Frodi (Old Icelandic: Fróði) is the name of legendary Danish kings in Norse mythology. There is a whole range of kings bearing the same name, pointing to fascinating traditions in both Old Icelandic and continental Germanic storytelling. Frodi features in Snorri Sturluson's Skáldskaparmál, the Ynglinga saga, and Saxo Grammaticus' Gesta Danorum, among other sources.

The Golden Age of Frodi in the Skáldskaparmál

In his Skáldskaparmál, part of the Prose Edda, the 13th-century Icelandic chieftain and author Snorri Sturluson explains the origins of many complex metaphors or kenningar. He mentions that one of the terms for gold is the flour of Frodi (Old Icelandic: Fróði), elsewhere the meal of Frodi, and goes on to explain the origin of this metaphor, where he fancifully links Odin to the history of Denmark and partly Sweden. Thus, in Snorri's story, a son of Odin, Skjöld, the founder of the dynasty, had a son, Fridleif, who in turn has a son Frodi. Chronologically, this would have been during the reign of Roman emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE) and his pax romana. There are some historical elements to this, such as trade between Romans and proto-Danish speakers, with members of the aristocracy forging their prestige through contact with the Roman Empire, but a great unified land certainly did not exist.

Snorri tries to draw a parallel to Jesus Christ in what he tells next, and he also tries to prove how naive pre-Christians were in that they attributed the peace reigning in all northern territories at the time to Frodi. We have a bit from the myth of a golden era, with no murders or thefts. Frodi meets King Fjölnir from Sweden, and he purchases two slave women at the same time two gigantic millstones are discovered, which have the ability to grind anything. So Frodi tells the slaves to grind gold and prosperity and gives them very short breaks, only as long as a song, which is why they name the poem they are chanting Grottasöngr, after the name of the magic mill. The maidens deplore the inability of the king to foresee the consequences of his deeds, because what they in fact ground is an army against Frodi. A sea king called Mysing comes, plunders, and kills Frodi. Mysing orders them to grind salt, which they do until the ships sink, the seas flow into the mill hole, and they become salt.

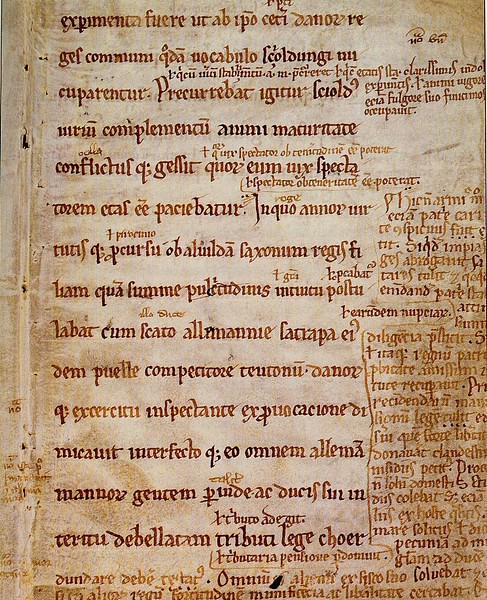

Snorri probably got these very precise details from the Grottasöngr of the Poetic Edda, which he cites after retelling this story. In the poem, it is revealed that the girls are descendants of mountain giants, and they are the ones who had shaped the grindstone, but Frodi remains ignorant of their lineage, thus losing his seat at Hleidra (Lejre). So, historically, there might have been a reference to the first leaders here; Lejre (also bearing the name Fredshøj or Peace Barrow) had settlements dating back to 500. Dated to c. 650, the remains of a princely burial were excavated down by the river in a barrow called Grydehøj. The man and his grave goods had been cremated, but a profusion of melted bronze and gold, as well as sacrificed animals testify to his wealth. Snorri, however, interprets it from a Christian temporal and mythical perspective. Most probably, it was a saga of the Skjöldungs from which Snorri adopted this notion, as suggested by a 17th-century paraphrase.

The Peace of Frodi in the Ynglinga Saga

This is not the only Frodi we know about. In the Ynglinga saga (the first saga from the cycle Heimskringla, the history of the kings of Norway), Snorri links the peace of Frodi to the god Freyr, interpreted here as the king of Sweden succeeding Njörd (Njörðr), succeeding Odin himself, with Freyr and Njörd being members of the Vanir family of gods in Old Icelandic sources, deities linked to fertility. Sometimes he goes back to considering these gods divinities, not only people turned divine, for example, when he states that in times of prosperity Swedes thank Freyr, and the wealthier people get, the more they worship him than other gods. This happens in chapter 10, where Snorri seems to mix Freyr and Frodi because while he speaks of the peace of Frodi, he insists that the Sviar attribute it to Freyr, also called Yngvi, his descendants being the famous Ynglingar.

After his death, he was carried secretly into the tomb, and the people were told for three years that he was still alive, pouring gold, silver, and copper through the windows of his mound. Even after people found out the truth, the prosperity would continue as long as they sacrificed to him. In chapter 11, however, Snorri does place Frodi in Lejre (Hleidra), calling him peace-Frodi, while Fjölnir, son of Freyr, resides in Uppsala. According to a poet named Thjodolf of Hvinir, who also wrote a poem to King Rögnvald of Vestfold tracing his lineage back to the Ynglingar (Ynglingatal), Frodi set up a huge vat of mead in his hall, and upon visiting him, Fjölnir got so drunk that he fell into it and drowned. This reveals it was very important for kings to have their power legitimized by association with these legendary clans.

