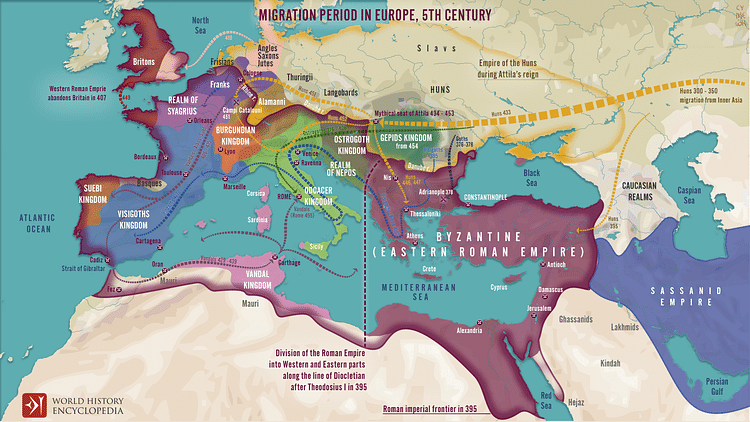

The Franks were a Germanic people who originated along the lower Rhine River. They moved into Gaul during the Migration Age, where they established one of the largest and most powerful kingdoms in Europe after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Their influence, which peaked under Charlemagne (l. 742-814), helped define Europe in the Middle Ages and beyond.

Origins & Identity

The Roman conquest of Gaul, completed by Julius Caesar in the 1st century BCE, fixed the Rhine River as the edge of the Roman world. The river, therefore, became the political barrier between 'civilization' (i.e. Rome) and the 'barbaric' Germans who lived beyond; in the Roman mind, these Germans were stereotypically tall, blond, filthy, and prone to violence. For centuries, the Roman legions of the Rhine frontier kept the Germans at bay, until the gradual breakdown of Roman authority during periods like the Crisis of the Third Century allowed certain Germanic peoples to make incursions into Roman land.

One of these Germanic groups was the Franks, who first entered the annals of history in the 3rd century CE. The early Franks were not a unified people, but rather a loose confederation of individual tribes that lived along the lower Rhine, each with a separate identity. Some modern scholars think it more accurate to label them a 'tribal swarm' than a confederation, since they only seemed to band together in offensive or defensive campaigns. When they did join forces, however, these tribes were collectively known as 'Franks', a word that meant 'the fierce', or 'the brave'; only later would it mean 'the free', which became the definition most favored by the Franks themselves. Some of the Germanic tribes associated with the Franks included the Chamavi, the Chattuari, the Bructeri, the Salians, the Ripuarians, and several others. The Salians and Ripuarians would eventually emerge as the most dominant tribes.

There are several different accounts of the origins of the Franks. The 6th-century historian Gregory of Tours states that they originated in Pannonia and migrated to the Rhineland before moving on to settle in Thuringia and Belgium. The Chronicle of Fredegar and the anonymously written Liber Historiae Francorum offer more legendary accounts, and each ties Frankish origins back to the Trojan War. According to these myths, King Priam led 12,000 Trojan refugees to Pannonia where they founded the city of Sicambria. Some stayed there while others followed a leader named Francio to the Rhine, where they became known as 'Franks'. The connection to Troy was likely an attempt by the Franks to give themselves a bloodline on equal footing with that of the Romans, who also claimed descent from the Trojans. While this origin tale is certainly mythical, some modern scholars like Ian Wood state that there is little reason to believe the Franks embarked on any great migration at all, and that they had originated in the Rhineland.

Religion, Language, & Law

The Franks famously converted to Christianity during the reign of King Clovis I (r. 481-511). Prior to that, however, they likely practiced a variation of old Germanic paganism. This mythology centered around multiple deities, which were linked to local cult centers, with forests held in special consecration. Gregory of Tours, writing from the biased point of view of a Catholic bishop, describes their early religion in these terms:

[the Franks] fashioned idols for themselves out of the creatures of the woodlands and the waters, out of birds and beasts: these they worshipped…and to these they made sacrifices (II.9).

While the early Franks likely believed in some iteration of Wuodan (Odin), there were some symbols specific to them. The image of the bull, for instance, seems to have been particularly significant; a sea beast with a bull's head, called the Quinotaur, was said to have been the father of the Frankish leader Merovech, while a golden bull's head was discovered in the tomb of the Salian king Childeric I.

