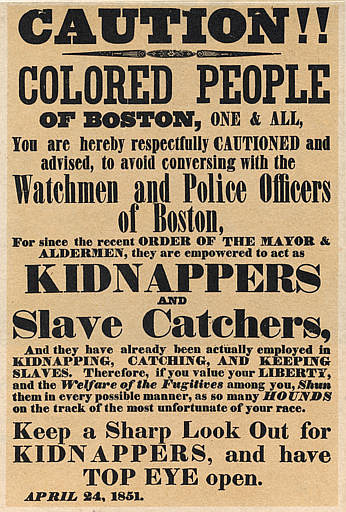

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 (1850-1864) was part of the Compromise of 1850, drafted to diffuse tensions between Southern 'slave states' and Northern 'free states.' The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 already allowed slaveholders to reclaim their fugitive slaves from Northern states, but, since many Northerners were not inclined to help them in this, the 1793 law had little real power. Although one could be punished for not complying with the 1793 law, Northern police officers could refuse to make an arrest, and Northern judges could dismiss a case, as many saw the 'law' as legalized kidnapping. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 compelled Northern authorities, law enforcement, and ordinary citizens to report on fugitives and help slave catchers retrieve them.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 (as with the law of 1793) was extremely unpopular in the North. People who had never had to give much thought to the issue of slavery were now being forced to participate in it or face six months in prison and a fine of $1,000.00 (roughly $37,000.00 today). Many people in the North continued to shelter and help fugitive slaves (freedom seekers), and some, like Harriet Tubman (circa 1822-1913), took direct action in challenging the law.

In spring 1860, while visiting a cousin in Troy, New York, Tubman heard that a freedom seeker named Charles Nalle had been found by his master (who was also his brother) and would be deported back to the South. Tubman instantly took action, and her dramatic rescue of Nalle has become one of the best-known from her days as a conductor on the Underground Railroad. The response of the crowd supporting Tubman's rescue is also famous as a clear example of Northern resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was one of the five bills introduced by Senator Stephen A. Douglas (1813-1861) as the Compromise of 1850. Douglas' legislation was a reworking of an earlier compromise introduced by Senator Henry Clay (1777-1852) of Kentucky. Douglas' version streamlined Clay's original eight resolutions down to five bills, all to be voted on separately, and these were passed by the US Congress in 1850. Section 3 of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 addresses the responsibilities of authorities and law enforcement in apprehending freedom seekers, while Section 7 gives notice to citizens of Northern states what was expected of them and the punishment they would suffer for non-compliance:

And be it further enacted, That any person who shall knowingly and willingly obstruct, hinder, or prevent such claimant, his agent or attorney, or any person or persons lawfully assisting him, her, or them, from arresting such a fugitive from service or labor, either with or without process as aforesaid, or shall rescue, or attempt to rescue, such fugitive from service or labor, from the custody of such claimant, his or her agent or attorney, or other person or persons lawfully assisting as aforesaid, when so arrested, pursuant to the authority herein given and declared; or shall aid, abet, or assist such person so owing service or labor as aforesaid, directly or indirectly, to escape from such claimant, his agent or attorney, or other person or persons legally authorized as aforesaid; or shall harbor or conceal such fugitive, so as to prevent the discovery and arrest of such person, after notice or knowledge of the fact that such person was a fugitive from service or labor as aforesaid, shall, for either of said offences, be subject to a fine not exceeding one thousand dollars, and imprisonment not exceeding six months, by indictment and conviction before the District Court of the United States for the district in which such offence may have been committed, or before the proper court of criminal jurisdiction, if committed within any one of the organized Territories of the United States; and shall moreover forfeit and pay, by way of civil damages to the party injured by such illegal conduct, the sum of one thousand dollars for each fugitive so lost as aforesaid, to be recovered by action of debt, in any of the District or Territorial Courts aforesaid, within whose jurisdiction the said offence may have been committed.

(American Battlefield Trust, Section 7)

The Federal Government of the United States was now actively engaged in slave-catching, which, to many in the North, it had no business participating in. Once the Act was signed into law, however, even those actively opposed to slavery were expected to support it, creating an atmosphere of hostility and fear that further polarized the free and slave states, escalating tension in the years leading up to the American Civil War, as scholar Andrew Delbanco notes:

It was an act without mercy. To those arrested under its authority, it denied the most basic right enshrined in the Anglo-American legal tradition: habeas corpus – the right to challenge, in open court, the legality of their detention. It forbade defendants to testify in their own defense. It ruled out trial by jury. Except for proof of freedom, such as emancipation papers signed by a former owner, the Fugitive Slave Act disallowed all forms of exonerating evidence, including evidence of beatings, rape, or other forms of abusee while the defendant had been enslaved.

