The French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802) were a series of conflicts that arose from the tensions surrounding the French Revolution (1789-1799). The wars were fought between Revolutionary France and several European powers, most notably Austria, Prussia, Russia, Spain, and Great Britain. Ten years of conflict resulted in a French victory and the rise of Napoleon.

The Revolutionary Wars are often divided into two stages: the War of the First Coalition (1792-1797) and the War of the Second Coalition (1798-1802). The wars were initially fought in defense of the French Revolution; however, they soon became wars of conquest. By 1802, the French Republic had conquered the Low Countries, northern Italy, and parts of the Rhineland. Some of these lands were incorporated into France directly, others were turned into French client states known as 'sister republics'.

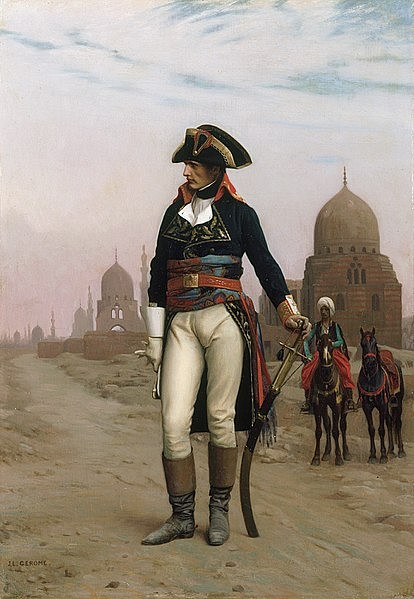

The wars also led to the rise of popular General Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), who seized control of France in 1799 and led the French to victory against the Second Coalition. The Treaty of Amiens, signed on 25 March 1802, marked the end of the Revolutionary Wars, but hostilities would once again break out, beginning the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815). While the Napoleonic Wars were a continuation of the Revolutionary conflicts, they are categorized separately because, instead of being centered around the Revolution, they were caused by the imperial ambitions of Napoleon, who crowned himself emperor in 1804.

Several other conflicts developed because of the Revolutionary Wars; these include the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), and the Quasi-War (1798-1800) between France and the United States. The period of the Revolutionary Wars also covers several French rebellions and civil wars including the War in the Vendée (1793-1796), the Chouannerie (1794-1800), and the Federalist Revolts (1793). Naval battles were also fought in the Caribbean and India, where the belligerents had colonies.

Origins: 1789-1792

The French Revolution began on 5 May 1789, when the Estates-General of 1789 gathered at Versailles to discuss the impending financial crisis. However, an impasse was reached once the Third Estate (commoners) refused to call roll, anxious that the upper two estates (clergy, nobility) would always outvote them. Tensions continued to rise until the Third Estate divorced itself from the proceedings by forming a National Assembly; the attempts of King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) to restore order by calling soldiers into the Paris region backfired when thousands of enraged Parisians stormed the Bastille fortress on 14 July. The National Assembly abolished feudalism in the August Decrees, and, on 5-6 October, the Women's March on Versailles forced the king to accept a constitutional monarchy and return to Paris as a virtual prisoner.

The monarchs of Europe watched all this with a sense of unease. With each gain that it made, the Revolution became more radical, and many believed that it was only a matter of time before it spilled out beyond France's borders. In August 1791, the monarchs of Austria and Prussia issued the joint Declaration of Pillnitz, calling on the powers of Europe to unite against Revolutionary France. While this was meant to simply scare the revolutionaries into pursuing less radical policies, it had the opposite effect, convincing the French that the only way to save their Revolution was through war. By the end of 1791, a pro-war faction, the Girondins, had gained power in Paris; their leader, Jacques-Pierre Brissot, called for a 'universal crusade' to carry the enlightened gains of the Revolution to the oppressed peoples of Europe at the point of a bayonet. On 20 April 1792, the French Legislative Assembly formally declared war on Austria.

