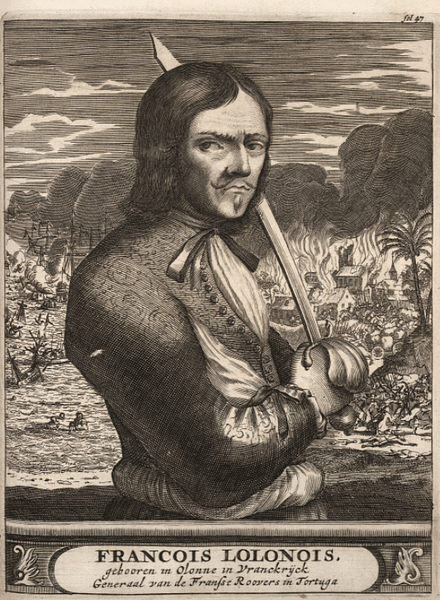

François L'Olonais (also spelt L'Olonnais or L'Ollonais, c. 1630-1668), real name Jean-David Nau, was a French buccaneer and pirate who operated from Tortuga on Hispaniola. In 1667, he famously attacked Venezuela, then part of the Spanish Main, and such was his reputation for sadistic cruelty, he was known as the 'Flail of the Spanish'. L'Olonais continued his rampage for plunder in the Bay of Honduras but was ultimately butchered and eaten by local cannibals.

Early Career

Jean-David Nau was born between 1630 and 1635 in Les Sables-d'Olonne on the west coast of France, hence his later nickname François L'Olonais. At the age of 20, he embarked on a life at sea and ended up in the Caribbean. Perhaps unimpressed with the harsh realities of life on a sailing ship, he became an indentured servant on a plantation. After serving for three years, Nau joined the wild band of hunters on Hispaniola who became known as buccaneers for their habit of smoking their meat on grills. The Spanish authorities tried repeatedly to repress the buccaneers, but they resisted these raids, often retreating to the wild interior of the island. Many buccaneers became pirates, and Nau was one of these, perhaps motivated above all by revenge on the Spanish who had killed so many of his brethren hunters.

Turn to Piracy

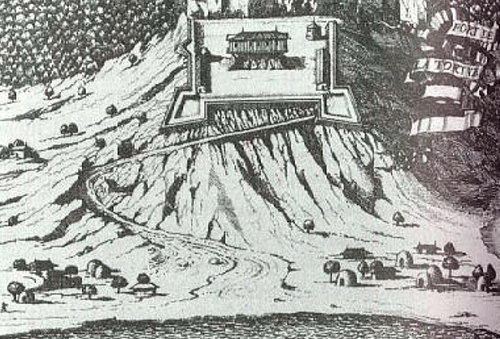

Tortuga (Ile de la Tortue), located in northwest Hispaniola (modern Haiti and the Dominican Republic) became a major buccaneer haven from the 1630s. The island received its name for its resemblance to a turtle when seen from afar. The French colonial authorities controlled Saint Domingue on the other side of the island and turned a blind eye to the buccaneers at Tortuga since they were a useful deterrent against attacks from Spanish warships. François L'Olonais began to use Tortuga as a base for his pirate activities from the 1660s. He was given a captured ship by the governor and encouraged to attack Spanish ships.

The Cruellest of Buccaneers

François L'Olonais has the terrible distinction of being the cruellest and most depraved of all buccaneers, a title for which there is some stiff competition. Infamous for not taking prisoners, L'Olonais preferred to simply execute his captives, usually by beheading them. The bloodthirsty buccaneer is presented as a grotesque madman in Alexander Exquemelin's influential record of the period, The Buccaneers of America (published in English in 1684). The work was immensely popular thanks to its often exaggerated and colorful biographies. L'Olonais' slaughter of his hapless victims earned him a nickname as the 'Flail of the Spanish' (Fléau des Espagnols). In one infamous anecdote, the French buccaneer cut out the heart of a captive, chewed a bit off, and then stuffed it into the mouth of another captive. As it turned out, L'Olonais' harsh treatment of captives worked against him since Spanish crews and settlers now fought to the death rather than surrender and receive the same fate anyway.

L'Olonais was sometimes on the receiving end of violence. In one episode, he and his men were set upon by an indigenous tribe after their ship was wrecked on the Campeche coast of Mexico. While most of his men were killed, L'Olonais escaped by covering himself in blood and hiding amongst his fallen crew. The buccaneer was, at least, resourceful, and he managed to reach the safety of Tortuga in a stolen canoe.

The experience with the Campeche Indians did not deter L'Olonais from his harsh tactics. Attacking an anchored warship in a port in Cuba, he captured a number of Spaniards who were all beheaded except one who was sent with a letter to the governor of Havana. The note informed the Spanish authorities that L'Olonais would continue to show no mercy to captured Spaniards and all would be executed. Meanwhile, the buccaneer took over the warship for his own use and continued to plague the waters of the Spanish Main, this time off the coast of Venezuela.

