Frigg is a fertility goddess in Norse mythology. She is the wife of Odin, king of the gods, and is the greatest goddess of the Norse pantheon. She is thought to have developed, along with the goddess Freyja, from an earlier fertility deity. Friday (Frigga’s Day) is named in her honor.

She is thought to have originally been known in German Mythology as Frija ("beloved") who then became both Frigg and Freyja in Norse Mythology (though this claim has been challenged). In the 8th-century CE work, The Origin of the Lombards by Paul the Deacon, she is known as Freia, Odin’s wife, who helps the Lombards win their decisive military victory and is responsible for their name. She is also known as Hiln (though this is sometimes her daughter or her messenger), Frigga, Frea, and Fria.

Her primary attributes are clairvoyance, cleverness, and prophecy, and she was known as the goddess of marriage and motherhood. Frigg was the mother of Baldr, god of wisdom and beauty, and the blind god Hodr, who is tricked by the mischievous Loki into killing his brother. Contrary to the assertions of some writers, she is not the mother of Thor, Odin’s son, who is Baldr’s half-brother. The death of Baldr (also given as Baldur) is among the few tales featuring Frigg at any length since, even though she is regularly referenced as a powerful goddess who knows the fate of all, she does not appear in many tales except, sometimes, as a peripheral figure. She was a völva (seeress), however, and seems to have been popular in divination rites.

The Norse religion was the last of the pagan belief systems to fall to Christianity, and Frigg, for all her power and popularity, was replaced by Christian tales along with all the other Norse deities. She has experienced a revival of interest in the last 50 years, however, through the efforts of the Wiccan and Neo-Pagan movements. Many people, especially women, devote themselves to Frigg as their deity of choice just as they did in ancient times.

Possible Origin & Freyja Link

Around 400-700 CE, when Germanic tribes were migrating between regions, their groups were led by a chieftain and his wife (often believed to have supernatural powers of seeing the future/knowing people’s fate) who were reflected in the veneration of the powerful god Odr and his seeress wife Frija. The divine couple of Germanic myth are believed, by some scholars, to have become Odin and Frigg in Norse mythology.

Her development and final form would be simple enough to follow if that were the end of the story, but there is also the better-known goddess Freyja to be considered who shares many of the same attributes. Frigg is a member of the Aesir – the gods who live in Asgard – while Freyja of the Vanir – the deities who live in Vanaheim – but that is one of the biggest differences. Both are associated with fertility, but Frigg is considered more promiscuous than Freyja – even though there does not seem to be much evidence to suggest this – and enjoys a higher status as Odin’s wife.

Frigg is also said to live in her own realm – Fensalir – whose location is never given, while Freyja is firmly associated with both Asgard and Vanaheim but also presides over her own afterlife realm, Folkvangr ("field of the people") said to be a mirror of the beautiful Vanaheim. It is likely that the goddess was first envisioned by Germanic peoples and then reimagined first as Freyja by the Norse before they also adopted Frigg. This would account for Frigg’s name being more widely known outside of Scandinavia than Freyja’s and for Freyja featuring in more stories than Frigg in Norse mythology.

Any discussion of the Frigg/Freyja connection is ultimately speculative, however, as Norse religion was passed down orally for centuries and the written versions of the tales now extant were all composed during the Christian era. Without primary sources, there is no way of knowing which goddess came first or what earlier goddesses might have influenced their development. It has also been proposed, based on ancient Norse artwork, that the two goddesses developed at the same time independently, though this seems unlikely as their attributes mirror each other closely.

Wagers with Odin

Both goddesses have an easy relationship with Odin characterized by his obvious respect for them and their ability to deceive him, often in sport, though sometimes to further an agenda. In these tales, Frigg is depicted as a clever woman who can outwit Odin, god of wisdom, to get her own way, reflecting the relatively high status women enjoyed in Norse culture.