Like their religion, the Frankish language, too, started off as Germanic before its gradual Romanization. The original language was a West Germanic dialect, different from both Gothic, or East Germanic, and Old Norse, or North Germanic (James, 31). When the Franks settled in Belgium and northeastern Gaul, they intermingled with the local Gallo-Roman population, causing linguistic changes for both groups of people. In northern Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany, where early Frankish presence was most significant, people began to speak Germanic-influenced languages that would evolve into Old Dutch and Flemish. In modern France and southern Belgium, where the Franks would not establish a permanent presence until later on, Romance languages flourished like Walloon and Old French. This linguistic barrier, defined by the early settlement of the Franks, is still visible today.

Prior to their unification, each Frankish tribe followed its own set of laws, memorized by a law speaker. Between 507 and 511, during the reign of Clovis, a civil law code was written to apply to the new Frankish kingdom which became known as Salic Law, named after the dominant Salian tribe. The law code was written primarily in Latin and dealt mainly with inheritance and criminal justice and would form the basis for some future European legal systems. Another Frankish law code, the Ripuarian Law, was written around 630 as the Ripuarians rose to prominence within the Kingdom of Austrasia.

Settlement in Gaul

The Franks were first mentioned by a contemporary Roman source in 289 CE, although the Franks had likely been fighting the Romans for decades prior; a Roman marching song dating to the 260s references the deaths of thousands of Franks, while archaeological evidence suggests the Franks were attacking Roman Gaul as early as the 250s. By the late 3rd century, the Franks had mounted numerous attacks on Roman territory both by land and by sea; Frankish pirates were recorded to have sailed into the Mediterranean and raided as far as North Africa.

These incursions demanded the attention of the Roman emperors, who launched several successful campaigns against the Franks. In 289, the Frankish king Gennobaudes was recorded to have surrendered to the Roman emperor Maximian (r. 286-305). In 307, the Frankish tribe of the Bructeri was defeated by Constantine I (r. 306-337) who threw two Bructeri leaders to the beasts in the arena at Trier. The victorious Romans captured many Franks during these campaigns; rather than ransom or execute them, the Romans decided to settle some Frankish prisoners on Roman land as laeti. This meant that they were given land within the Roman Empire in exchange for military service. By the mid-4th century, entire Frankish tribes were being settled on Roman land under similar foederati treaties; the Salian Franks, for instance, were settled in Belgic Gaul in 358, while the Ripuarian Franks were settled on the Rhine around the city of Cologne. These tribes, once enemies of Rome, now bolstered the Roman army with their own troops and defended the empire's frontier from barbarian incursions.

This relationship allowed certain Franks to prosper within the Roman power structure. For instance, Mellobaudes was a Frank who became consul multiple times, while Silvanus was a general of Frankish descent who was able to make an unsuccessful bid for the imperial throne before being killed in 355 CE. One of the most successful Franks was Arbogast, who rose through the ranks of the Roman army to become magister militum (master of soldiers) of the Western Roman Empire. This position allowed Arbogast to rule the empire in all but name, directly overseeing administration and rarely reporting to Emperor Valentinian II (r. 375-392). When Valentinian II died, Arbogast replaced him with another puppet emperor, Eugenius, and continued to rule until he was killed by an Eastern Roman army in 394 CE, at the Battle of the Frigidius River.

The Franks who reached such lofty positions tended to have been heavily Romanized and were unrepresentative of the Frankish people. Indeed, while many Franks had become aligned with Rome, some were still counted among the empire's enemies, such as Sunno and Marcomer, Frankish leaders who attacked Gaul in 388. But by that point, a large number of Frankish tribes had made their homes on Roman soil and were continuing to aid the Romans militarily; in 451, the Franks fought alongside the Romans against the Huns at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields.

Yet the death of the Roman general Flavius Aetius in 454 marked the steady disintegration of Roman authority in Gaul, allowing Frankish groups like the Salians to rise to power. By offering the local Gallo-Roman population protection and employment, things that could no longer be guaranteed by Rome, the Salians were able to solidify their power in northeastern Gaul. Under the rule of Childeric I (r. 458-481), the first king of the Merovingian Dynasty, the Salians established themselves as the most powerful of the petty Frankish kingdoms scattered throughout Gaul; by the time when Childeric died in 481, the groundwork had been lain for his son and successor, Clovis I, to conquer Gaul and unite all the Franks under his rule.

