Gabriel's Rebellion (30 August 1800) was a carefully planned slave revolt in Virginia orchestrated by the literate slave blacksmith Gabriel (l. c. 1776-1800), property of one Thomas Prosser, and so referred to as Gabriel Prosser. The plans for the revolt were betrayed before it could be set in motion, and Gabriel and his supporters were hanged.

Gabriel's Rebellion terrified the White population because the plans laid were so extensive – with a goal of nothing less than the freedom of all enslaved Black people in slave-holding states, starting with Virginia – and the deaths of all White people who opposed liberation and supported slavery. The plan was to take the arsenal at Richmond, Virginia, equip an army of slaves, take Governor James Monroe (l. 1758-1831) hostage (the same James Monroe who would later become the fifth president of the United States), and work outwards from the city to emancipate all enslaved people.

Had he not been betrayed, historians speculate, Gabriel's plan could have worked, and it is this aspect of the revolt that caused Whites the greatest fear in that, if something like this could happen once, it might again, and, in fact, it did in 1822 when another literate slave, Denmark Vesey (l. c. 1767-1822), made the same attempt in South Carolina.

Although a slave, Gabriel was hired out as a skilled blacksmith to others and traveled widely in the region, so he was able to personally make contact with co-conspirators in planning the revolt, which was set for 30 August 1800. A heavy rainstorm stalled the uprising, however, giving some of the participants a chance to rethink their position, and two slaves, Pharaoh and Tom, belonging to Prosser's neighbor, Mosby Sheppard, told their master about the revolt. Sheppard then sent a letter to James Monroe, and the alarm was raised.

The planned revolt may have inspired later insurrections, including Denmark Vesey's conspiracy and Nat Turner's Rebellion (1831). Prior to Gabriel's Rebellion, the last major slave uprising was the Stono Rebellion (1739) in what was then the British colony of South Carolina. Gabriel's Rebellion seems to have been more carefully planned than the Stono Rebellion, and, once discovered, it resulted in the same kinds of harsh slave laws in Virginia in 1800 as South Carolina enacted after the Stono Rebellion of 1739.

In 2002, Richmond, Virginia, celebrated Gabriel as a freedom fighter through a resolution commemorating his execution, and, in 2007, the governor of Virginia pardoned Gabriel and the 25 others who were convicted and executed with him.

Background & Gabriel Prosser

The revolt was inspired by the American Revolution (1765-1789), the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), the French Revolution (1789-1799), and the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), and of these, the American Revolution seems to have had the greatest influence, as noted by scholar Douglas R. Egerton:

The very real possibility of liberty, absent before 1775, combined with the incessant white rhetoric of liberty and equality, emboldened the slaves and gave them hope. However much white revolutionaries might try to limit the implications of their words, the significance of 1776 was not lost on black Virginians.

(Gabriel's Rebellion, 7)

Scholar Stephen B. Oates agrees, writing:

The leaders [of the revolt] were chiefly skilled urban slaves who had become highly politicized by the rhetoric of the American and French revolutions – by the enlighted ideal that all men were born equal, that all enjoyed the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness and had a natural right to rebel when those rights were denied. So stated America's cherished Declaration of Independence, yet somehow its noble principles applied only to white people.

(16)

South Carolina had enacted harsher slave laws following the Stono Rebellion of 1739, but Virginia, which also had a large enslaved Black population, had not followed suit. In fact, there was a large free Black community in Virginia c. 1800 due to the efforts of abolitionist evangelicals during the Great Awakening, refugees from the Haitian Revolution, and the work of the Methodists and Quakers, who encouraged abolition. Free men and those slaves who were skilled artisans traveled through Virginia without restrictions, and there was nothing alarming about a slave, like Gabriel, traveling on his own from place to place. Egerton writes:

The conspiracy cannot be divorced from the world of Richmond in the years following the American Revolution. The leading conspirators were slaves, to be sure, but they were slaves who lived and labored in an urban culture that was unusual if not nearly unique in the South. Richmond at the turn of the century had just under six thousand residents. Half of the population was black and about one-fifth of the blacks were free. And, as inhabitants of Virginia, a state with a free black population that was growing rapidly because of manumission and economic change, the border South conspirators dreamed realistic dreams of freedom.

At the heart of the web the conspirators were spinning stood Prosser's Gabriel. Then in his twenty-fourth year, Gabriel was a natural leader, a highly skilled blacksmith who could both "read and write." At six feet odd, Gabriel towered over most men, and he was not afraid to use his strength; in the fall of 1799, he had been convicted of "biting off a considerable part of the left ear" of a white neighbor. As a potential revolutionary, Gabriel had much to lose, for he had recently married. But his emerging plan was based upon careful calculation, and there is absolutely no truth to the popular myth that the short-haired slave was an irrational, messianic figure who wore his locks long in imitation of Samson. As far as the extant evidence indicates, freedom was his only religion.

