Genghis Khan (aka Chinggis Khan) was the founder of the Mongol Empire which he ruled from 1206 until his death in 1227. Born Temujin, he acquired the title of Genghis Khan, likely meaning 'universal ruler’, after unifying the Mongol tribes. Utterly ruthless with his enemies, countless innocents were slaughtered in his campaigns of terror - millions according to medieval chroniclers.

Genghis Khan attacked the Xi Xia and Jin states and then Song China. In the other direction, his fast-moving armies invaded Persia, Afghanistan, and even Russia. Genghis Khan had a fearsome reputation but he was an able administrator who introduced writing to the Mongols, created their first law code, promoted trade and granted religious freedom by permitting all religions to be freely practised anywhere in the Mongol world. In this way, Genghis Khan built the foundations of an empire which would, under his successors, ultimately control one-fifth of the globe.

Early Life

Genghis Khan's life is told in the (sometimes fantastical) Secret History of the Mongols parts of which likely date to the first half of the 13th century as well as later Chinese and Arab sources. He was born to aristocratic parents and was given the birth name of Temujin (Temuchin), named after a Tartar (Tatar) captive. The date of birth is not known for certain with some scholars choosing 1162 and others 1167. Legend has it that the infant was born clutching a clot of blood in his right hand, an ominous omen of things to come. Temujin's mother was called Hoelun and his father, Yisugei, who was a tribal leader, and he arranged for his son to marry Borte (aka Bortei), the daughter of another influential Mongol leader, Dei-secen, but before this plan could come to fruition, Temujin's father was poisoned by a rival. Temujin was still only nine or twelve years old at the time and so he could not maintain the loyalty of his father's followers. As a consequence, he and his mother were abandoned on the Asian steppe, left to die. However, the outcast family managed to forage and live off the land as best they could.

Things then got even worse when the young Temujin was captured by a rival clan leader, perhaps following an incident where Temujin may have killed one of his older half-brothers, Bekter, who likely represented a rival branch of the family that had taken on the legacy of Yisugei. Fortunately, Temujin was able to escape during the night and, gathering around him the few still-loyal followers of his father, he joined up with Toghril, chief of the Kerait, a tribe that his father had once helped. Temujin then married his betrothed from several years earlier, Borte.

Before long the leadership and martial talents of Temujin brought him victories over local rivals and his army grew in size. The conflicts were bitter with one tribal leader infamously boiling his captives in 70 large cauldrons. Temujin proved unstoppable, though, and he managed to unify most of the different nomadic tribes which roamed the grasslands of central Asia, each one composed of different but related clans, by creating a web of alliances between them. Temujin made himself the dominant leader through a mix of diplomacy, generosity, and his own ruthless use of force and punishments. Defeated tribes were sometimes compelled to join his army or killed to a man. Courageous himself in battle, Temujin would often reward bravery shown by the defeated, famously making a man called Jebe one of his generals because he had withstood a cavalry charge and fired an arrow that felled Temujin's own horse.

The Great Khan

As his army swelled to ever greater proportions, Temujin defeated, over a period of ten years or so, such rivals as the Tartars, Kereyids, Naimans, and Merkids until a Mongol confederation met at a great conference or kurultai at the Kerulen river in 1206 and formally declared Temujin their leader. He was given the title of Genghis Khan which likely means 'universal' leader (the spelling in Mongol is Chinggis but 'Genghis' remains more familiar today and derives from medieval Arab scholars not having a ch in their language).

The aim now was to combine this power base with the traditional Mongol skills of horsemanship and archery, and, not only overcome tradition rival neighbouring states but build an empire which then could conquer the richest state in Asia: China. Genghis may not have started out with this plan but that is exactly what happened.

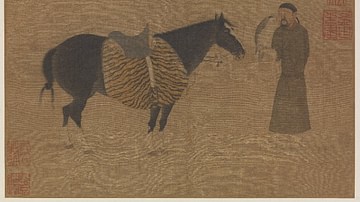

Despite his now elevated position, Genghis would remain close to his roots and continue to live in a large portable wool-felt tent or yurt. Indeed, until the Mongol Empire established itself these nomadic people had not formed villages or towns but moved regularly between pastures as the seasons dictated. The Great Khan did not always look backwards, though, and he insisted that the hitherto only spoken Mongol language was now made into a written one using the script of the Uighur Turks. Consequently, a law code, the Yasa, could now be drawn up with, amongst many other provisions, punishments for specific crimes laid out. Another innovation was the development of a postal system where horse-riding couriers could quickly carry messages across long distances and who were provided with regular stations for food, rest, and a change of horse. The network would prove extremely useful during campaigns when military intelligence needed to be passed on quickly.

