The French Consulate was the government of the First French Republic from 10 November 1799 to 18 May 1804, spanning the last four years of the Republic's existence. Headed by Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) as First Consul, the Consulate served as a bridge between the French Revolution (1789-1799) and the First French Empire (1804-1814; 1815).

During the period of the Consulate, Bonaparte consolidated his power while slowly moving in the direction of authoritarianism. He secured the support of the French populace with his victory at the Battle of Marengo (14 June 1800) and with the Peace of Amiens (25 March 1802), the latter of which ended the decade-long war between France and the United Kingdom. The period also saw the enactment of some of Bonaparte's longest-lasting political achievements, including the Concordat of 1801 and the Civil Code of the French, better known as the Napoleonic Code. By centralizing the state government and reviving many of the mechanics of France's Ancien Régime, Bonaparte undermined some of the accomplishments of the French Revolution and paved the way for his own elevation to Emperor of the French in May 1804.

A Coup Within a Coup

The Coup of 18 Brumaire Year VIII (9-10 November 1799) brought an end to the ineffective government of the French Directory and, in the view of many historians, ended the French Revolution as well. On the wet and gloomy morning of Monday 11 November 1799, the victors of the coup met at the Luxembourg Palace to begin the process of writing a new constitution and redefining the French Republic. These men included Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès, who had orchestrated the coup; Roger Ducos, his supporter; and Napoleon Bonaparte, a popular young general who had been brought on as the military muscle of the conspiracy.

Most people expected France's next constitution to be written primarily by Sieyès, an experienced statesman who had already had a hand in two of France's revolutionary constitutions (that of 1791 and the unimplemented Girondist constitution of 1793). Yet Bonaparte, who was expected to act as the most junior partner in this provisional government, had no faith in Sieyès' ability to write a constitution, believing it would be watered down with unnecessary checks and balances to centralized power. "He was not a man of action," Bonaparte later wrote of Sieyès. "Knowing little of men's natures, he did not know how to make them act. His studies have always led him down the path of metaphysics" (Roberts, 231). Moreover, the wildly ambitious Bonaparte was not about to play third fiddle in any government. At the first meeting of the provisional consuls, Bonaparte claimed the large chair in which the president of the old Directory had sat; though the consuls agreed to rotate the presidency every 24 hours between them, the implicit message of Bonaparte's choice of seating was clear.

Throughout the end of November, Sieyès worked on his constitution. He envisioned a government in which a head of state, called the 'Grand Elector', oversaw the work of the Senate as well as the other two consuls; clearly, Sieyès hoped to claim this position for himself. Bonaparte moved to undermine Sieyès' plan, putting his propagandists to work printing posters that emphasized his heroic role in destroying a supposed Jacobin plot on 18 Brumaire, mentioning neither Sieyès nor Ducos. He won over several important politicians to his side including Boulay de la Meurthe, chairman of the committee that who been appointed to draw up the constitution, and Pierre Claude Daunou, whose plan for a government with concentrated authority was more in line with Bonaparte's own thoughts.

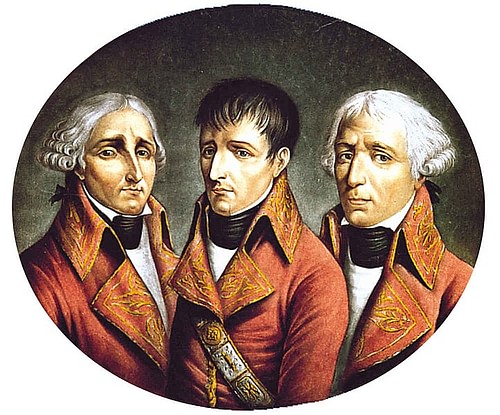

Once the Bonapartist faction won over the influential Jean-Jacques-Régis de Cambacérès, it was clear that Sieyès and his small faction of supporters had been outmaneuvered; when the Constitution of Year VIII was finally implemented on 25 December 1799, it reflected Bonaparte's idea of a centralized republic. Bonaparte was made First Consul, the effective head of state, and was supported by two lesser consuls, positions that were filled by Cambacérès and the lawyer Charles-François Lebrun. For his part, Sieyès was relegated to the presidency of the Senate and was quietly sidelined from the political sphere.

