The galleon (Spanish: galeón, French: galion) was a type of sailing ship used for both cargo carrying and as a warship. Galleons dominated the seas in the second half of the 16th century, and with their lower superstructures, they were much more manoeuvrable and seaworthy than previous ship types like the carrack.

A particular feature of galleons was the impressive number of heavy cannons they could carry. An even bigger version of this class was the Spanish galleon, which compromised speed for greater cargo capacity. The Spanish galleons were used to transport goods from the New World and Asia in the Spanish treasure fleets which sailed to Europe and so they became an irresistible target for pirates and privateers.

Evolution of Mediterranean Ship Design

The galleon was created to meet the new challenges of naval warfare where the strategy of boarding an enemy vessel was replaced by blasting it out of the water using heavy cannons. The galleon, therefore, combined the best design features of three types of ship:

- galley

- caravel

- carrack

Galley

The galley was an evolution of the trireme of ancient Phoenicia and Greece. It was a long, shallow-draught ship, which had a large single sail on a mast positioned two-thirds back from the bow. It was propelled in combat conditions by oarsmen, typically three men to an oar with around 20 oars on each side. The galley had a length-to-beam ratio of 8:1 or more. It was not a vessel that could sail the open sea. The name ‘galleon’ is derived from ‘galley’ as this term had been associated with warships of any kind ever since antiquity.

Caravel

By the 15th century, many European states were keen to expand their horizons and discover new territories for resources and potential colonization. European sailing vessels depended on either teams of rowers or fixed sails or both for their propulsion; the square-rigged barca being the most common. A serious limitation of these vessels was that the sails and rigging required wind from astern. A major improvement in design was required if the High Seas were to become open to exploration where a sailing vessel would need to sail in situations where the wind might be coming from any direction.

The Portuguese prince Henry the Navigator (aka Infante Dom Henrique, 1394-1460) assembled a team of maritime experts at Sagres on the southern tip of Portugal in 1419. They were given the task of creating a new type of ship, and the result of their work, based on a type of Portuguese fishing vessel, was the caravel (caravela in Spanish and Portuguese). The caravel had a shallow draught, was fast, manoeuvrable, and only needed a small crew to sail. The early caravels were small and weighed no more than 80 tons, but later versions did increase to 100-150 tons and even over 300 tons in the round caravel or caravela redonda class.

A caravel had a stern rudder, two or three masts, and a distinctive raised forecastle and sterncastle. A caravel had a typical length-to-beam ratio of 3.5:1. A crucial part of the design was the use of square and lateen or triangular sails. The lateen sail’s name derives from ‘Latin’ even if it was inspired by the sails of Arab sailing vessels, particularly the dhow with its single lateen sail. Flexible lateen sails permitted a vessel to sail within five points off the wind and even to tack (move in a forward zigzag) against a headwind. The Matthew of John Cabot (c. 1450 - c. 1498) and the Niña and Pinta of Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) were caravel ships.

Carrack

Over time, caravels became bigger, the largest type being a four-masted caravel with a bowsprit with spritsail designed for use as a warship. Then, as the maritime powers built colonial empires, they required ships to carry large volumes of goods. The next move forward in ship design was, therefore, the carrack (nao in Spanish, nau in Portuguese, and nef in French). This type of ship could carry many hundreds more tons of cargo than the caravel. Carracks had a frame-built hull with four decks. They had a 2:1 ratio of length-to-beam, which gave them greater stability in heavy seas, although this reduced manoeuvrability. Castle-like superstructures for accommodation were built high at the bow and stern. Like the largest caravels, the carrack had three or four masts and carried a mix of square and lateen sails.

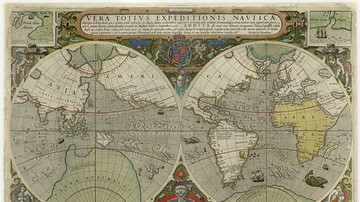

Famous carracks include the Santa Maria of Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) and the Victoria, which completed the first circumnavigation of the globe in 1522 as part of the expedition led by Ferdinand Magellan (c. 1480-1521). In the second half of the 16th century, the dominance of the carrack was challenged by the appearance of a new vessel: the galleon.

The Galleon Design

The galleon was larger and more seaworthy than its predecessors in European navies. It was used as both a merchant vessel and the warship of choice for European maritime powers. The galleon combined the best design features of the caravel and carrack but had much lower forecastles, was faster, more manoeuvrable, and could carry many more heavy cannons. The distinctive beak-like prow of the galleon was inspired by the more pronounced version on a galley.