Genghis also made his army more secure by avoiding the Mongol tradition of forming divisions based on tribes which then might split due to age-old rivalries. To better secure his own position, the Great Khan formed and then expanded his elite bodyguard, the kesikten, from 800 to 10,000 men. Traditionally, their loyalty was ensured by the corps' diverse composition and the fact its members were drawn from the sons and brothers of his senior commanders. Later, its members swore absolute loyalty to the Khan in return for special favours when it came to war booty. In addition, many of its members also acquired important administrative functions in conquered territories.

Mongol Warfare

The Mongols were now unified and their army had several advantages over those of their larger and more powerful neighbours. They were expert archers using their far-shooting composite bows and extremely tough soldiers, capable of riding for days on end with minimal food and water. Their stocky but nimble horses were a weapon in themselves and capable of surviving harsh temperatures. The Mongols had both light and heavy cavalry, and each rider typically had up to 16 spare horses giving them a very long range of manoeuvre. On top of that, the Mongols never turned down an opportunity to employ enemy tactics and technology themselves. They not only brought ferocious mobility to Asian warfare but they were, thanks to their flexibility, quickly adept at other types of battle, too, like siege warfare and the use of gunpowder missiles and catapults (first Chinese ones and then those from Afghanistan were adopted when they realised they were superior). Adopting the skills and innovations of others became a forte in general as the Khan's ministers and commanders came from some 20 different nations.

Another advantage was that Genghis Khan knew how to exploit internal divisions in the enemy and stir up old rivalries that could weaken enemy alliances, information often acquired by spies and merchants. Finally, motivation was high because Mongol warfare was designed for one purpose only: to gain booty. Further, victorious commanders could expect to receive large swathes of land to govern as they pleased while the Great Khan himself received tribute from those rulers permitted to stay in power as Mongol vassals. In short, once mobilised, the Mongol hordes were going to prove very difficult indeed to stop.

The Mongol Empire

The Jin State

Genghis attacked the Jin state (aka Jurchen Jin Dynasty, 1115-1234) and the plain of the Yellow River in 1205, 1209, and 1211, the latter invasion consisting of two Mongol armies of 50,000 men each. The Jurchen controlled most of northern China and were able to field 300,000 infantry and 150,000 cavalry but the Mongol high-speed tactics proved that numbers were not everything. Genghis would savagely sack a city and then retreat so that the Jin could retake it but then have to deal with the chaos. The tactic was even repeated several times on the same city. Another strategy was to capture one city, devastate it, murder every citizen, and then warn neighbouring cities the same fate would befall them if they did not immediately surrender. There were also acts of terror such as using captives as human shields. One Jin official, Yuan Haowen (1190-1257) wrote the following poem to describe the devastation of the Mongol invasion:

White bones scattered

like tangled hemp,

how soon before mulberry and catalpa

turn to dragon-sands?

I only know north of the river

there is no life:

crumbled houses, scattered chimney smoke

from a few homes.

(Ebrey, 237)

To add to the Jin's woes, they were beset with internal problems such as chronic corruption emptying the state coffers, natural disasters, and assassinations of top officials, including Emperor Feidi in 1213. The Jin rulers were compelled to retreat south, sign a peace deal and pay tribute to the Great Khan in 1214, although they were probably glad to, faced with the stark alternative. It was a respite but worse was to come as the Mongols re-attacked the Jin in 1215 after they moved their capital south, and Genghis took this as a repudiation of their vassal status.

Xi Xia & Song China

Also in 1215, the Great Khan attacked the Tangut state of Xi Xia (aka Hsi-Hsia, 1038-1227) in northern China, repeating his raids there of 1209. Rather short-sightedly, the fourth player in this game of empires, the Chinese Song Dynasty (aka Sung, 960 - 1279), instead of allying with the Jin to create a useful buffer zone between themselves and the Mongols, allied with the Khan. Admittedly, the Jin and Song had been attacking each other since the previous century and the Song even paid tribute to keep the Jin raids to a minimum.

The Mongols continued their attacks on China over the next decade, with around 90 cites being destroyed in 1212-1213 alone. Many disgruntled or captured Chinese and Khitan (steppe nomads who had once ruled supreme in northern China and Manchuria) soldiers were absorbed into the Mongol army along the way. The Song launched a counterattack into Mongol territory in 1215 which ultimately failed and the Chinese general P'eng I-pin was captured, a fate which befell one of his successors in 1217. Also in 1215, Beijing was captured and the city burned for a month. Even Korea did not escape the Khan's attentions with an invasion force chasing down fleeing Khitans in 1216 and a Korean army then supporting the Mongols in battles against the Khitans in 1219.

