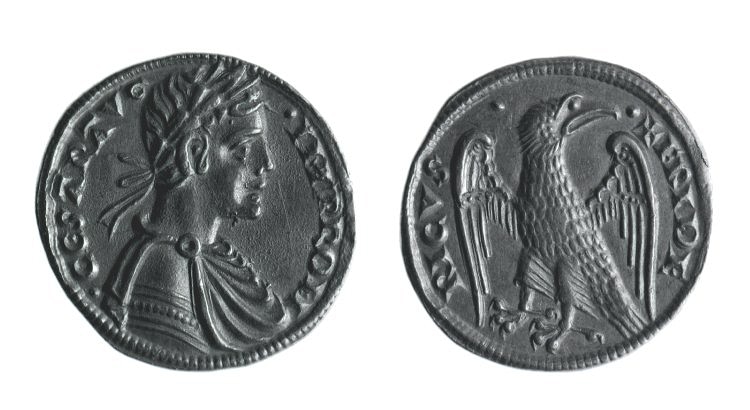

Frederick II (l. 1194-1250 CE) was the king of Sicily (r. 1198-1250 CE), Germany (r. 1215-1250 CE), Jerusalem (r. 1225-1228 CE), and also reigned supreme as the Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1220-1250 CE). He was born in Jesi in 1194 CE but spent his childhood in Palermo. He belonged to the Hohenstaufen Dynasty (1079-1268 CE) of Swabia, which ruled over the Holy Roman Empire from 1138 CE to 1268 CE. His life was spent struggling over the power dynamics with the medieval church, though he failed in subduing the Papacy, later European rulers would follow in his footsteps and succeed. He is most famous, however, for his involvement in the Sixth Crusade (1228-1229 CE) which returned Jerusalem to Crusader dominion via a peace settlement with the Ayyubid Sultan of Egypt: al-Kamil, but his efforts remained unappreciated. The Papacy used religious propaganda to preach a crusade against him, but he died naturally in 1250 CE. He also founded the University of Naples in 1224 CE, the first-ever state university in medieval Europe.

Early Life

Frederick II was the only son of Henry VI (King of Germany r. 1169-1197 CE; Holy Roman Emperor r. 1191-1197 CE) and Constance (l. 1154-1198 CE), the daughter of Roger II (r. 1130-1154 CE), the Norman king of Sicily. His other grandfather was the legendary German Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa (r. 1152-1190 CE). He was born in Jesi, Italy in 1194 CE and spent most of his life in the court of Palermo in Sicily. His father died in 1197 CE, when he was just three, and he was coronated the next year as the king of Sicily with his mother as regent. Constance alienated the German lords, who had served under his father, to aggrandize her authority. Her main rival was Markward (d. 1202 CE), a German lord who claimed the regency of the young sovereign but was exiled.

Constance died after ruling for a little over a year. In her will, she left young Frederick under the guardianship of Pope Innocent III (l. c. 1160-1216 CE). This move was not simply motivated by her devout Catholic faith but also due to a practical reason; she had to assure that her son's position, who was a minor, remained inviolable. Papal involvement, however, proved ineffective in securing Sicily from Markward, who seized Frederick's realm, only to die a few years later. A German captain of Palermo, William of Capparone then took over, only to be deposed in 1206 CE by Walter of Palearia, the ex-chancellor of the Kingdom of Sicily.

Rise to Power

Frederick dismissed his guardian in 1208 CE and now sought to restore control over Sicily. In 1209 CE, Innocent III arranged for Frederick, who was 14 at that time, to be married to a 30-year-old Spanish princess, Constance of Aragon (l. 1179-1222 CE). This marriage was a political move and allowed Frederick to acquire a sizeable army that he used to consolidate his hold over Sicily. Constance also bore Frederick's first son, Henry VII (l. 1211-1242 CE). His queen advised him in important matters of the state, and, upon her death in 1222 CE, Frederick is said to have placed his crown on her statue as an acknowledgment of her services.

The king of Sicily was also entitled to rule over his father's dominion: the Holy Roman Empire. The empire (962-1806 CE) spanned over Germany, Sardinia, and parts of Northern Italy and served as the protector of the Catholic Church.

This freed Otto's subjects from their oaths and exposed his land to attacks from rival European powers. Philip Augustus (r. 1180-1223 CE), the king of France exploited the situation and invaded Otto's realm. Otto had close ties with the English, and the French king wished not to let his enemies gain the upper hand. Frederick rode to Germany in 1212 CE and by securing an alliance with Philip, he duly chastised Otto's forces and was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt, in 1215 CE. After Otto's death in 1218 CE, Frederick's claim was unchallenged.