The Attack on Maracaibo

Privateering buccaneers, strictly speaking, were only authorised by their respective colonial authorities to attack Spanish shipping and not ports. However, a war between France and Spain from 1667 to 1668 meant that the coast of Venezuela became a legitimate target. L'Olonias attacked the Venezuelan portion of the Spanish Main in 1667. Leading some 600 men in eight ships, L'Olonais' force was composed of mostly French buccaneers from both Hispaniola and Tortuga. They immediately captured two ships before even arriving in Venezuela, taking large quantities of silver, gems, muskets, gunpowder, and cacao. Maracaibo was L'Olonais' destination, then a settlement of some 4,000 people and the centre of the regional pearl trade. The port battery guarding the entrance to Lake Maracaibo was easily overwhelmed; the buccaneers had attacked the fortifications from the land side and so avoided the 16 cannons pointing out to sea.

The buccaneers sacked Maracaibo, but finding any booty was another matter as the locals had already fled with what valuables they could carry. L'Olonais sent his men out into the woods over the next two weeks to hunt down the hiding inhabitants. 20 Spaniards were caught and tortured and summarily butchered. L'Olonais then moved on to Gibraltar on the other side of Lake Maracaibo. Here the garrison used their eight cannons well and put up stiff resistance. Around 70 of the buccaneers were either killed or wounded. Ultimately, the garrison capitulated, with 200 dead and 150 prisoners taken. More booty was gathered and more horrors befell the local population during a four-week rampage. L'Olonais, as was the usual strategy of the buccaneers, threatened to burn the settlement to the ground if a ransom was not forthcoming. The residents stumped up 10,000 silver pesos (pieces of eight).

The buccaneer force then returned to Maracaibo and extorted an even bigger ransom from the Spanish authorities there for its safe return. This time the buccaneers got 30,000 pieces of eight. The expedition was a huge success, and L'Olonais and his crews returned to Tortuga to spend their ill-gotten gains as quickly as possible on wine, women, and gambling. After three weeks, the cash was spent and the sea began to call once again.

Honduras & Death

Another large expedition was soon in the planning, this time to attack the coast of Nicaragua. Amassing a force of 700 men in six ships, L'Olonais once again led the expedition to raid Spanish possessions. This time the buccaneers had less luck and their fleet was becalmed in the Gulf of Honduras. Still, it made no difference where their plunder came from and so in 1668 the buccaneers attacked the Honduran coast, including the small settlement of Puerto Caballos. Once again, most of the locals had fled at the first sight of the buccaneers' ships, but those unfortunate enough to be captured were tortured to reveal the whereabouts of anything valuable. Alexander Exquemelin gives the following account of L'Olonais' torture methods:

When L'Olonais had a victim on the rack, if the wretch did not instantly answer his questions he would hack the man to pieces with his cutlass and lick the blood from the blade with his tongue, wishing it might have been the last Spaniard in the world he had thus killed.

(quoted in Rogozinski, 203)

L'Olonais could not find any plunder of note, even a captured Spanish ship turned out to have an empty hold. A raid inland only met with an ambush by a Spanish force and the capture of San Pedro, a tiny settlement with nothing of value to the buccaneers. The whole enterprise was a failure, and many of L'Olonais' captains deserted the expedition.

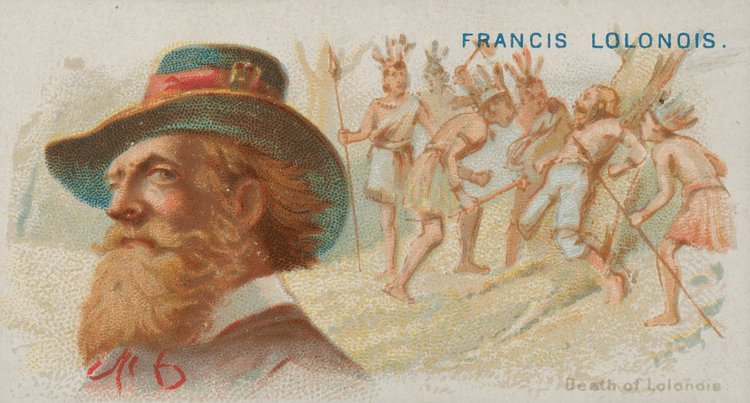

Like most nasty villains, L'Olonais did get his comeuppance, and in his case, it seems a strangely apt one. Working his way down towards the isthmus of Panama in 1668, he captured a Spanish galleon, but unfamiliar with this type of heavy and unwieldy ship, his crew lost control of it in the difficult waters and ran the ship aground on the Mosquito Coast of Nicaragua. L'Olonais had his crew begin to build rudimentary boats, but when leading a foraging trip inland, he was attacked and defeated by a Spanish force. L'Olonais escaped to sail down the coast, but in another foraging trip in the Gulf of Darien, he was captured by cannibals. Amongst the captives, L'Olonais was served last, so to speak. He was slowly cut to pieces until he died, and then he was roasted. The choicest parts were eaten, and what remained was burned to ashes and scattered in the wind.