The Government

The new government centered around the executive branch, which consisted of the three consuls. Bonaparte, as First Consul, was granted the power to make laws, appoint and dismiss government and military officials, and make treaties. He was installed in the Tuileries Palace and given an annual salary of 500,000 francs (compared to 150,000 francs per year for the two other consuls). A deliberative assembly, called the Conseil d'État, was formed to advise the First Consul and help him draft legislation. The Conseil also served as the final court of appeal in legal cases that dealt with administrative law and examined the wording of bills before they were sent to the legislature, both functions that the Conseil d'État still carries out today.

Once bills were written by the First Consul on the advice of the Conseil d'État, they would be sent to the Tribunate, a legislative assembly which could debate the bills but could not vote on them. The bill, and the Tribunate's debate record, would then be sent to the Legislative Assembly, which would hold a silent vote on whether to pass the bill but could not discuss or debate the bill's merits. Alongside these assemblies, there existed a senate, called the sénat conservateur, which was charged with maintaining the integrity of the constitution and amending it, if necessary. These legislative assemblies allowed for the appearance of republican checks and balances, though in reality most of the power rested in the hands of the First Consul, thereby bringing to fruition the concentrated government envisioned by Bonaparte and Daunau.

In February 1800, a national referendum was held to confirm both the Constitution of Year VIII and the new Consular government. All French citizens would be allowed to vote by signing a register that would be kept open for three days (at the time, a citizen was defined as an adult, property-owning male). The referendum was overseen by the minister of the interior, a position occupied by Lucien Bonaparte, Napoleon's younger brother; it is hardly surprising, then, that the records preserved in the Archives Nationales show clear falsification of the voting results made in Lucien's own handwriting (Roberts, 239). Even at a local level, votes were manipulated by officials looking to please the regime in Paris while the public nature of the voting process left voters exposed to intimidation. Since the Bonapartist regime was genuinely popular, the referendum likely would have passed even without such meddling. Nevertheless, the results released on 7 February 1800 made the improbable claim that 3,011,007 voters approved the constitution with only 1,562 against, a 99.5% approval rating.

Consolidating Power

Even with such a massive approval rating, Bonaparte was not yet secure in his power. After eight long years, the French Revolutionary Wars were still raging on the frontiers, and the war-weary French populace was eager to see an end to the fighting. Bonaparte understood the fickle nature of French revolutionary politics and knew that he had no shortage of rivals; to legitimize his new government, he had to give the French people a victory. Beginning on 15 May 1800, the First Consul personally led the Army of the Reserve through the Great St Bernard Pass over the Alps. Arriving in northern Italy, he captured Milan before pursuing the Austrian army, which he cornered near the city of Alessandria.

Believing the Austrians were trying to retreat, Bonaparte relaxed his guard, meaning that his army was taken completely by surprise when the Austrians attacked on 14 June at the Battle of Marengo. Fighting in the scorching summer heat, the French were nearly defeated; the day was saved by the arrival of reinforcements under General Louis Desaix (who was killed in the battle), and by a timely cavalry charge led by General François-Étienne de Kellermann. Bonaparte allowed the defeated Austrians to retreat east of the Trincio River, on the condition that they surrender their forts in Piedmont and Lombardy, thereby ending the Italian theatre of war.

Although Bonaparte nearly lost the Battle of Marengo, his propagandists were able to spin it into a brilliant victory for the First Consul. Six months later, French General Jean Victor Moreau defeated another Austrian army at the Battle of Hohenlinden (3 December), leading Austria to sue for peace. The subsequent Treaty of Lunéville, signed on 9 February 1801, saw Austria recognize France's supremacy in Italy and acquisition of the left bank of the Rhine. A little over a year later, France signed the Treaty of Amiens with the United Kingdom, creating an uneasy peace between the two powers who had been at war continually since 1793.