In the 7th-century work Origo Gentis Langobardorum (“Origin of the Tribe of the Lombards”) and Paul the Deacon’s 8th-century work drawn from it, Frigg is featured as the goddess who not only elevates the Lombards to victory but is responsible for their name. In this story, the Lombards – then a small Scandinavian tribe known as the Winnili – received demands from the powerful Vandals that they should submit themselves as vassals and pay tribute or prepare for war. The Winnili sent back word that they would rather die as free men than live as slaves.

Both the Vandals and the Winnili then appealed to Odin for victory. Odin favored the Vandals while Frigg sided with the Winnili. Not wanting to upset his wife, Odin replied that victory would be given to whichever side he saw first at dawn of the next day, which he was sure would be the Vandals. The völva Gambara of the Winnili appealed to Frigg (given as Freia in the story) to grant victory to her sons in battle and Frigg told Gambara to return to her tribe and have all of the women take down their hair, arrange it across their faces to look like beards, and stand with their men in the field where Odin would see them first when he rose in the morning and looked to the east.

Gambara did as she was told and, the next morning, all the women stood in ranks with the men, their hair tied across their faces and braided to look like beards. Odin looked out his window and said to Frigg, "Who are these long-beards?" to which Frigg replied that, since he had now given them their name, he should also give them victory. Odin agreed, and the 'Longbeards' became the Lombards who defeated the Vandals and kept their autonomy.

In the 13th-century work Grímnismál ("The Lay of Grimnir") from the Poetic Edda, Frigg also manipulates Odin, this time over a perceived insult he gave to her foster-son. In this tale, two young sons of a great king, Geirröth and Agnarr, go fishing but are blown out to sea by a storm. They are taken in by a peasant and his wife who raise them. The peasant fosters Geirröth while his wife tends to Agnarr. When the boys are grown, the couple sends them back to their kingdom. Upon reaching the shore, Geirröth kicks the boat back out to sea, telling Agnarr to fend for himself, and returns to the palace where he finds their father has died and he is now king.

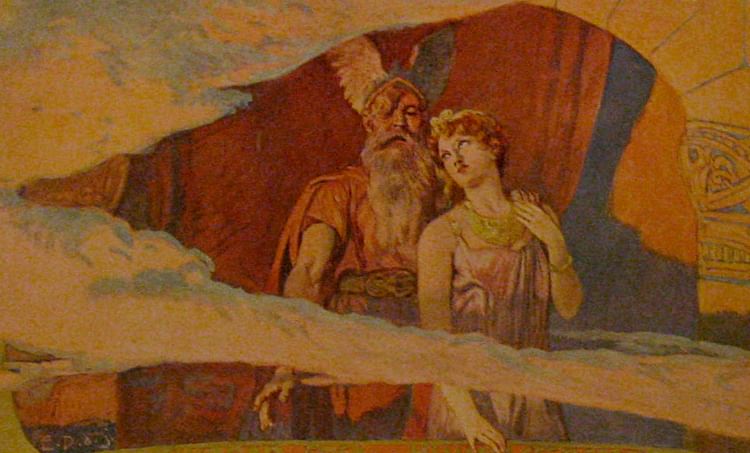

The scene switches to Odin and Frigg who are sitting in Odin’s throne room from which they can see all the Nine Realms. The peasant and his wife, it turns out, were actually Odin and Frigg, and Odin casually observes how his boy has become a powerful king while hers is a nothing now living in a cave with a giantess as a mate. Frigg replies that Geirröth is so cheap and inhospitable he tortures his guests if he feels there are too many mooching off him. Odin challenges her to a wager, saying he will go disguised as a traveler named Grímnir and will no doubt be treated well. Frigg accepts the bet and then sends her handmaiden, Fulla, to warn Geirröth that a wizard is coming to bewitch him and he will know the man because not even the bravest dogs will dare attack him.