Merovingians

Clovis began his conquest of Gaul in 486, when he defeated Syagrius, the last major Roman official in Gaul, and captured the city of Soissons. From this power base, he campaigned against the Alemanni, the Burgundians, and the Visigoths, expanding Frankish influence further into Gaul and Aquitaine. He converted to Nicene Christianity (Catholicism) around 496, beginning the gradual Christianization of the Franks. His conversion was important for making Frankish Gaul a bastion for Catholicism rather than Arianism, a rival sect of Christianity that was favored by other barbarian kingdoms. Toward the end of his reign, Clovis ruthlessly took over the other Frankish kingdoms and had their leaders killed; for the first time, the Franks were united as a single people. At the time of his death in 511, Clovis ruled as "King of All the Franks" and was the master of all Gaul except Burgundy, Provence, and Septimania.

Upon Clovis' death, the Merovingian kingdom was divided among his four sons, setting a dangerous precedent for future successions. Initially, the sons worked together to build on their father's conquests, conquering Burgundy, Provence, and Thuringia in the 530s. The sons of Clovis campaigned against the Visigoths in northern Spain, sent armies into Italy, expanded Frankish influence into Bavaria, and compelled the Saxons to pay them an annual tribute of 500 cows. After the death of the Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great in 526, the Merovingian kingdom could rightfully be recognized as the largest and most powerful barbarian successor state to have replaced Rome in western Europe.

But despite this success, the Merovingian rulers often quarreled and were constantly looking for ways to undermine and plot against one another. In 558, Clovis' youngest son, Chlothar I (r. 511-561) emerged as the victor; after decades of rivalry with his brothers that included murdering his nephews and executing his own son, Chlothar I reunited the Frankish kingdom under his own rule by outliving his brothers and inheriting their lands. However, his reign lasted less than three years before he died in 561, and the kingdom was partitioned once again among his own four sons, at which point the three distinct Merovingian kingdoms of Neustria, Austrasia, and Burgundy began to take shape.

The death of Chlothar I led to a new round of schemes, civil wars, and assassinations, fueled by the rivalry between Queen Brunhilda of Austrasia (l. c. 543-613) and Queen Fredegund of Neustria (d. 597). The conflict lasted for decades and erupted into proxy wars between these queens' sons and grandsons until 613 when Queen Brunhilda was finally defeated and executed by King Chlothar II (r. 584-629), the son of Fredegund. Chlothar II reunited Francia and adopted Clovis' old title "King of All the Franks", but his victory came at a hefty price. In order to secure his position, he was forced to grant massive concessions to the nobility. The 614 Edict of Paris codified the traditional rights of the aristocracy and decentralized power into the hands of regional elites. The power of the mayor of the palace (roughly equivalent to a prime minister) was also increased, and in 617, these mayors became appointed to their offices for life and were allowed to legislate in their own kingdoms as they saw fit. As scholar Susan Wise Bauer remarks, Chlothar II had made a "devil's deal" with these concessions; he had secured his own power at the expense of Merovingian crown authority (251).

Chlothar II's son, Dagobert I (r. 623-639), ruled as the last Merovingian king to wield significant royal authority. Although the Merovingians continued to reign for more than a century after Dagobert's death, their authority was gradually eclipsed by the mayors of the palace, who soon became the true powers behind the throne. The decline of Merovingian power led the chronicler Einhard to refer to the later Merovingian rulers as "rois fainéants" or "do-nothing kings".

Carolingians

In 687, the Kingdom of Austrasia defeated Neustria and Burgundy at the Battle of Tetry and became the dominant kingdom in Francia. This increased the power of the aristocratic family known alternatively as the Pippinids or the Arnulfings, which had continually served as mayors of the palace of Austrasia since the days of Dagobert I. Yet despite this newfound influence over the entirety of Francia, the Pippinids could not take the throne for themselves and continued to rule through their Merovingian puppets; the Franks would not yet accept any other dynasty to rule over them. This attitude would change after the dynamic reign of Charles Martel (l. c. 688-741), a scion of the Pippinid clan who became mayor of the palace of Austrasia in 715.