With the Treaty of Amiens, the French Revolutionary Wars came to an end, beginning a 420-day period of peace in Europe. In France, Bonaparte was hailed as a peacemaker, a reputation he used to amend the constitution. On 2 August 1802, a second referendum was held on the new Constitution of Year X, which, among other things, extended the First Consul's tenure to a life term (it had previously been ten years). Unsurprisingly, this referendum passed with a 99.7% approval rate, and Bonaparte's grip on France tightened.

Reforms

Of course, Bonaparte could not hope to legitimize his new regime through military means alone. Ten long years of revolution had left the French people longing for stability, leaving Bonaparte with the task of mending some of the divisions left over from the Revolution. He began by inviting counter-revolutionary émigrés to return to France and restoring their rights as French citizens, though he made it clear that any émigré properties that had been seized and sold off during the Revolution would not be returned. Easter and Christmas were once again recognized as holidays, the honorifics monsieur and madame replaced the revolutionary citoyen and citoyenne, and the Place de la Revolution in Paris was renamed the Place de la Concorde.

Rejecting the individualistic society propagated by the Revolution as "so many grains of sand", Bonaparte instead advocated for the need to give the French people a sense of "civic direction" by erecting "pillars of granite upon the soil of France" (Lefebvre, 149-150). To achieve this, Bonaparte sought to construct a new class of social elites called 'notables', who would theoretically owe their loyalty to the new regime in exchange for the offices and honors that the Consulate bestowed upon them. Although Bonaparte intended for the system to be apolitical and based on merit, in practice, it favored wealthy men from aristocratic backgrounds. This pool of candidates provided France with its civil servants and diplomats, and this social hierarchy served as the foundation for the system of nobility developed during the Empire. Bonaparte still put an emphasis on merit, however, and established the prestigious Legion of Honor to recognize the civic achievements of the citizenry.

Although Bonaparte himself was hardly the picture of a model Catholic – he had already made war on one pope and would imprison another – he understood the value of religion as a political tool. Since the passage of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy in 1790, the French Revolution had become estranged from the institution of the Catholic Church; clergymen were forced to swear loyalty to the state rather than to the pope, and church properties were seized by the government. During the Reign of Terror (1793-94), some revolutionaries embarked on active campaigns of dechristianization, desecrating churches and terrorizing the devout.

Since then, the status of the Church in France remained somewhat murky, even though large swathes of the French population remained devoted Catholics. The Concordat of 1801, signed between Bonaparte and Pope Pius VII, reconciled France with the Catholic Church. The Concordat did not restore Catholicism as the state religion, nor did it return Church properties, but it did restore much of the Church's civil status in France. The Concordat was celebrated especially in the religiously conservative countryside, though it was unpopular in the army, which still consisted of many ex-Jacobins. The Concordat remained effective in much of France until 1905.

Another major administrative achievement during the Consulate was the creation of the Civil Code of the French, more commonly referred to as the Napoleonic Code. Ancien Régime France had been governed by a confusing web of different, and often contradictory, legal codes that varied from province to province; the south of France, for example, often based its laws on Roman law while the north generally followed customary laws. Bonaparte and his compatriots organized these legal codes, as well as the nearly 14,000 decrees passed by the various revolutionary governments, and condensed them into a single legal code that applied to all citizens. Like the Concordat, the Napoleonic Code became one of Bonaparte's longest-lasting administrative achievements; aspects of the code survive in the legal systems of many European countries and much of Latin America.

The Consulate era also saw the establishment of France's first successful national bank, the Bank of France. French education was overhauled with a new system of elite schools (lycées), the metric system was introduced nationwide, and Ancien Régime era indirect taxes were reintroduced to the chagrin of much of the populace.