The galleon usually had a length-to-beam ratio of 3:1. Galleons had a smooth carvel hull, often made of Indian teak, Brazilian hardwood, or Asian hardwoods like molave and lanang. The exterior of the hull was covered with a thick black tar mixture above the waterline to prevent rot. Below the waterline, hot pitch was used to coat the planks to increase the water resistance of the wood. Then a mixture of pitch and tallow (animal fat) was smeared all over the hull to deter marine animals and especially shipworms.

The reduced superstructures of the galleon were used for accommodation for officers and marines while ordinary crew members - who could number over 300 - slept in cramped conditions below deck in a period when the hammock had yet to fully catch on.

Counterbalancing the superstructures were an array of heavy cannons, arranged below decks on both sides of the ship. When required for battle, the muzzles of the cannons were rolled out to point through gun ports, wooden windows in the deck which could be closed when not in use. These gun ports ran down both sides of the ship, sometimes with multiple levels. In addition - and unlike the carrack - a galleon could fire cannons from both the bow and stern. A large Spanish galleon could carry at least 40 heavy cannons below decks. Additional smaller cannons were mounted on swivel posts at various points on the top deck; these typically had a calibre of 90 mm (3.5 inches). A major disadvantage of galleon firepower was that the cannons were so heavy they could not be turned very much, if at all, towards a fast-moving opponent, the ship itself had to turn to keep an enemy vessel in range.

As ship captains tried to carry more and more cannons, so galleons became bigger, culminating in the Spanish galleon class. These ships also had thicker hulls to better withstand cannon shots. Cannons were not only needed in naval battles but to fight off the privateers and pirates who lay in wait for ships carrying the treasures of the empire across the globe. Indeed, over time, the bulky Spanish galleon with its markedly larger sterncastle was often reduced to use as a cargo carrier only because the compromise in speed and manoeuvrability their greater size necessitated made them less useful against more agile smaller galleons in sea battles. These cargo ships could, though, still fire tremendous broadsides.

Spanish galleons famously brought to Europe the gold of the Americas and the silver of East Asia via the Spanish Philippines - the Manila galleons - while the Portuguese version helped maintain such colonies as the Estado da India and Portuguese Brazil. This made them irresistible targets not only for the pirates of the Caribbean but pirates anywhere from the Azores to the Straits of Malacca.

Race-built Galleons

A new direction in ship design came from French corsairs eager to run rings around galleon treasure ships. They reduced the size of the galleon and removed one deck so that the ship was described as razde or shaved. This name was lost in translation in English, and became ‘race-built’. In addition, the hull above the waterline now tapered in towards the top deck, giving the ship a lower centre of gravity. These design tweaks made for a much faster and more manoeuvrable vessel. Corsairs could then attack larger galleons and avoid their cannon fire.

The English also saw the value of a sleeker version of the galleon, beginning with works supervised by John Hawkins (1532-1595) in the 1570s. Hawkins became Treasurer of the Royal Navy, and he oversaw the construction of such famous galleons as Ark Royal and Revenge (see below). Other innovations included the introduction of four-track carriages to wheel cannons in and out of the gun ports. The carriage speeded up reloading times and allowed the cannons to fire heavier shots. It also resulted in much less stress being put on the ship’s hull because the cannon’s recoil was absorbed by the carriage. Galleons were given greater ventilation for the greater comfort and safety of seamen, and flatter sails were used, which made them easier to handle and which gave the ship greater speed.

The English navy reaped the rewards of having faster ships with greater firepower in 1588 when they met and defeated the Spanish Armada of King Philip II of Spain (r. 1556-1598). The Armada was massive and boasted 132 ships in all. It was designed to achieve Philip’s great ‘Enterprise of England’: to defeat the Royal Navy and permit a land invasion of England. The Spanish galleons sailed up the English Channel in their disciplined line-abreast formation, creating a giant crescent across the waves. The weather did much to defeat the Spanish, but the speed, manoeuvrability, and superior cannons of the 20 galleons in the Royal Navy fleet were by no means an insignificant factor in victory. The Spanish did respond to the evolution in ship design with their own slimmed-down galleon, the galizabra, which they used to more safely transport the riches of their empire back to Spain. This was now the trend in 17th-century ship design as the large and unwieldy galleon was replaced by sleeker vessels like the brigantine, barque, and frigate.