Odin arrives at Geirröth's castle and, as foretold, the dogs will not so much as bark at him, and so he has the man arrested. The traveler will only say his name and nothing else and so Geirröth has him bound and set between two fires for eight nights. On the 9th night, Geirröth's son, Agnarr, feeling bad for the stranger, brings him a horn of ale. Grímnir thanks him by telling him that his father will soon be dead and he, Agnarr, will be king of the Goths. Grímnir then reveals himself as Odin, and Geirröth, hastening to cut the bonds and free his guest, slips and falls on his sword, killing himself.

Infidelity & Manipulation

Although Geirröth was never inhospitable prior to this, Frigg 'proves' that he was and so wins the wager. This is not the only time Frigg purposefully deceives Odin to get her way. In Book I of the 12th-century work Gesta Danorum ("Deeds of the Danes") by Saxo Grammaticus, Odin goes away on a journey, and Frigg, wanting the gold that adorns his statue, sleeps with a slave in return for his help in toppling the figure of Odin and bringing her its gold. She keeps this a secret from Odin, but he discovers she was behind the vandalism and theft and imposes exile upon himself in shame for having such a wife.

In the 13th-century Ynglinga Saga, Odin is again away from home on journeys and his brothers Vili and Vé are left to rule in his place. Finally believing Odin is either dead or simply never going to return, they divide his possessions and take turns sleeping with Frigg. She keeps this information from Odin upon his return, but he discovers this infidelity as well. Loki alludes to both in the poem Lokasenna ("Loki’s Taunts") of the Poetic Edda when he insults Frigg by publicly revealing she slept with both of Odin’s brothers. Frigg is defended by Freyja in the Lokasenna who tells him to be careful how he treats the queen because she knows the fate of all beings and is more powerful than she appears. In these stories, she does seem to be just as Freyja describes her, but in the tale of the Death of Baldr, all her power and manipulative skills fail her.

Death of Baldr

In Section 49 of the 13th-century Gylfaginning of the Prose Edda, Frigg is tormented by dreams in which a tragedy – that she cannot see – takes her son Baldr. At this same time, Baldr himself has had some similar dreams. Since Frigg knows the fate of all, but cannot see what is coming for Baldr, she becomes upset and so Odin travels to the realm of Hel, raises the spirit of a witch, and asks her. The witch only tells him that Hel has been prepared for Baldr's arrival. Frigg then goes throughout the Nine Realms of Norse cosmology extracting from all things animate and inanimate the promise that they will not harm her son. Afterwards, the gods of Asgard take up the sport of hurling objects at Baldr which, because of their promise to Frigg, bounce harmlessly off the god.

Loki, observing this, transforms himself into a woman and goes to visit Frigg on her throne in Fensalir. She asks the visitor what the gods are up to in Asgard and is told they are playing at their usual sport throwing things at Baldr, and then the visitor asks if it is true that all things took the oath never to harm the most handsome and kindest of the gods. Frigg, suspecting nothing, tells the woman that she never extracted an oath from the young plant mistletoe because it was so small and harmless.