(Gabriel's Conspiracy, 192)

The White man Gabriel attacked was one Absalom Johnson who caught him, his brother Solomon, and another slave named Jupiter trying to steal one of his hogs. Gabriel defended the other two men and, in the ensuing struggle, bit off Johnson's ear. For assaulting a White man, Gabriel could have been hanged, but because he was an asset of Thomas Prosser, he was given a lesser sentence of a month in jail and a branded thumb, but he did not even serve that time as Prosser paid for his release.

It is unclear how or when Gabriel learned to read and write, but it is possible that his father, also a blacksmith, was literate and had taught his sons. Gabriel's family were all enslaved at Prosser's Brookfield plantation in Henrico County, Virginia, and, when there, Gabriel worked with his brothers Solomon and Martin, but, often, he was away from Brookfield on what today would be known as "freelance work" smithing for other plantations and businesses. Although most of what he earned had to be turned over to Thomas Prosser, he was allowed to keep some for himself, part of which likely went to funding the revolt.

Conspiracy & Betrayal

The web of conspiracy was extensive and involved blacksmiths in different counties beating scythes into swords and creating other weapons. Egerton describes the details of the revolt as Gabriel envisioned it based on the testimony of some rebel slaves given after their arrest:

[Thomas Prosser] would be killed first. The insurgents would then meet at the Brook Bridge, between Prosser's plantation and Richmond. One hundred men would stand at the bridge. Another hundred would go with Gabriel, who was to carry a flag reading "death or Liberty." Wielding the weapons he and Solomon had forged – swords "made of scythes cut in two" – they would storm the capitol, where they hoped Robert Cowley, a free black who served as doorkeeper, would provide them with guns. The third wing of fifty men would set a diversionary fire at Rockett's, a tobacco inspection station in the warehouse district where some of the conspirators labored. Governor Monroe would be taken hostage but not harmed. Enough whites would be killed to force the town's leaders to grant the rebels' demands for freedom.

(Gabriel's Conspiracy, 202)

After Solomon was arrested, he gave a confession to the magistrates M. Selden (or J. Selden) and G. Storrs (recorded on 15 September 1800), explaining the goals of the revolt and how the conspirators armed themselves:

My brother Gabriel was the person who influenced me to join him and others in order that (as he said) we might conquer the white people and possess ourselves of their property. I enquired how we were to effect it. He said by falling upon them (the whites) in the dead of night, at which time they would be unguarded and unsuspicious. I then enquired who was at the head of the plan. He said Jack, alias Jack Bowler. I asked him if Jack Bowler knew anything about carrying on war. He replied he did not. I then enquired who he was going to employ? He said a man from Caroline who was at the siege of Yorktown, and who was to meet him (Gabriel) at the Brook and to proceed on to Richmond, take, and then fortify it.

This man from Caroline was to be commander and manager the first day, and then, after exercising the soldiers, the command was to be resigned to Gabriel – If Richmond was taken without the loss of many men they were to continue there some time, but if they sustained any considerable loss they were to bend their course for Hanover Town or York, they were not decided to which, and continue at that place as long as they found they were able to defend it, but in the event of a defeat or loss at those places they were to endeavor to form a junction with some negroes which, they had understood from Mr. Gregory's overseer, were in rebellion in some quarter of the country.

This information which they had gotten from the overseer, made Gabriel anxious, upon which he applied to me to make scythe-swords, which I did to the number of twelve. Every Sunday he came to Richmond to provide ammunition and to find where the military stores were deposited. Gabriel informed me, in case of success that they intended to subdue the whole of the country where slavery was permitted, but no further.

The first places Gabriel intended to attack in Richmond were, the Capitol, the Magazine, the Penitentiary, the Governor's house and his person. The inhabitants were to be massacred, save those who begged for quarter and agreed to serve as soldiers with them. The reason why the insurrection was to be made at this particular time was, the discharge of the number of soldiers, one or two months ago, which induced Gabriel to believe the plan would be more easily executed.

(James Monroe Highland/Library of Virginia, 1)

The plans were laid with supporters, ready to go on the given date, in the cities of Norfolk, Petersburg, and, especially, Richmond, as well as cities in other counties. The scythes had been turned into swords, the blacksmiths had also made spears and a quantity of musket balls, and it had already been devised how to get hold of muskets. The revolt was ready to be launched – but on 30 August 1800, the skies dropped a pounding rain, turning the streets into running streams and the streams and creeks into overflowing rivers.