Colonialism

The Consulate came to power at a time when France was struggling to hold onto its crumbling colonial empire. In the Caribbean, the colony of Saint-Domingue (Haiti) had been in revolt since 1791. In 1801, Bonaparte dispatched an army led by his brother-in-law, General Charles Leclerc, to crush the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) and reimplement the institution of slavery. This expedition ended in complete failure; Leclerc died of yellow fever in November 1802, and the French expeditionary army met with ultimate defeat at the Battle of Vertières (18 November 1803). After the subsequent withdrawal of French soldiers, Haiti declared its independence on 1 January 1804.

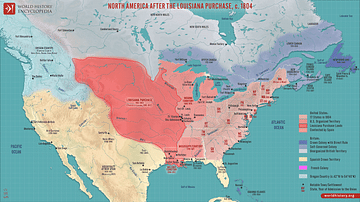

The loss of Haiti convinced Bonaparte to give up his dreams of a colonial empire to rival Britain's, deciding instead to focus on territorial gains on the European continent. Although he had previously promised Spain that he would not sell the Louisiana territory to a third party, Bonaparte sold the entire 2,266,000 km² (875,000 mi²) of territory to the United States for a price of 80 million francs, or less than four cents an acre. With the Louisiana Purchase, Bonaparte sought not only to fund his armies but also to help the United States become powerful enough to rival Britain at sea. This idea would somewhat come to fruition when the United States fought Britain in the War of 1812, occupying British military resources that would otherwise have been used against the French.

Plots & Political Repression

Despite his widespread popularity, Bonaparte was viewed with distrust by former revolutionaries who correctly foresaw the shift away from republicanism. On Christmas Eve 1800, Bonaparte narrowly survived an assassination attempt at the Place du Carrousel when a cart loaded with gunpowder exploded, killing eight people and wounding 26 (a little girl who the conspirators had paid to hold the horse's reins was amongst the dead). Bonaparte responded by cracking down on his detractors on both the political left and right; 130 Jacobins and around 100 royalists were arrested and deported or imprisoned without trial, with many others kept under surveillance. He closed at least 60 of France's 73 newspapers, warning that any newspaper that threatened national unity would be shut down.

In 1804, a British-backed conspiracy was discovered in which French royalists allegedly plotted to kidnap or kill Bonaparte and restore the king-in-exile, Louis XVIII of France, to his throne. Those implicated in the conspiracy and subsequently arrested included General Jean-Charles Pichegru and Georges Cadoudal, a Breton leader of the royalist Chouannerie uprising which had resisted the various French regimes since 1793. Also believed to have been involved in the conspiracy was Louis-Antoine de Bourbon-Condé, Duke of Enghien. The duke was a member of a cadet branch of the House of Bourbon living in the Electorate of Baden as an émigré. Bonaparte reached the conclusion that Enghien was too dangerous to leave alone and sent 200 soldiers to cross the border into Baden, surround Enghien's house, and arrest him. The young duke was charged with plotting to bear arms against France and was shot on 21 March 1804.

The Cadoudal affair (as the conspiracy became known) sent shockwaves throughout Europe, particularly regarding the execution of Enghien, which was viewed by much of Europe as an illegal killing reminiscent of the bloodshed of the Terror. By now, France and the United Kingdom were back at war following the breakdown of the Treaty of Amiens in May 1803, but Enghien's murder turned much of Europe's aristocracy against the French and was one of the reasons for the outbreak of the War of the Third Coalition (1805-1806) and the escalation of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815).

Conclusion

The period of the French Consulate was a time of transition for France. Bridging the gap between the Revolutionary and Napoleonic eras, the Consulate provided France with the stability that many desired. The Consulate's reforms helped bind a divided people together, albeit at the price of some of their newly won freedoms, while Bonaparte's leadership brought a much-needed peace, albeit a temporary one. The Consulate also allowed for Bonaparte to entrench himself in power; by May 1804, all pretensions of republicanism were swept aside when First Consul Bonaparte became Emperor Napoleon I.