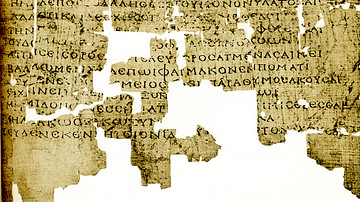

The Foundation Decree of Cyrene (c. 322 BCE) is a covenant between the citizens of Cyrene in North Africa in the 4th century BCE and those of their mother-state of Thera granting any who wish to become Cyrenean citizens the same rights and freedoms as those who settled the colony in 631 BCE.

The first part of the inscription gives the 4th-century BCE covenant while the second is a copy of the 7th-century BCE oath taken by the Therans who colonized Cyrene (modern-day Shahhat, Libya) under their leader Aristoteles who later took the throne name Battus and reigned as their first king c. 631 to c. 599 BCE.

The stele was discovered in the ruins of Cyrene in 1922, and the second half was at first considered a forgery. The entire inscription is now regarded by many scholars (though not all) as authentic as the second half is understood as a copy of the original 7th-century oath which seems to have been widely known. The story of the colonization of Cyrene in 631 BCE is told by both Pindar (l. c. 518 to c. 448/447 BCE) and Herodotus (l. c. 484-425/413 BCE), both of whom touch on the events of the original oath as given on the stele of the Foundation Decree.

Scholars continue to debate the meaning of the Foundation Decree with no clear consensus reached at present. Why it was issued, precisely when, and what it accomplished, are questions that remain unanswered. The stele is presently part of the permanent exhibit of the Cyrene Museum, Shahhat, Libya.

Founding & Battiad Dynasty

Cyrene was founded as a colony of Thera (modern-day Santorini) due to overpopulation on the island. The people consulted the Oracle at Delphi for an answer to their problems and were told to send an expedition to colonize North Africa. Herodotus provides the Theran version of how this happened:

King Grinnus of Thera was consulting the oracle on other matters when the oracle declared that he would found a community in Libya. "Lord," he replied, "I am already too old and weighed down to take off like that. Please give the job to one of these younger men here." As he was saying this, he waved in the direction of Battus. That was all that happened then, and later, after their return home, they took no account of the oracle. They did not know where Libya was, and they were not so foolhardy as to send a colonizing expedition off to some unknown destination.

For the next seven years, however, no rain fell on Thera, and all their trees, with a single exception, withered. The islanders consulted the oracle, and the Pythia reminded them that they were supposed to colonize Libya. Since they could not find a cure for their troubles, they sent messengers to Crete to find out if any their countrymen or resident aliens had ever gone to Libya.

(Book IV. 150-151)

The Cretans found them a merchant named Corobius who led them first to an island called Platea, then Asilis, and then the fertile region of Cyrene on the coast of North Africa. Prior to reaching Libya, when they were still at Platea, they sent word back to Thera of their success. Herodotus writes:

After they had left Corobius on the island, the reconnoitering party of Therans returned to Thera and announced that they had founded a settlement on an island off Libya. The Therans resolved to send one in every two brothers (which one went was to be decided by lot), to draw the men who went from every one of their seven districts, and to send Battus as the expedition leader and king of the future colony. (Book IV. 153)

This passage alludes to the 7th-century BCE oath given in the second part of the Foundation Decree of Cyrene.

Leaving Platea, then Asilis, they established themselves at the location which became Cyrene, allegedly named for a princess loved by Artemis and Apollo who had slain a lion at that spot without using weapons. Modern-day scholarship has determined the site was actually named after a local spring known as Cyre (Freeman, 192), but, in the 7th century BCE, the story of the princess who was taken by Apollo as his wife and became queen of the country (given in Pindar's Pythian Ode 9) was understood as truth.

The city was established with Battus as king and flourished under the early rulers of the Battiad Dynasty:

- Battus I – r. c. 631 to c. 599 BCE

- Arcesilas I – r. c. 599 to c. 583 BCE

- Battus II (the Prosperous) – r. c. 583 to c. 560 BCE

- Arcesilas II (the Harsh) – r. c. 560 to c. 550 BCE

- Battus III (the Lame) – r. c. 550 to c. 530 BCE

- Arcesilas III – r. c. 530 to c. 514 BCE

- Battus IV (the Fair) – r. c. 514 to c. 470 BCE

- Arcesilas IV – r. c. 470 to c. 440 BCE

Cyrene expanded under the first three kings, and, under Battus II, its prosperity encouraged an influx of colonists from the Peloponnese, Crete, and elsewhere in Greece. Cyrene became the first of the Pentapolis (five cities) of the region of Cyrenaica. The indigenous Libyans called on Apries, pharaoh of Egypt (r. 589-570 BCE) for help, and he sent an army which was decisively defeated by the Cyreneans. After he was deposed, his successor Amasis (r. 570-526 BCE) made peace with Cyrene and initiated trade that further enriched the city.