The success of the revolt depended on surprise and a swift march on Richmond, and this was now impossible as dirt roads became muddy creeks. Gabriel did not give the signal, no doubt trying to reorganize his plan (though he never said this, nor did he explain much of anything to his captors later), and, once the revolt failed to launch, the two slaves, Pharaoh and Tom, lost their nerve and revealed the plot to their master, Mosby Sheppard, who quickly sent news to Governor Monroe in Richmond.

Arrests, Executions & Aftermath

Monroe mobilized the local and state militia, and companies were posted around the capitol at Richmond and other key points. Patrols scoured city streets and the countryside for anyone, slave or free, who had been part of the conspiracy. Gabriel, with a price on his head, fled to Norfolk and was going to take passage down river when he was recognized by a fellow slave, who turned him in, hoping for the reward; but, as the man was a slave, and therefore property, he received nothing. Gabriel was brought back to Richmond in chains and questioned, but he refused to answer. Others, however, were more vocal, as Egerton notes:

The magistrates and justices, themselves old revolutionaries, found much of the testimony disquieting. Too many of the slaves, reported observer John Randolph, displayed a proud "sense of their [natural] rights [and] a contempt of danger." One insurgent, speaking at his trial, made the political and revolutionary nature of the conspiracy all too evident. "I have nothing more to offer than what General Washington would have had to offer, had he been taken by the British and put to trial," he said defiantly. "I have adventured my life in endeavoring to obtain the liberty of my countrymen and am a willing sacrifice in their cause."

(Gabriel's Conspiracy, 208-209)

Gabriel, Martin, and Solomon Prosser, along with 23 others convicted of conspiracy to incite insurrection, were hanged on 10 October 1800 at the Richmond Gallows. Gabriel was hanged first, and alone, with the others hanged in groups. The revolt had been crushed before it was even launched, and the conspirators had all been executed, but, in the aftermath, the White community was still fearful, as noted by Oates:

Though not a single white had died, the Gabriel conspiracy shook Virginians with volcanic fury, because it seemed incontestable that a [major insurrection] had been boiling right underneath them…John Randolph, who saw the Negroes in prison, warned grimly: "The accused have exhibited a spirit, which, if it becomes general, must deluge the Southern country in blood. They manifested a sense of their rights, and contempt of danger, and a thirst for revenge which portend the most unhappy consequences."

(17)

To ensure no further uprisings, a public guard was established to police the slave population, and calls were made to have free Blacks expelled from the state (though that did not happen). Colonization (sending them anywhere else) of the free Black and slave communities was also considered by the state legislature, but cost and lack of public support led to its rejection. In the end, Virginia followed the same route South Carolina had after the Stono Rebellion and enacted harsher slave laws.

Conclusion

These laws would prove ineffectual and, actually, encouraged greater support for abolition – just as they had in South Carolina after the Stono Rebellion – as Quaker and Methodist clergy, and abolitionists of other faiths, increased their calls for nationwide emancipation of the slaves. White ministers, preaching to Black congregations, sometimes "bravely mixed antislavery sentiments with the gospel" (Gabriel's Rebellion, 8). Egerton writes:

Reduced to its purest form, Christianity carried a subtle political message that was at odds with a class-based society. When "Negro George" preached to the slaves and called them "brother", he implied that all people were equal in the sight of God. The unstated but natural consequence of such a view was the belief that a world that held fast to racial and class distinctions was a world manifestly not in keeping with God's will.

(Gabriel's Rebellion, 8)

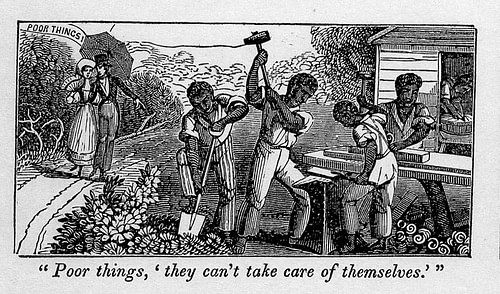

The White populace of Virginia – and elsewhere – ignored this view, however, and, while admitting slavery was a 'peculiar institution', claimed there was nothing they could do to end it and trusted in the enforcement of the slave laws to prevent any further trouble. 31 years later, in Southampton County, Virginia, the slave preacher and mystic Nat Turner would prove just how ineffectual these laws were when he led the deadliest slave revolt in US history.