It criminalized the act of sheltering a fugitive and required local authorities to assist the claimant in recovering his lost human property…Everything about the Fugitive Slave Act favored the slave owners. Even free black people in the North – including those who had never been enslaved – found their lives infused with the terror of being seized and deported on the pretext that they had once belonged to someone in the South.

(5)

Even so, many abolitionists defied the law – such as William Still (1819-1902) and Passmore Williamson (1822-1895), who, in 1855, participated in the liberation of Jane Johnson and her two children in Philadelphia. Harriet Tubman, as seen below, also refused to comply with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, and, as noted, so did the crowd she assembled to help her in freeing Charles Nalle in Troy, New York, in 1860.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 remained on the books until it was repealed in June 1864, toward the end of the American Civil War (1861-1865). In 1865, slavery was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment.

Text

The following excerpt is taken from Harriet, The Moses of her People (1886) by Sarah Hopkins Bradford as given on the site Documenting the American South, pp. 119-128.

In the spring of 1860, Harriet Tubman was requested by Mr. Gerrit Smith to go to Boston to attend a large Anti-Slavery meeting. On her way, she stopped at Troy to visit a cousin, and while there the colored people were one day startled with the intelligence that a fugitive slave, by the name of Charles Nalle, had been followed by his master (who was his younger brother, and not one grain whiter than he), and that he was already in the hands of the officers, and was to be taken back to the South.

The instant Harriet heard the news, she started for the office of the United States Commissioner, scattering the tidings as she went. An excited crowd was gathered about the office, through which Harriet forced her way, and rushed up stairs to the door of the room where the fugitive was detained.

A wagon was already waiting before the door to carry off the man, but the crowd was even then so great, and in such a state of excitement, that the officers did not dare to bring the man down. On the opposite side of the street stood the colored people, watching the window where they could see Harriet's sunbonnet, and feeling assured that so long as she stood there, the fugitive was still in the office. Time passed on, and he did not appear. "They've taken him out another way, depend upon that," said some of the colored people. "No," replied others, "there stands 'Moses' yet, and as long as she is there, he is safe."

Harriet, now seeing the necessity for a tremendous effort for his rescue, sent out some little boys to cry fire. The bells rang, the crowd increased, till the whole street was a dense mass of people. Again and again the officers came out to try and clear the stairs, and make a way to take their captive down; others were driven down, but Harriet stood her ground, her head bent and her arms folded. "Come, old woman, you must get out of this," said one of the officers; "I must have the way cleared; if you can't get down alone, someone will help you."

Harriet, still putting on a greater appearance of decrepitude, twitched away from him, and kept her place. Offers were made to buy Charles from his master, who at first agreed to take twelve hundred dollars for him; but when this was subscribed, he immediately raised the price to fifteen hundred. The crowd grew more excited. A gentleman raised a window and called out, "Two hundred dollars for his rescue, but not one cent to his master!"

This was responded to by a roar of satisfaction from the crowd below. At length the officers appeared, and announced to the crowd, that if they would open a lane to the wagon, they would promise to bring the man down the front way.

The lane was opened, and the man was brought out – a tall, handsome, intelligent white man, with his wrists manacled together, walking between the U.S. Marshal and another officer, and behind him his brother and his master, so like him that one could hardly be told from the other.

The moment they appeared, Harriet roused from her stooping posture, threw up a window, and cried to her friends: "Here he comes – take him!" and then darted down the stairs like a wild-cat. She seized one officer and pulled him down, then another, and tore him away from the man; and keeping her arms about the slave, she cried to her friends: "Drag us out! Drag him to the river! Drown him! but don't let them have him!"

They were knocked down together, and while down, she tore off her sunbonnet and tied it on the head of the fugitive. When he rose, only his head could be seen, and amid the surging mass of people the slave was no longer recognized, while the master appeared like the slave.

Again and again, they were knocked down, the poor slave utterly helpless, with his manacled wrists, streaming with blood. Harriet's outer clothes were torn from her, and even her stout shoes were pulled from her feet, yet she never relinquished her hold of the man, till she had dragged him to the river, where he was tumbled into a boat, Harriet following in a ferryboat to the other side.