Brunswick Invades: 1792

Brissot and his followers had promised a quick war, whereby the citizen-soldiers of France would easily defeat the enslaved soldiers of despotic Europe, but this was not to be the case. In the first days of the war, the French were swiftly defeated by the professional Austrian armies in skirmishes at Quiévrain and Marquain. After one defeat, the undisciplined French soldiers lynched their commanding officer, Théobald Dillon. Things grew bleaker once the commander of the French armies, Marquis de Lafayette, deserted his post and was arrested by the Austrians on his way to the United States.

In May, Prussia joined the war as an Austrian ally, forming the First Coalition. An invasion force gathered along the Rhine, commanded by Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick. However, the Prussian invasion got off to a slow start, due to Brunswick's cautious nature and the dysentery that was ravaging the Prussian ranks. On 25 July, the invaders issued the Brunswick manifesto, promising to destroy Paris should any harm come to the French royal family. Panicking, the Parisians blamed their king for the Prussian invasion. On 10 August, thousands of Parisians massacred the king's Swiss Guards in the Storming of the Tuileries Palace, leading to the imprisonment of Louis XVI and his family.

The Prussians continued on, seizing the key French fortresses of Longwy (23 August) and Verdun (2 September). This left the road to Paris wide open, and the Parisians, once again overcome by fear, attacked the city's prisons, butchering 1,100 counter-revolutionary prisoners in the September Massacres. However, along with paranoid hysteria, the French were also overcome with a determination to defend their homes. They were spurred on by revolutionary leaders like Georges Danton, who promised that with "boldness, again boldness, forever boldness, France will be saved!" (Bell, 130). Indeed, it seemed that boldness would save France when, against all odds, a ragtag French army under generals Charles-François Dumouriez and François-Christophe Kellermann halted the Prussian invasion at the Battle of Valmy (20 September). The miraculous French victory ensured the survival of the Revolution but also kicked off 23 years of perpetual warfare that would not end until the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

The Fatherland in Danger: 1792-93

After Valmy, Brunswick negotiated a retreat and led his Prussian army back into Germany, allowing Dumouriez to go on the offensive and invade the Austrian Netherlands (Belgium). Dumouriez won the Battle of Jemappes (6 November) and occupied Belgium by the end of the year. Elsewhere, French General Adam Philippe de Custine occupied several cities along the Rhine and advanced as far as Frankfurt, while other French armies captured Nice and Savoy. In Paris, the success at Valmy emboldened the National Convention to proclaim a French Republic only a day after the battle, and nationalist fervor continued to grow. Danton announced that it was France's destiny to expand until its borders touched the Rhine.

The French revolutionaries had become so emboldened that they put Louis XVI on trial and executed him on 21 January 1793. This horrified much of Europe, with British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger referring to it as "the foulest and most atrocious act the world has ever seen" (Schama, 687). Britain began mobilizing its armies, but France preempted it by declaring war on Britain and the Dutch Republic in February; Spain, Portugal, and Naples joined the First Coalition around the same time. Dumouriez was ordered to invade Holland but was halted by an Austrian army led by Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld at the Battle of Neerwinden (18 March 1793). Dumouriez's army was soon forced on the defensive and pushed out of the Low Countries altogether; Dumouriez himself defected to the Austrian side on 6 April. Meanwhile, the Prussians had pushed Custine out of the Rhineland and laid siege to French-occupied Mainz (14 April to 23 July).

All this caused alarm in Paris, but the crisis worsened when feuds between various revolutionary factions erupted into civil war. In March 1793, the peasants of the conservative Vendée region rose in revolt after Paris introduced measures of mass conscription; the Vendean rebels took up the royalist cause and formed themselves into the Catholic and Royal Army led by the daring Jacques Cathelineau. In June, several cities rebelled against the extremist Jacobin government in federalist revolts. One federalist city, Toulon, was home to the entire French Mediterranean Fleet, dealing a massive blow to the French war effort when Toulon allowed an Anglo-Spanish fleet into its harbor in August. All this internal strife occurred at a time when the Spanish pushed across the Pyrenees into southern France while Coburg's Austrian army besieged several key fortresses in northeastern France; it seemed only a matter of time before the infant French Republic was strangled in its crib.