Consolidation of Power

Pope Innocent III died in 1216 CE and was succeeded by Honorius III (l. 1150-1227 CE). The new pope demanded that the emperor repay the papacy for its kindness and Frederick agreed to separate Sicily from the lands of the Holy Roman Empire and to lead a crusade to the Holy Land. The Papal States could not allow the lands in the north and south to be united under one person, exposing papal territory to an invasion from both sides.

He persuaded the Pope that Sicily was vital in supporting a crusade, hence he did not cede it, and he remained too preoccupied to join the armies of the Fifth Crusade (1218-1221 CE) when they departed Europe. Meanwhile, Frederick had set upon stabilizing and glorifying his realm; he even established the first-ever state university in medieval Europe, the University of Naples in 1224 CE. With Sicily set to order and the collaborators of pretenders crushed, Frederick could sigh in relief.

Friction with the Catholic Church

To further pique Frederick's interest in the Holy Land, the Pope arranged a marriage for him with the teenage daughter of King John of Jerusalem (r. 1210-1215 CE, also known as John of Brienne): Yolande of Brienne (l. 1212-1228 CE, also known as Isabella II of Jerusalem). Jerusalem was not under crusader control but the king's seat persisted as did the hope that the holy city would be reconquered. King John offered the hand of his beloved daughter on the condition that Frederick would not lay claim on the throne of Jerusalem for as long as John lived. The couple was married in 1225 CE in Brindisi, Southern Italy. According to some historians (although others disagree), Frederick broke his promise and the queen was mistreated, as described by historian Harold Lamb:

Not a week had passed before John found his daughter unattended and weeping in the Brindisi castle. What she endured at Frederick's hand was never known… The following day Frederick made sudden demand upon him to yield the scepter of his kingdom... (210)

The Pope's patience was running out, and Frederick, now the King of Jerusalem (r. 1225-1228 CE), set out for the Holy Land in 1227 CE but was stricken by malaria and had to turn back. He recovered but delayed his departure to await the birth of Yolande's child, a boy. The queen, aged 17, died in 1228 CE, giving birth to her son, Conrad (l. 1228-1254 CE). Frederick could no longer claim to be the king of Jerusalem but he continued to do so.

Pope Honorius III had died in 1227 CE, and his successor, Gregory IX (d. 1241 CE) was not so patient. He drew up a series of charges against Frederick (including his inability to fulfill his Crusader vows). Not only did the Pope excommunicate the emperor but he also refused to admit imperial envoys in his presence; such insults pushed the emperor to reply in kind.

Frederick & al-Kamil: The Sixth Crusade (1228-1229 CE)

Frederick had opened up a channel of communication with the Ayyubid Sultan of Egypt al-Kamil (r. 1218-1238 CE) since 1226 CE. This man was the nephew of the great Saladin (l. 1137-1193 CE) who had secured Jerusalem for Islam in 1187 CE; he, however, was willing to give away what his ancestors had fought and died for. Al-Kamil needed to extend his authority beyond Egypt into lands that were once held united under Saladin. He needed to spare himself a war with the Crusaders to fight his brother, al-Mu'azzam (r. 1218-1227 CE), the Sultan of Damascus.

On February 18, 1229 CE, the treaty of Jaffa was signed between the Holy Roman Emperor and the Sultan of Egypt. Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Nazareth, and part of the Levantine coast was in European hands along with a pilgrim route to Jaffa. In return, Frederick promised free passage to the Muslims, and possession of the Temple Mount and Al Aqsa mosque; the city walls which had been pulled down beforehand were not to be rebuilt. Frederick unceremoniously crowned himself in the Holy Sepulchre and thus ended his venture to the Holy Land. He soon made it back to his domains in the west which were under a dire threat from Gregory IX and John of Brienne.

The Emperor's Return

Frederick raced back to his realm to chastise the intruders. In his absence, the Pope had sent armies to encroach on his lands. Upon his return in 1229 CE, Frederick defeated the papal army but did not attempt to attack papal holdings in Italy. The first phase of the war ended in 1230 CE with the treaty of Ceprano signed between Gregory and Frederick. The emperor further strengthened his control over the kingdom of Sicily and extended centralized authority over the realm via the Constitutions of Melfi (1231 CE).

