had been created with the intention of keeping the city safe from royal soldiers and other enemies of the Revolution. Upon being given command, Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834) had put it to work keeping order in the streets of Paris and upholding the law. The Paris National Guard had been vital in removing the royal family to Paris following the Women's March on Versailles and now served as the king's bodyguards and veritable jailors.

While the Paris National Guard was the largest and most powerful of France's citizens' militias, it was by no means the only one. Even before the Bastille fell, mounting chaos and uncertainty had caused other cities and towns to set up their own citizens' militias, under various names such as "civic guards" and "volunteers of the Third Estate" (Furet, 66). The Great Fear intensified this phenomenon as citizens rushed to arm themselves, and towns imposed hasty conscriptions for their own defenses. While these militias arose at around the same time, they rose under varying circumstances. Some were created in conjunction with local municipal governments and military garrisons, who supplied them with arms, and others sprung up in opposition to these institutions. Most of the men who made up these guards were well-off members of the Third Estate who met all the qualifications needed to be active, voting citizens.

As historian Simon Schama states, the federation movement led by these militias arose from "the revolutionary obsession with oath swearing" (502). Theatrical ceremonies were commonplace amongst the revolutionaries, who considered such acts to be as sacrosanct as the Revolution itself. The first major fraternal ceremony took place on 29 November 1789 along the river Rhône, where 12,000 National Guardsmen from the Dauphiné and the Vivarais swore that nothing would divide them in their goal to uphold the constitution, not even the river itself. On 20 March 1790, guards from Brittany and Anjou embraced one another and swore to put aside their historical rivalries. After all, they were no longer "Bretons or Angevins, but French and citizens of the same empire" (Schama, 503).

The largest ceremonies took place in Strasbourg and Lyon. In Strasbourg, 200 children were ritually adopted by the National Guard as the "future of the patrie", while fishermen dedicated the Rhine in the name of liberty (Shama, 503). In Lyon, the celebration lasted for two days, with over 50,000 people attending. The Lyon festival centered around a mighty statue of the goddess Libertas, who held a pike in one hand and the Phrygian cap in the other, a reference to the caps that ancient Romans had presented to freed slaves. The air above Lyon was filled with the sounds of cannons, music, and oath-taking; the attendees wore the tricolor sash of the Revolution above their traditional regional clothes, signifying their devotion to France above all else. In the words of Michelet, the federation movement had symbolized the "death of geography" within France; it was the "legitimate restoration of ancient relations between places and populations which the artificial institutions of despotism and fiscality have kept divided" (442).

Preparing the Altar

After all these massive and cathartic celebrations, it was only natural for one to be held in Paris, grander than the rest. Aside from merely celebrating fraternity, the National Assembly saw another reason why such an event might be appealing. The constitution was coming on a year in its development, with no end in sight (it would not be finished until September 1791). It was vital, therefore, for the Assembly to remind the people of the past year's accomplishments and to keep them anticipating the constitution's completion. To this end, the celebration was fittingly planned for 14 July 1790, the first anniversary of the Bastille. It was to be held on the Champ de Mars, which at the time was a large, open field reserved for military drills.

In charge of the planning were Jean Sylvain Bailly, mayor of Paris, and General Lafayette. Their idea was ambitious, yet incredibly grandiose. In keeping with the Revolution's love of all things Roman, the field was to be turned into a gigantic amphitheater, layered in 31 steps, and meant to accommodate 400,000 people. At the entrance, there was to be a huge, triple-arched triumphal arc on the opposite side of the field from a grand pavilion that would seat the king and the Assembly. In the center of all this, there was to be a massive Altar of the Fatherland, where the sacred oaths were to be taken. This plan was not approved by the Assembly until 21 June, however, leaving only three weeks for preparation.

It was a difficult project. The field was littered with huge rocks that had to be removed, and much of the land had to be dug up to accommodate the altar in the center. Heavy rains further disrupted this process, and sand and gravel had to be brought in to stabilize the ground. To complete this herculean labor in time, many hands were needed. Thanks to the spirit of fraternity that the federation movements brought to France, men and women flocked to the Champ de Mars in droves, volunteering their time and labor to turn the field into a shrine to the patrie.

These volunteers came from all walks of life; noblewomen worked alongside nuns, artisans beside beggars. Even Lafayette would arrive every day, roll up his sleeves, and pick up a shovel to labor for a few hours. Bands played to keep spirits high, actors performed for resting workers. The preparation for the festival was practically a festival itself, and the Champ de Mars was transformed into a stadium in time for the anniversary.