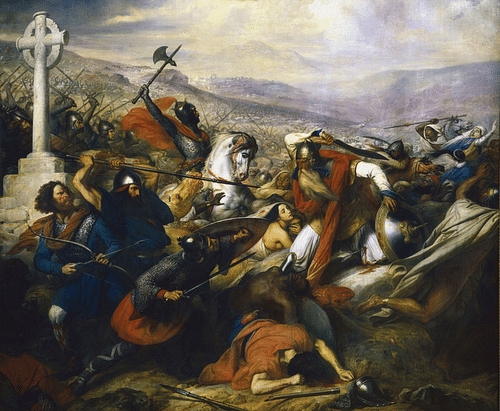

Charles famously led the Franks to victory over the Umayyad Caliphate at the Battle of Tours in 732, thereby solidifying his role as de facto ruler of Francia. By the time his Merovingian puppet king, Theuderic IV, died in 737, Charles' personal influence had reached such a point that he did not even bother to install a new ruler, and the throne remained vacant until Charles' death in 741. The Merovingians were then restored, but the illusion that the dynasty held any power had been permanently shattered; in 751 Charles' son, Pepin the Short (r. 751-768), secured the support of Pope Zachary to overthrow the last Merovingian king. Pepin took the throne for himself, and the Carolingian Dynasty was born.

Pepin died in 768, at which point the Frankish lands were divided between his sons, Carloman I (r. 768-771) and Charles, the latter of whom is better known to history as Charlemagne (r. 768-814). The two brothers ruled together as co-kings until Carloman's death in 771, at which point Charlemagne became the sole king of the Franks. From his court at Aachen, Charlemagne ruled with the support of the Frankish aristocracy and the medieval Church, though he was constantly away on campaign. In 774, he conquered the Lombards and assumed the title "King of the Franks and Lombards". He campaigned against the Basques in the Pyrenees, the Saracens in Spain, and the Avars in Hungary. These conquests did not come without great difficulty, as exemplified by the Saxon Wars, the name given to Charlemagne's grueling conquest of Saxony which lasted intermittently from 772 to 804. Despite the longevity of the conflict, Charlemagne ultimately prevailed; he incorporated Saxony into his realm and forcibly converted the pagan Saxons to Christianity. By his death in 814, Charlemagne had doubled the size of the Frankish realm.

On 25 December 800, Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III (r. 795-816). Likely an attempt by the papacy to establish control over Charlemagne, the coronation also served to bolster Carolingian prestige and Frankish power in Western and Central Europe. Charlemagne's empire, later referred to as the Carolingian Empire, stretched from northern Spain to Hungary and was largely dominated by the Franks. It coincided with a period of cultural activity known as the Carolingian Renaissance, which saw an increase in literature, writing, music, jurisprudence, and scriptural studies.

When Charlemagne died in 814, his empire (often considered an early phase of the Holy Roman Empire) was inherited by his only surviving son Louis the Pious (r. 813-840). Three years after Louis' death in 840, the empire was partitioned into three distinct kingdoms to prevent civil war between his sons; these kingdoms were East Francia, Middle Francia, and West Francia. These kingdoms persisted until the decline of the Carolingian Dynasty at which point East Francia became the Kingdom of Germany, the Kingdom of West Francia became the Kingdom of France, and Middle Francia became the kingdoms of Lotharingia and Italy. Although the term 'Franks' continued to be used after this point, it no longer had an ethnic definition but was used to refer more broadly to Catholic Western Europeans. During the Crusades, for instance, Eastern Orthodox Christians and Muslims referred to crusaders of Western and Central Europe as 'Franks' or 'Latins'.

Conclusion

Once a loose confederation of Germanic tribes situated along the lower Rhine, the Franks would reach such heights of power and influence that for a time their name became synonymous with 'Western European'. Despite initially being viewed by the Romans as uncivilized 'barbarians', the Franks went on to influence the development of Europe, linguistically, legally, culturally, and religiously, and they even replaced the Romans themselves as the new emperors in the West after the coronation of Charlemagne. Certainly, the Franks played a significant role in the Early Middle Ages and in the birth of some of the states of Europe.