But the telegraph was ahead of them, and as soon as they landed, he was seized and hurried from her sight. After a time, some school children came hurrying along, and to her anxious inquiries they answered, "He is up in that house, in the third story." Harriet rushed up to the place. Some men were attempting to make their way up the stairs. The officers were firing down, and two men were lying on the stairs, who had been shot.

Over their bodies our heroine rushed, and, with the help of others, burst open the door of the room, and dragged out the fugitive, whom Harriet carried downstairs in her arms. A gentleman who was riding by with a fine horse, stopped to ask what the disturbance meant; and on hearing the story, his sympathies seemed to be thoroughly aroused; he sprang from his wagon, calling out, "That is a blood-horse, drive him till he drops." The poor man was hurried in; some of his friends jumped in after him and drove at the most rapid rate to Schenectady.

This is the story Harriet told to the writer. By some persons it seemed too wonderful for belief, and an attempt was made to corroborate it. Rev. Henry Fowler, who was at the time at Saratoga, kindly volunteered to go to Troy and ascertain the facts.

His report was, that he had had a long interview with Mr. Townsend, who acted during the trial as counsel for the slave, that he had given him a "rich narration," which he would write out the next week for this little book. But before he was to begin his generous labor, and while engaged in some kind efforts for the prisoners at Auburn, he was stricken down by the heat of the sun and was for a long time debarred from labor.

This good man died not long after and the promised narration was never written, but a statement by Mr. Townsend was sent me, which I copy here:

Statements made by Martin I. Townsend, Esq., of Troy, who was counsel for the fugitive, Charles Nalle.

Nalle is an octoroon; his wife has the same infusion of Caucasian blood. She was the daughter of her master, and had, with her sister, been bred by him in his family, as his own child. When the father died, both of these daughters were married and had large families of children. Under the highly Christian national laws of "Old Virginny," these children were the slaves of their grandfather. The old man died, leaving a will, whereby he manumitted his daughters and their children, and provided for the purchase of the freedom of their husbands.

The manumission of the children and grandchildren took effect; but the estate was insufficient to purchase the husbands of his daughters, and the fathers of his grandchildren. The manumitted, by another Christian, "conservative," and "national" provision of law, were forced to leave the State, while the slave husbands remained in slavery.

Nalle, and his brother-in-law, were allowed for a while to visit their families outside Virginia about once a year but were at length ordered to provide themselves with new wives, as they would be allowed to visit their former ones no more. It was after this that Nalle and his brother- in-law started for the land of freedom, guided by the steady light of the north star. Thank God, neither family now need fear any earthly master or the bay of the bloodhound dogging their fugitive steps.

Nalle returned to Troy with his family about July 1860 and resided with them there for more than seven years. They are all now residents of the city of Washington, D. C. Nalle and his family are persons of refined manners, and of the highest respectability. Several of his children are red- haired, and a stranger would discover no trace of African blood in their complexions or features. It was the head of this family whom H. F. Averill proposed to doom to return less exile and life-long slavery.

When Nalle was brought from Commissioner Beach's office into the street, Harriet Tubman, who had been standing with the excited crowds rushed amongst the foremost to Nalle and running one of her arms around his manacled arm, held on to him without ever loosening her hold through the more than half-hour's struggle to Judge Gould's office, and from Judge Gould's office to the dock, where Nalle's liberation was accomplished. In the mêlée she was repeatedly beaten over the head with policemen's clubs, but she never for a moment released her hold, but cheered Nalle and his friends with her voice, and struggled with the officers until they were literally worn out with their exertions, and Nalle was separated from them.

True, she had strong and earnest helpers in her struggle, some of whom had white faces as well as human hearts, and are now in Heaven. But she exposed herself to the fury of the sympathizers with slavery, without fear, and suffered their blows without flinching. Harriet crossed the river with the crowd, in the ferryboat, and when the men who led the assault upon the door of Judge Stewart's office were stricken down, Harriet and a number of other colored women rushed over their bodies, brought Nalle out, and putting him in the first wagon passing, started him for the West.

A lively team, driven by a colored man, was immediately sent on to relieve the other, and Nalle was seen about Troy no more until he returned a free man by purchase from his master. Harriet also disappeared, and the crowd dispersed. How she came to be in Troy that day, is entirely unknown to our citizens; and where she hid herself after the rescue, is equally a mystery. But her struggle was in the sight of a thousand, perhaps of five thousand spectators.