Famous Galleons

Golden Hind

The most famous English galleon is the Golden Hind of Sir Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596). This was the race-built galleon in which Drake circumnavigated the globe between 1577 and 1580, only the second such voyage after Magellan’s expedition. The Golden Hind was not a large galleon at only 140-150 tons, around 30.5 metres (100 ft) in length, and with a 5.5-metre (18 ft) beam. The draught when fully loaded was almost 4 metres (13 ft). The ship had a crew of 90 men, a total sail area of 385 square metres (4,150 sq. ft), and sported seven cannons on each side, two more on the poop deck, and a number of smaller cannons if required. An experienced Portuguese pilot, Nuño da Silva described the Golden Hind as:

…very stout and very strong, with double sheathings…She is a French [style] ship well-fitted with good masts, tackle and good sails, and is a good sailor, answering the helm well. She is neither new, nor is her bottom covered with lead…She is staunch when sailing with the wind astern if it is not very strong, but in a sea which makes her labour she makes no little water.

(Williams, 119)

The ship certainly was "stout and very strong" as it made the voyage around Cape Horn, up the western coast of South America, made a brief search for the North-West Passage in North American waters, sailed across the Pacific Ocean, across the Indian Ocean, and around the Cape of Good Hope to home.

During the epic 33-month voyage, Drake captured another famous galleon, the Cacafuego (Nuestra Señora de la Concepción) in March 1579 off the coast of Peru. The capture of the galleon’s massive cargo of Inca gold and silver was one of the richest prizes taken by the Elizabethan privateers. Drake had also loaded up his ship with spices in the Spice Islands and as a reward for his contribution to the royal coffers, Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603) knighted the mariner on-board the Golden Hind in April 1581. Now with a right to a coat of arms, Drake chose a galleon sailing above a globe for its design.

Revenge

The Revenge was another famous English galleon, used by Drake as his flagship in the battle with the Spanish Armada. The Revenge gained even greater fame when, in 1591 in the Azores, it was captained by Sir Richard Grenville (1542-1591). A small English fleet lay in wait for Spanish treasure ships but was surprised by a much larger fleet, perhaps 56 ships. As his fellow captains raised anchor and fled, Grenville was left to face the enemy alone. The Revenge put up a heroic defence for over 15 hours, sinking two enemy ships and damaging many others, but eventually, it succumbed to the inevitable, and Grenville died of his wounds. The capture of the Revenge became the stuff of legend and was commemorated in songs, art, and literature for centuries thereafter.

Vasa

The only original galleon which survives is the 17th-century Vasa. A Swedish galleon, the 1,200-ton Vasa boasted two gun decks, which sported a total of 64 cannons. The ship was made especially wide to accommodate the tremendous weight of iron, and there was a magnificent aft castle enriched with decorative carvings extolling the virtues of King Adolphus of Sweden (r. 1611-1632). Unfortunately, and to everyone’s horror watching from the shore, Vasa sank to the bottom of Stockholm’s harbour minutes into its maiden voyage in August 1628. The fate of the ship is the most infamous example of how a top-heavy galleon was prone to sudden changes in wind direction. In 1961, the ship was retrieved, faithfully restored, and it now has its own dedicated museum in Stockholm. The magnificent but ill-fated Vasa is one of Sweden’s top tourist attractions.

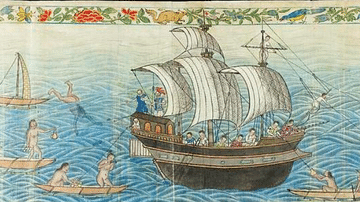

Representations of Galleons

Perhaps the most famous book, packed full of depictions of caravels, carracks, and galleons, and other vessels of the period sorted by expedition fleets, is the mid-16th century Livro das Armadas now in the Academy of Sciences in Lisbon. Another interesting catalogue of ships is the 1616 Livro das Traças de Carpinteria, which is, in effect, a construction manual and so shows illustrations of specific parts of ships in detail. A celebrated 1626 engraving by Friedrich van Hulsen shows the Golden Hind and the Cacafuego in close battle. The engraving is now in the Library of Congress, Washington D.C. Galleons and sea battles became a favourite subject of many oil painters, too, particularly the Flemish masters. Finally, full-size replicas capable of sailing the seas have been made of several galleon ships, notably the Golden Hind on the south bank of the River Thames, London. Another fine example of a scale replica is the 17th-century Spanish galleon El Galeón (Galeón Andalucía), moored in Quebec City, Canada.