Under Arcesilas II, this prosperity declined due to infighting between him and his brothers, and this continued until his assassination c. 550 BCE when Battus III came to the throne and encouraged the change in the constitution, under the direction of the lawgiver Demonax, to decrease the power of the king and increase that of the people, essentially establishing a democracy.

The last three kings of the Battiad Dynasty did little beyond depleting resources, stirring up civil strife, and restoring the monarchy, which was again rejected in 460 BCE when Cyrene became a republic. The Battiad Dynasty ended with the assassination of Arcesilas IV and his son in 440 BCE. Cyrene's economy again prospered after the establishment of the republic, and it was this wealthy city the Therans back home were invited to participate in through the Foundation Decree of 322 BCE.

Thibron's Invasion & The Decree

When Persia took Egypt in 525 BCE, Cyrene came under Persian rule, and when Alexander the Great arrived in 332/331 BCE, he claimed Cyrene as part of his North Africa holdings with Egypt. After Alexander's death in 323 BCE, Egypt and Cyrene were controlled by his general Ptolemy I Soter (r. 323-282 BCE) who founded the Ptolemaic Dynasty.

In 322 BCE, Cyrene was invaded by forces under Thibron (d. 322 BCE), a renegade commander in Alexander's army who, in the chaos of the early Wars of the Diadochi (the conflict between Alexander's generals for control of his empire), murdered the governor of Babylon, stole the treasury, outfitted a fleet, and sailed for Cyrene which was famous for its wealth. When the monarchy of Cyrene was rejected in 460 BCE, a number of upper-class families went into exile, and their descendants (or later exiles unrelated to that event), seem to have encouraged Thibron's invasion.

Ptolemy I sent his general Ophellas (l. c. 350-308 BCE) to meet Thibron, who had already taken (and damaged) Apollonia, the vital port of Cyrene, and the city suffered further damage and loss of life in the battle between their forces. Ophellas defeated Thibron, who was executed, and became governor of Cyrene under the Ptolemies.

The Foundation Decree of Cyrene was drafted after these events, but scholars still debate its purpose and motivation. The simplest reason would seem to be a need to repopulate the city following Thibron's invasion, but this cannot be substantiated as the casualty count is unknown. It seems, however, that Cyrene was looking to replenish – or expand upon – its existing workforce, vital to the city's economic stability that relied primarily on agriculture and, specifically, the harvesting and cultivation of the plant silphium which was used as a medicine, as a seasoning and aromatic, and for other purposes.

Silphium, which only grew in the region of Cyrene, became their major export and contributed enormously to the city's wealth as its value rose around the Mediterranean. The plant was featured on the currency of Cyrene, notably during the reign of the king Magas (276-250 BCE) who succeeded Ophellas.

It is possible, however, that the Decree had nothing to do with silphium at all and was simply a promise to the citizens of the mother city that they would be welcomed with all rights and freedoms in Cyrene if they chose to come. Cyrene, in 322 BCE, was wealthier and far more prestigious than Thera, however, so unless they suddenly found themselves in need of a greater labor force, it is difficult to understand the purpose of the Decree.

Summary & Text

The inscription opens with the salutation to the god and wishes for good fortune, then notes how the decree was proposed by one Damis, son of Bathykles, presumed to be a Cyrenean. The first part then decrees that all Therans who choose to come to Cyrene will have the same rights as those already living there provided they take the same oath as the original colonists did in 631 BCE. The first section ends by noting that the expense of engraving the stele will be covered by the treasury of the temple of Apollo at Cyrene where it will be displayed.

The second section, as noted, is the oath of 631 BCE. It states how one son would be chosen from each family and all freemen were welcome to join the expedition. As colonization of non-Greek regions was dangerous (owing largely to the objections of those already living there), it is stipulated that, if the colony was "compelled by overwhelming necessity" to return within five years, all rights and property on Thera would be restored; while anyone who refused to sail when ordered to by the state would be executed and forfeit all rights and property. The oath ends with a curse on those who do not keep the oath.