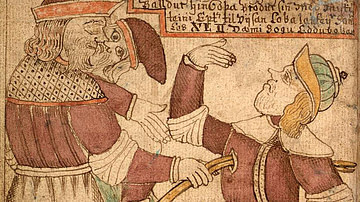

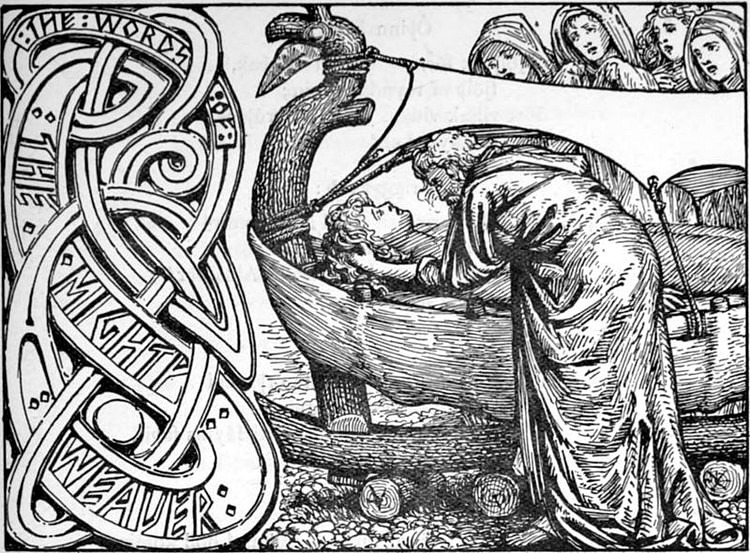

Loki leaves and finds the mistletoe west of Valhalla. Fashioning it into a small projectile, he then returns to Asgard and hands it to the blind god Hodr (Höðr) who was feeling bad because he was unable to participate in the game. Loki assures him that he will guide Hodr’s aim and Hodr hurls the mistletoe which pierces Baldr’s breast, killing him. The gods are all struck with horror and begin weeping as Frigg arrives to find her son dead. She asks for a volunteer to journey to the afterlife realm of Hel and ask for the return of Baldr’s soul and then prepares a grand funeral for him. At this ceremony, Baldr’s wife, Nanna, the moon goddess, kills herself in grief.

Hermóðr, referenced as Baldr’s brother but not as Frigg’s son, volunteers for the journey to Hel as he is the messenger god and used to hard journeys. He arrives at the dark realm below the misty land of Niflheim and asks the goddess Hel for the return of Baldr and Nanna. Hel agrees on one condition: all things, living and dead, must weep for Baldr. The spirits of Baldr and Nanna give Hermóðr gifts for Odin, Frigg, and Fulla, and he departs on his mission to have all things mourn Baldr with their tears. He is almost successful, but when he encounters a giantess named Thokk, living in a dark cave, she refuses, noting that the dead should remain with the dead. Thokk is actually Loki in another of his forms, but because she will not weep, Baldr and Nanna remain in Hel and Frigg is left to mourn her son for the rest of her life.

Conclusion

In the stories of her wagers with Odin, her infidelities, and her attempts to save her son, as well as her powers of divination, Frigg represents the female experience of the Norse culture in which women were recognized as autonomous individuals capable of many – if not all – of the same sorts of behavior as men. Frigg is never depicted as secondary to Odin or to any of the other deities of the pantheon, and for that matter, neither is Freyja or the other goddesses. Even a minor deity such as Fulla is suggested as a completely realized character with her own wants and needs.

Although, as a fertility goddess, Frigg’s primary responsibility was arranging matches for marriage, she is almost never referenced as engaging in this activity. The stories in which she features fully always show her as either Odin’s companion and intellectual equal – or better – or as a devoted mother looking out for her children. Her powers of second sight are often referenced but fail her when they could have done her the most good, exemplifying the futility of even the best of mothers in trying to keep their child safe from the dangers of the world. Further, she is among the few deities to survive Ragnarök, the Twilight of the Gods, which destroys the Nine Realms and during which Odin is killed by the wolf Fenrir, and so she exemplifies the grieving widow as well as the mourning mother, a role many women in the Viking Age would have been able to easily identify with.

In all her stories, Frigg is a completely independent woman – even seeming to live apart from her husband in her own land with her own palace – and her popularity no doubt derived, at least in part, from this aspect of her personality. Although Norse religion emphasized the inevitability of fate in a person’s life, what one did between birth and death was up to the individual, and a strong will and independent spirit were highly valued in both men and women.

Frigg never had a temple (or at least one has never been discovered) but seems to have been honored by the mortal völva of any village as their inspiration and source of power in divining the future. Throughout the Viking Age of c. 790 - c. 1100, Frigg held her place as one of the most beloved among the Norse deities but, after the Norman conquest of England in 1066 and the triumph of Christianity over Norse belief, she began to fade, and her worship was replaced by the figure of the Virgin Mary, dutiful handmaiden of the Christian God, and the independent Frigg was forgotten until her recent revival by the Neo-Pagan and Wiccan movements.