After a period of relative stability, the Mongols would once more go on the march, attacking Korea again in 1232 and 1235, and China in 1234, finally bringing about the collapse of the Jin state. It was now clear they would not be satisfied until they had conquered the whole of East Asia. Song China was now fully exposed from the north and weaker than ever, wracked as it was by internal political factions and hamstrung by an overly conservative foreign policy which meant that it was only a matter of time before the Mongols brought about its collapse, too.

Western Asia

Genghis Khan was far from satisfied with the imminent fall of China, though, and turned his army to the southwest and invaded what is today Turkistan, Uzbekistan, and Iran between 1218 and 1220. The target was the Khwarazm Empire. Genghis had sent a diplomatic mission requesting the Shah of Khwarazm submit to his overlordship, but the Shah had the ambassadors executed. Genghis responded by fielding an army of some 100,000 men which swept through Persia and forced the Shah to flee to an island in the Caspian Sea. Bukhara and Samarkand were captured amongst other cities and the Great Khan was utterly ruthless and unforgiving, destroying countless cities, murdering innocents and even wrecking the region's excellent irrigation system. Not for nothing did he become known as 'Evil One' or the 'Accursed One.' In 1221 the Mongols swept into northern Afghanistan, in 1222 a combined army of Rus principalities and Kipchaks was defeated at Kalka, and then the Caspian sea was entirely encircled as the army returned to Mongolia.

The Mongol's fearsome reputation as the military equivalent of a great plague was now firmly established. There was, though, another side to Genghis Kahn's conquests. He knew that to keep hold of his territorial gains and ensure they continued to produce riches he could regularly cream off, there had to be in place some system of stable government. Accordingly, rulers were often permitted to keep power, there was religious tolerance for all the different faiths within the empire, international trade was encouraged and travelling merchants were given protection.

The campaigns in Western Asia and the edge of Europe brought Genghis Khan and the Mongols to the attention of a different set of historians than the Chinese, notably the Persian Minhaj al-Siraj Juzjani (b. 1193), who made the following description of the Great Khan, by then already a legendary figure:

A man of a tall stature, of vigorous build, robust in body, the hair on his face scanty and turned white, with cat's eyes, possessed of great energy, discernment, genius and understanding, awe-inspiring, a butcher, just, resolute, an overthrower of enemies, intrepid, sanguinary and cruel' (Tabakat-i Nasiri, c. 1260, quoted in Saunders, 63)

Death & Legacy

Genghis Khan died on 18 August 1227 of an unknown illness, perhaps initially caused by falling from his horse while hunting a few months earlier. At the time, he was back in northwest China besieging the Xia state's capital, Zhongxing, and the news of the great leader's death was kept from the Mongol army until the city had capitulated and its inhabitants been slaughtered. His body was then transported back to Mongolia for burial but the location of his tomb was kept a secret, a decision that has caused much speculation ever since. Medieval sources mention the tomb was in the vicinity of the sacred mountain Burkan Kuldun, and that his son Ogedei sacrificed 40 slave girls and 40 horses to accompany his father into the next life.

Genghis knew that his successors would dispute control of the Mongol Empire after his death and so he had already made provisions. The empire was to be divided amongst his sons Jochi, Chagatai (Chaghadai), Tolui (Tului), and Ogedei (Ogodei), with each ruling a khanate (although Jochi would predecease his father in 1227) and Ogedei, the third son, becoming the new Great Khan in 1229, a position he would maintain until his death in 1241. The next big step forward came during the reign of Kublai Khan (r. 1260-1294), the grandson of Genghis who conquered most of what remained of China from 1275 and so caused the collapse of the Song Dynasty in 1279. Kublai proclaimed himself emperor of the new Yuan Dynasty in China. Over the next two decades, China would become entirely dominated by the Mongols. The Mongol Empire would then go on to more campaigns, including in the Middle East, Korea, and Japan with varying success but ultimately creating one of the largest empires ever seen.

Genghis Khan has left a much longer shadow than his empire, though, as he has come to be seen as nothing less than a god-like figure in the region and a father of the Mongolian people. Worshipped in the medieval period, his veneration has been revived in modern times, and today he continues to be honoured with special ceremonies in the modern Mongolian capital of Ulaanbaatar.