There are also more obscure mentions of a Frodi, son of Danr, or son of Harald Fairhair, but all in all, it is very likely that these two characters, Freyr and Frodi were based on a local deity split into several versions and then turned into legendary historical characters. This finds some justification in the poem Skírnismál, where Frey himself is called "fróði", meaning the wise or the prosperous one, and also in the manuscript Flateyjarbók, where Swedes ascribed a golden age to Freyr, and Danes to Frodi.

Gesta Danorum

Another source mentioning Frodi is a skaldic poem from the 10th century, written by Einarr Skálaglamm in honour of Haakon jarl, stating that no ruler had brought such fruitfulness and peace like Frodi. We encounter traces of this tradition in the 12th-century Gesta Danorum by Saxo Grammaticus as well – several kings in fact – adding to the confusion. In Saxo Grammaticus' account, Frotho I succeeds his father Hadingus, an early legendary Danish king, he invigorates the treasury and slays a dragon, as well as campaigns in the Baltic or expeditions against the Frisians, the Scots, and the English.

There has been an attempt to identify him with a namesake Viking leader of the 9th century, who established himself in Dublin (Ellis Davidson, 37), but the evidence is flimsy. More likely, we are dealing with a forgotten Danish leader who may have indeed travelled as far as Russia and perhaps raised hill forts along the western Dvina. Other elements of the story may well have been influenced by more general Germanic themes, with dragon-slaying playing a part in both the Saga of the Völsungs and the Saga of Ragnar Lodbrok.

Frotho III bears the best resemblance to the Ynglinga saga. Frodi, son of Fridleif, is well-known for his law-giving. After defeating his enemies, peace reigns in his kingdom, and Saxo mentions the same example of good governance, the king leaving out a gold arm ring that no one dares to steal. His fame and authority coincide with the life of Christ, but this ends when a woman eggs her son to steal the ring. Trying to hide from his wrath, she turns into a sea cow and mauls him. For fear of a revolt, the Danes hide away Frodi's body in a cart they carry around for as long as three years – this reminds a bit of Nerthus mentioned by Tacitus in Germania – during which prosperity continues. The same event happens in Ynglinga saga. So from these sources, we can infer that Frodi definitely had something to do with a fertility cult, a remnant of the cult of the Vanir gods, historicized by later Christian authors.

Saxo's book V, the lengthiest, in fact, only deals with this particular character, where he describes how he established a truly northern empire, drawing on Icelandic traditions in constructing the character. He does not begin his career heroically, though, deceived by the sons of Vestmar, who turn the court into a centre of corruption. He eventually establishes himself as king – again a topos of heroic tradition – yet the way he succeeds makes his story unique. He is rescued from death at sea by a Norwegian youth named Erik, who would become his follower and assist him in his exploits – an idea most probably modelled after the partnership between Valdemar I and Absalon, Saxo's patron (Ellis Davidson, 114) and reflecting the achievements of Danish politics in the 12th century in the East. Saxo attempted to conjure up a glorious past for Denmark by freely blending stories from lots of sources so that Frodi (Frotho) can emerge as this larger-than-life semi-legendary leader, who defeated a Slavic invasion, dispersed an army of Huns, got involved in Swedish power struggles, invaded Norway, mustered vessels to conquer Britain, and escaped from a burning hall, just to name some of his many Viking feats.

This Frodi version has also been interpreted as an instance of the "summer king" motif, related to the myths of the Vanir. The summer king's name is linked to his function, he leads a military expedition to a colder land where he encounters a winter king, a marriage with his daughter follows, but the relationship is tense, and the king dies because of a curse; his death is symbolic for either barrenness or prosperity. Saxo's Frotho meets some of the characteristics with his pursuing Hanunda, daughter of the Huns' king, and Alvilda, daughter of Gøtarus, a Norwegian king, the incitement of a sorceress, the punishment of her son for stealing the gold arm ring from the post – symbolising the rule of law – or his death after which his subjects carry his body in a wagon and eventually bury him near a river. His son's name Fridlevus, "remnant of peace", suggests a continuation of Frodi's peace.

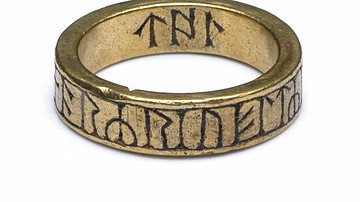

From Frodi to Frodo

The Latinized version of the name was used by Tolkien in Lord of the Rings. But how much does Frodo have in common with a series of legendary kings by the name of Frodi? We could find a connection in the etymology itself, wisdom by experience. Through his whole journey, Frodo gains the ability to fight evil while being tempted by evil. The story can be interpreted as a restoration of peace and welfare in Middle Earth, but the Christian aspect should not be overlooked either. If we consider Frodo's suffering and tragedy in his role as the ringbearer, it can serve as an analogy with the sin-bearing of Jesus Christ. His journey to Mount Doom and subsequent destruction of the ring and Sauron may have less in common with the Norse tradition and more with Christ's carrying the cross to Calvary.