In Germany, his absence had led to problems. Henry VII was alienating the German princes and even seeking support from non-German cities. This change in policy was threatening Hohenstaufen control over Germany and when Henry refused to be set straight, Frederick made his move. The emperor brought only his influence into Germany in 1235 CE, and this proved to be enough. Henry, seeing that his supporters had deserted him and that his rebellion had died out, begged for mercy. The emperor seized all titles and power from his son and sentenced him to imprisonment; he died in 1242 CE. Frederick's other son, Conrad IV (r. 1237-1254 CE) was elected as the new king of Germany, and two years later, he was also hailed as the King of the Romans (1239 CE) in Vienna.

War with the Papacy Resumed

The fighting with the Pope restarted owing to a minor dispute over lands in Lombardy. The Lombards, backed up by the Pope, resisted Frederick's authority but their forces were defeated decisively in the battle of Cortenuova (1237 CE). The emperor then received the news in 1239 CE, that he had yet again been excommunicated.

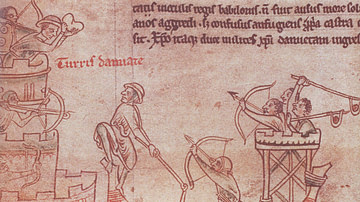

Although vehement in its opposition to Frederick, the Papacy showed shocking neglect towards the Mongol threat advancing fast on Europe and the real Crusader cause in Egypt. The Mongols had risen from the steppes of Asia in the early 13th century CE, and after sweeping resistance in Asia, they started their advance on Eastern Europe in 1236 CE. They crushed a European confederacy at the Battle of Legnica (1241 CE) and incurred severe losses upon Poland and Hungary from 1241 to 1242 CE. Mongol emissaries approached Frederick, demanding his submission to their supreme leader Ogedei Khan (r. 1229-1241 CE), but Frederick ignored them. Knowing the tactics of Mongol warfare, Frederick strictly forbade his subordinates from engaging them in the open. Instead, he instructed them to stockpile on resources and to hold castles and other strongholds. After many fruitless raids, the Mongols were forced to turn back in 1242 CE, when the news of their leader's death reached them.

Pope Innocent IV (l. c. 1195-1254 CE) started his tenure in 1243 CE. Like Gregory, he too advocated the use of licensed violence and called for an "anti-Staufen Crusade". He excommunicated and deposed the emperor in 1245 CE; Frederick's response was:

I have not yet lost my crown, neither will pope or council take it from me without a bloody war! (Abulafia, 375)

Innocent incited rebellion against Conrad IV in Germany in 1246 CE. This uprising was initially successful but the papal-backed belligerents were defeated afterwards. Frederick also strengthened his position in Germany by acquiring the Duchy of Austria. On the Italian front, Frederick employed diplomacy, and by securing a marriage alliance with the marquis of Monferatto, through his illegitimate son Manfred, Frederick found another ally.

The Pope preached a crusade against Frederick on the pretext of protecting Rome, the center of Christian faith from a "Muslim-loving" emperor, who wished to destroy Christianity. He was branded as a heretic and the anti-Christ, prompting many of his foes to take up arms against him. All of these accusations were convenient excuses used by the Pope to veil his actual reasons. Innocent wanted:

- Supreme authority over the Holy Roman emperor, whom the Pope could bless and depose at will.

- Papal control over Sicily, instead of handing it to someone who held power in the north as well.

- Supreme authority over the monarchs of Europe.

- To make an example of Frederick to deter others from emulating him.

This crusade has been described by David Abulafia as the "first large scale attempt to use crusade as an instrument for the defeat of the papacy's political enemies within Europe" (386).

Death & Legacy

It was not the Pope's crusade that triumphed over Fredrick, but his ailment. Before he had a chance of winning back lost ground, he died of dysentery in 1250 CE in Castel Fiorentino, in Apulia, Southern Italy. He was buried in the Cathedral of Palermo. The throne passed to his only living legitimate son Conrad IV, but the new king died just four years later in 1254 CE, leaving the throne to his son Conradin (r. 1254-1268 CE), also known as Conrad V. He continued resisting the Pope but was finally defeated and executed in 1268 CE.

Frederick would forever be immortalized in the annals of history by his nickname, Stupor Mundi, Wonder of the World. He had a passion for adventure and women, mastered falconry, horse-riding, lancing, and spoke six different languages. Despite the papal propaganda devised to weaken his support, Frederick was indeed a Christian ruler, although not a pious one. Though the Papacy survived this war, their dominance was nearing its end. The Pope exploited the religious fervor of Europeans, and this abuse of power ultimately led to the downfall of papal authority, in essence making Frederick successful, posthumously. His biggest achievement was the resolution of the Holy Land issue through negotiations rather than brute force. He was without a doubt, a ruler born ahead of his time, a rational monarch surrounded by a sea of religious zealots, Stupor Mundi!