The following translation is by Catherine Dobias-Lalou from Inscriptions of Greek Cyrenaica (referenced in the bibliography as Decree of Cyrene for the Citizenship of the Thereans, Therean 'decree' and founder's oath):

God. Good Fortune.

It was proposed by Damis son of Bathykles: about the proposal made on behalf of the Theraeans by Kleudamas son of Euthykles with a view to success and prosperity for the people of the Cyrenaeans, that is to say to give back city-rights to the Theraeans in accordance with the arrangements of our ancestors, both those who, coming from Thera, founded Cyrene and those who remained in Thera, since Apollo granted the Theraeans who founded Cyrene to live in prosperity if ever they would abide with the oaths taken with one another by our ancestors when (10) they dispatched the founding expedition following Apollo Archagetas' injunction; to the Good Fortune, may it seem good to the people: That the Theraeans should keep on equal civic rights also in Cyrene in the same terms; that all Theraeans living at Cyrene should take the same oath as the one taken once by the others; that they settle themselves into a tribe, a patra and (one amongst) the nine hetaireiai; that this decree should be engraved on a white marble stele and that the stele should be placed into the ancestral sanctuary of Apollo Pythios; that on the stele should also be engraved the oath that was taken by the founders when they landed in Libya (20) with Battos, arriving from Thera to Cyrene; as to the expense necessary for the stone or the engraving, those in charge of the accounts should provide it from Apollo's income.

Clauses of the oath of the founders

It seemed good to the assembly: whereas Apollo spontaneously declared that Battos and the Theraeans should settle the colony of Cyrene, the Theraeans consider it decided that Battos should be sent to Libya as chief of mission and king; that Theraeans should sail off as companions; that they should sail off on equal and same terms from each family, one son being chosen from each family; that would also be allowed to sail off all the other [citizens] of age and (30) among the rest of the Theraeans any free man [who would be willing]; that, if the settlers hold on the settlement, anyone amongst the Theraeans who would later on sail to Libya should take part in the [ civil rights] and honours and should receive by lot a portion of owner-free land; that if on the contrary they do not hold on the settlement and are not able to settle on the city but are compelled by overwhelming necessity, they should within five years fearless leave the country (and sail back) to Thera and their belongings and be full-right citizens; that anyone who would refuse to sail when the city wants to send him would be liable to death penalty and his belongings should be confiscated; that anyone who would shelter or conceal him, be it a father for his son or a brother for his brother, (40) should be liable to the same penalty as the rebel.

Such are the clauses on which they took oath, as well those who remained on the spot as those who were sailing off with the aim of settlement, and they uttered curses against who would transgress those clauses and would not abide to them, either amongst those settled in Libya or amongst those remaining on the spot. Having formed waxen figurines, they burnt them off, all together, men, women, boys and girls, while uttering these curses: "Whoever will not abide to the clauses of that oath, but will transgress them, should melt away and flow down like the figurines, himself, his offspring and his belongings. Whoever will abide to these clauses, either (50) one sailing off towards Libya or one [remaining] in Thera, should enjoy all sorts of prosperity for himself and his offspring."

Conclusion

It is assumed the content of the Decree was sent to Thera in some form, but this is hardly certain. It may be the Therans from the mother city had already arrived or the Decree may have been politically motivated for reasons that might never be known. Scholar Daniel Dalicsek comments:

The original decree's text suggests a close relationship between colonizers sent to Cyrene and the citizens remaining home in Thera. The inscription dates to the fourth century, when Cyrene was wealthier and more important than her mother city. The statement in this context appears rather patronizing, as the Cyrenians did not need the connection to the metropolis and were a polis in their own right. What they might have needed was workforce to support the economic growth, "in order that the city may prosper", and the obvious way to invite new inhabitants was to recruit them from the mother city and to grant them citizenship. (3-4)

Dalicsek also notes how "the inscription proposes several questions but informs us about the contact between a mother city and her colony centuries after the foundation" (4). This is an accurate assessment, but the questions have no answers. The Foundation Decree of Cyrene is one of those historical events that scholars may be sure took place but why it did, what motivated it, and what the results were are unknown. Even the date of c. 322 BCE for its issuance has been challenged.

If the Decree was issued because of the casualties of the Thibron invasion, and if it was answered by an influx of Therans to Cyrene, this might explain how Cyrene was able to rebound after the conflict and continue to supply the Mediterranean region with silphium and other crops – but only if it were certain that there was a significant loss of workers – and this, like almost every other aspect of the Foundation Decree, is not certain at all.