Shortly after Dumouriez's treason in April 1793, Danton orchestrated the creation of the Committee of Public Safety, whose job it was to sniff out treason. As the crisis worsened over the course of the summer, the committee accumulated dictatorial powers. By September, it was controlled by a radical faction of Jacobins called the Mountain whose leader, Maximilien Robespierre, ruthlessly hunted down suspected traitors and counterrevolutionaries during the ten-month Reign of Terror. During this time, between 300,000-500,000 French citizens were arrested nationwide; 16,594 of these were guillotined after a trial, 10,000 more died in prison, and thousands of others were killed in extra-judicial massacres. The Revolt of Lyon, for instance, ended in a brutal massacre of the city's federalist rebels while around 10,000 Vendean and Catholic rebels were murdered in the drownings at Nantes.

Notable victims of the Terror included Danton, Brissot, and many other former revolutionary leaders who had become threats to Robespierre's power. However, the defections of Lafayette and Dumouriez led the Committee to keep a tight leash on the armies as well. Jacobin representatives were sent to keep a close eye on generals and to report any signs of treason; even a battlefield defeat could be interpreted as intentional sabotage and result in an execution. Despite his earlier successes, General Custine was guillotined for losing the Rhineland, while General Nicolas Houchard was executed after his win at the Battle of Hondschoote for failing to capitalize on the victory. At least 84 French generals and scores of officers were executed during the Terror; the looming threat of the guillotine gave French armies an extra drive to achieve victory.

Road to Victory (1793-1797)

In August 1793, French war minister Lazare Carnot implemented the levée en masse, which effectively declared total war; every French citizen was expected to contribute in some way to the war effort and all males between 18 and 25 became eligible for conscription. France was able to field 14 armies and around 700,000 troops by September 1794. The French recruits made up for their lack of discipline and training with their revolutionary élan, or fervor; battles were often won by waves of frenzied bayonet charges made by fanatic French troops. By contrast, the nations of the coalition were divided by points of contention elsewhere in Europe, namely the ongoing partitions of Poland, leading to mutual distrust and less effective cooperation.

At the end of 1793, the French won a string of victories against Coburg's Anglo-Dutch-Austrian army at the Battle of Hondschoote (8-9 September) and Battle of Wattignies (15-16 October). After both armies settled into winter quarters, the French launched the next year's campaign with a victory at the Battle of Tourcoing (17-18 May 1794), and at the Battle of Fleurus (26 June). Fleurus marked the final defeat of Coburg's multinational army and was arguably the decisive battle of the war, since afterward the French were constantly victorious. The Catholic and Royal Army was defeated at the Battle of Nantes (14 June 1793) where the royalist hero Cathelineau was killed; afterward the French Republican army traversed the Vendée on a punitive campaign, burning crops and villages, and killing as many as 50,000 Vendeans. The Federalist Revolts were over by the end of 1793, and the French proved victorious at the vital Siege of Toulon, expelling the Anglo-Spanish fleet. This series of French victories negated the need for the dictatorship of the Committee of Public Safety, leading to the fall of Maximilien Robespierre (28 July 1794) and the conservative swing of the Thermidorian Reaction.

Meanwhile, French troops overran Holland in 1795 and established the Batavian Republic as the first of many client states. Prussia and Spain dropped out of the war, and French General Lazare Hoche beat back a landing of British troops and French émigrés at the Battle of Quiberon (23 June to 21 July 1795). However, the highlight of this stage of the war was undoubtedly in Italy, where a 26-year-old Corsican-born general named Napoleon Bonaparte was winning a series of stunning victories against the Austrian army. General Bonaparte had won the love of his troops with his energetic command style, having defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Lodi (10 May 1796), Battle of Arcole (15-17 November 1796), and Battle of Rivoli (14 January 1797). Napoleon's Italian Campaign forced Austria to surrender, signing the Treaty of Campo Formio in October 1797; it also launched the previously unknown Bonaparte into superstardom.