As part of the coming ceremony, every iteration of the National Guard throughout France had been asked to contribute 150 members each to represent their department. On the day of the celebration, there were 14,000 provincial guards in the city, bringing the total number of citizen soldiers present up to 50,000 when combined with Lafayette's own men. Additionally, tens of thousands of civilians poured in from across the nation.

The Festival

The day of celebration, 14 July 1790, was dark and gloomy and afflicted with heavy rainfall. Yet this did nothing to hinder the turnout. The Guardsmen assembled on the boulevard du Temple, alongside members of the Paris Commune (the city's revolutionary government). With the honor of holding the departmental banner falling to the eldest man in each regiment, the National Guard set off on their march through the city and toward the field. As they went, they were met with artillery salutes and joyful tunes from military bands. Crowds of civilians followed, dancing with one another and singing the revolutionary song, "Ça Ira" ("It'll be fine"). Together, the people of France made their way to the Champ de Mars, in defiance of the steady downpour.

Upon arriving, they were greeted by the sight of the magnificent Altar of the Fatherland, adorned in faux marble. On one side was this inscription:

All mortals are equal; it is not by birth but only by virtue that they are distinguished. In every state the Law must be universal and mortals whosoever they be are equal before it. (Scurr, 134)

On the opposite side were the three words that the people would soon swear oaths to:

The Nation, the Law, and the King:

the Nation, that is you;

the Law that is also you;

the King, he is the guardian of the Law. (Schama, 509).

Over 300,000 people attended the festival. The National Guardsmen marched past the king and queen, who were situated in a pavilion at one end of the field. Once the soldiers were in position, 200 priests climbed the steps of the altar, wearing the revolutionary sash. They were led by Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (1754-1838), the bishop of Autun, who would soon be excommunicated by the pope for his complicity with the Revolution. Talleyrand took his place on the altar beside Lafayette and reportedly whispered to the general, "Don't do anything to make me laugh," before blessing the regimental banners and performing mass (Unger, 266). "Sing and weep tears of joy," Talleyrand said to the people, "for on this day France has been made anew" (Schama, 511).

After mass, Lafayette re-entered the makeshift stadium on his famous white horse, dismounting before the king to ask permission to administer the oath. After receiving such, he climbed the steps of the altar and dramatically extended his arms toward the gathered throng of citizens. As his voice was inaudible above the storm, his words were simultaneously read aloud by soldiers amongst the crowd so that when he finished administering the oath to be faithful to the nation, the law, and the king, 350,000 voices answered him with: "Je le jure" ("I do so swear"). Afterwards, King Louis XVI himself stood up. Referring to himself by the constitutional monarchist title 'King of the French', he swore to uphold the decrees of the National Assembly. Then, Queen Marie Antoinette held up the young dauphin, who was dressed in the uniform of the National Guard, to thunderous applause.

There were more spectacles to be had. Outside the Notre Dame, a play was performed depicting the Storming of the Bastille. Back on the Champ de Mars, a small delegation of Americans entered after the oaths had been sworn. Led by John Paul Jones, they carried the stars and stripes, the first appearance of that flag on European soil. The Americans and French National Guards saluted one another, a show of solidarity from one liberated people to another. The day's celebrations culminated in a popular feast that continued for four days. On the last day, the 18th, there was a water spectacle on the Seine that included musical barges and jousts.

Aftermath & Legacy

The festival was certainly memorable and was largely considered a success. However, not everyone was happy. Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau (1749-1791), who personally detested Lafayette, believed that the general had sidelined the king and had used the event to prop up his own ego and that he would soon use his popularity to become a dictator. Journalist Camille Desmoulins concurred, mocking the ceremony and the king's pitiful subservience, but most people felt only the euphoria that came with such pure displays of brotherhood. One observer, the German writer Joachim Heinrich Campe, wrote: "How can I describe all those joyous faces lit up with pride? I wanted to fold in my arms the first persons I met…for all national differences had vanished, all prejudices disappeared" (Schama, 513).

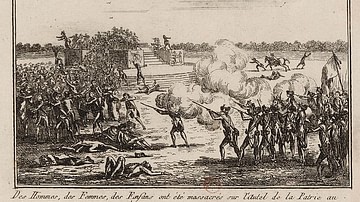

The festival was supposed to be an annual celebration. However, by the time the date rolled around the next year, the king's flight to Varennes had covered the Revolution in a dark cloud of uncertainty. A celebration was still held, but it was nowhere near as spectacular and was overshadowed by the Champ de Mars Massacre, which took place in the exact spot three days later. 14 July would not become an official holiday until 1880, after which it has been continually celebrated as France's national holiday, informally called Bastille Day. Most importantly, the Festival of the Federation marked the beginning of French national unity and the birth of French patriotism and symbolized the high point of the Revolution before the dark days of chaos, war, and terror.