Second Coalition (1798-1802)

By early 1798, every nation had made peace with the French Republic, except for Great Britain. Hoping to break British power in the Mediterranean and win glory for himself in the East, General Bonaparte proposed a military expedition to Egypt; an Egyptian colony would supplement France's struggling treasury and could threaten British power in India. After receiving permission from the Republic's government, the French Directory, Bonaparte sailed for Egypt in June at the head of 38,000 men. He captured the island of Malta before landing at Alexandria, Egypt. Bonaparte then led a march through the Egyptian desert, defeated a Mamluk army at the Battle of the Pyramids (21 July), and captured Cairo.

The French navy that had transported Bonaparte was waiting in Aboukir Bay, where it was attacked by a British fleet under Rear-Admiral Horatio Nelson on 1 August 1798. The ensuing Battle of the Nile resulted in the complete destruction of the French fleet, trapping Bonaparte's army in Egypt. Nelson's victory emboldened France's enemies to form a Second Coalition, this time including Russia, Austria, and Naples (but excluding Prussia, who remained neutral, and Spain, now a French ally). The Austrians won several initial victories in the Rhineland, while a Russo-Austrian force under the celebrated Russian General Alexander Suvorov reclaimed much of northern Italy. The French reacted to this threat by implementing mass conscription again.

Meanwhile, Bonaparte had been defeated by an Anglo-Ottoman force at the Siege of Acre (1799). Abandoning his army in Alexandria, he returned to France where he seized power in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and ended the French Revolution. Now serving as First Consul of the French Republic, Bonaparte led an army across the Alps and into Italy, where he won a major victory over the Austrians at the Battle of Marengo (14 June 1800). Austrian military power was further broken by the French victories at the Second Battle of Zurich (25-26 September 1799) and the Battle of Hohenlinden (3 December 1800).

As the French began winning, the Second Coalition fell apart. Tsar Paul I of Russia had fallen out with his allies and pulled Russia out of the war in 1800. Paul became angered when British ships started seizing neutral shipping as part of Britain's blockade against France; in response, the tsar formed a League of Armed Neutrality. Consisting of Denmark, Sweden, Prussia, and Russia, the league threatened Britain with war should attacks on neutral ships continue. Paul also entered into talks with France about a potential Franco-Russian alliance but was assassinated in March 1801. His League of Armed Neutrality fell apart a month later when the British destroyed the Danish fleet at the First Battle of Copenhagen (2 April).

Peace of Amiens

In 1801, Austria signed the Treaty of Lunéville and exited the war, confirming France's territorial gains in Italy. The British were initially determined to keep fighting and defeated the remnants of Bonaparte's Egyptian army at the Battle of Alexandria (21 March 1801), capturing the city six months later. However, Britain eventually came to terms with France, making peace with the Treaty of Amiens (25 March 1802). Though the treaty would last for only a year, it marked an end to the Revolutionary Wars. The following series of conflicts, beginning in May 1803 and ending in June 1815, comprise the Napoleonic Wars.

At the end of the Revolutionary Wars, France controlled the Low Countries, the left bank of the Rhine, and almost all of Italy. It had created several sister republics including the Batavian Republic (Holland), Cisalpine Republic (northern Italy), and Helvetic Republic (Switzerland), among others; after the coronation of Napoleon I as Emperor of the French in 1804, these republics were either transformed into client kingdoms or incorporated directly into the French Empire.

Other Conflicts

Several other conflicts were related to the Revolutionary Wars. For instance, the slaves of the French colony of Saint-Domingue were inspired by the ideals of the French Revolution to revolt against their masters in 1791. This blossomed into the Haitian Revolution, as former slaves successfully fended off multiple European invasions. After twelve years of bloodshed, Haiti finally won its independence in 1804, the only time a nation has been founded by a slave revolt.

Another related conflict was the Quasi-War (1798-1800) between France and the United States, which began after the United States refused to repay French loans taken out during the American War of Independence (1775-1783). This led to a series of engagements between individual French and American ships. The war, which marked one of the first tests of the American Navy, fizzled out when diplomatic negotiations resulted in peace at the Convention of 1800. The restoration of good Franco-American relations paved the way for the Louisiana Purchase (1803).