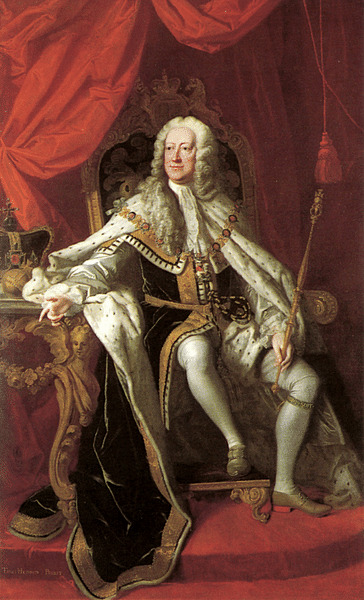

George II of Great Britain (r. 1727-1760) was the second of the Hanoverian monarchs, and like his father George I of Great Britain (r. 1714-1727), he faced a Jacobite rebellion to restore the Stuart line. Wars in Europe and beyond drained resources but ultimately led to Britain holding many key colonies in the now truly global game of empires.

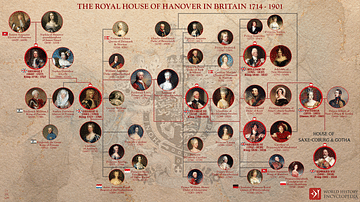

The House of Hanover

King George I became the first Hanoverian ruler in Britain in 1714 thanks to Queen Anne of Great Britain (r. 1702-1714) having no children. George was Elector of Hanover, a small principality in Germany, and the queen's nearest Protestant relative. He did have a remote connection to the royal Stuart line as he was a descendant of Elizabeth Stuart (d. 1662), daughter of James I of England (r. 1603-1625). George spoke only rudimentary English, and he often spent long stays in Germany, which did not endear him to his new subjects. He did not get on well with his son and only heir either.

Family

George August, future George II, was born on 10 November 1683 at Herrenhausen in Hanover. He was, therefore, the last British monarch to be born outside Britain. He was the eldest child of George I and Sophia Dorothea of Celle (l. 1666-1726). His parents' marriage had been one of political convenience, and there was little love between the two. When Sophia was discovered to have carried on an affair with a Swedish count in 1694, George arranged for a divorce. Sophia was permanently banished to Ahlden House in Celle, and she was not permitted to see her son or daughter Sophia Dorothea, who went on to become queen in Prussia through marriage. From the age of eleven, then, Prince George never saw his mother again, and he greatly resented his father for this.

On 2 September 1705, Prince George married Caroline of Ansbach (1683-1737), the daughter of Johann Friedrich, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach. Caroline was praised in England for having refused a marriage to a future Holy Roman Emperor because it would have been necessary for her to convert to Catholicism. The couple had seven surviving children. George's eldest son and heir was Frederick Louis (b. 1707), who died nine years before his father in 1751. His second son Prince George William was born in 1717, but he died the next year. The third son was William Augustus (b. 1721), who became better known as the Duke of Cumberland. The eldest daughter Anne (b. 1709) became Princess of Orange through marriage, while Louise (b. 1724) became the Queen of Denmark and Norway, also through marriage. The three other daughters were Amelia (b. 1711), Caroline (b. 1713), and Mary (b. 1723).

Succession

When his father became king of Great Britain in 1714, Prince George followed him to England. George was made Prince of Wales, as was the custom. Unlike his father, the prince spoke good English, albeit with a heavy German accent, and he made sure to (at least in public) make positive comments about his adopted home. He had already endeared himself further to his future subjects through his military exploits, fighting with the Duke of Marlborough at the Battle of Oudenarde in 1708 during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-15). Princess Caroline, too, became popular thanks to her good looks, tact, and support of public institutions like Queen's College, Oxford. Caroline very much filled the gap left by the forced absence of Queen Sophia and the king during his regular sojourns in Hanover. Later, as queen, Caroline had a great influence on her husband, often persuading him of policies secretly promoted to her by the Whig prime minister Sir Robert Walpole (1676-1745). As Walpole once stated: "She can make him propose the thing which one week earlier he had rejected as mine" (Starkey, 426).

King George I and his heir fell out publicly and spectacularly in 1717, the crisis coming at the christening of Prince George's son. The king banished George from St. James' Palace and even took custody of his grandchildren, permitting only one weekly visit with their parents. Prince George then set up a rival court centred around Leicester House. The prince's court attracted conspirators, discredited Tories, and the out of favour Walpole, amongst others. Royal relations were restored somewhat in April 1720, but the bond between king and heir was never quite the same again. The king suffered poor health in his later years, and he died on 11 June 1727. Prince George consequently became George II of Great Britain, and he also took on his father's title of Elector of Hanover.

George I had been a fan of the composer George Frideric Handel (1685-1759), and George II was too. At the coronation in Westminster Abbey on 11 October 1727, four new pieces by Handel were played, including the rousing Zadok the Priest, which has been played at every British coronation since.

Character & Fallout with His Heir

George II was a complex and difficult character, as here summarised by J. Black:

George's eccentricities obscured his virtues. His judgement was basically sound, but bad temper and bluster made it seem erratic. Though he aimed at royal dignity, it was marred by pomposity and self-satisfaction; his courage was undoubted, but he talked about it too often. His ungraciousness was proverbial, but he was lacking in malice, and honest to a fault.

(Cannon, 320)

Just as he had not gone on with his own father, the quick-tempered king had a poor relationship with his heir, Frederick Louis. William Augustus became his father's favourite instead. The debt-ridden Frederick, just as his father had done when he was Prince of Wales, set up his own rival court at Leicester House. Even Frederick's own mother could not abide him and described him on her deathbed as "that monster" (Phillips, 184).

Queen Caroline died on 20 November 1737 at the age of 54. The king had had plenty of mistresses, but he had always maintained a good relationship with his wife and was devoted to her in a family sense. In 1740, one of the king's German mistresses, Amelia Sophia Walmoden, was made the countess of Yarmouth. Two notable English mistresses were Henrietta Howard, Countess of Suffolk, and Mary Scott, Countess of Deloraine.

The Jacobite Rebellion

The Jacobites were those who supported the claim to the British throne through exiled James II's son James Francis Edward Stuart (1688-1766), also known as the Old Pretender (from the French word pretendant, meaning 'claimant'). The Old Pretender, who also represented a return to a Catholic monarchy, failed dismally to seize the throne in the winter of 1715-16, in 1719, and in 1722. His much more charismatic son then took up the cause as the Young Pretender, although he was actually championing his still-alive father's cause. Charles Edward Stuart, also known as 'Bonnie' Prince Charlie (1720-1788), led a major Jacobite rebellion in 1745.

The 'Bonnie' prince landed in Scotland in July 1745 with an entourage of no more than a dozen men. He moved out from the Hebrides and managed to gain the support of the MacDonald and Cameron clans. From its initial headquarters at Loch Shiel, the growing army marched to Perth and then the capital, Edinburgh. The initial loyalist response was inadequate, and 'Bonnie' Prince Charlie won the Battle of Pestonpans near Edinburgh on 21 September. To bolster English hopes during the rebellion, a popular song did the rounds with lyrics by an unknown writer. This song became the national anthem in 1819 and remains so today (albeit slightly modified), called after the third line of its opening verse "God Save the King".

Charles Stuart then led his army into England in November with no less a target than London in his sights. The army reached Derby by December, but, crucially, no support was forthcoming from England. The Stuart army only numbered 4-5,000 men, which led to the sensible decision to withdraw back to Scotland. It had been 57 years now since James II had fled England, and most people could not even remember the days of the Stuarts. The government's second response to the rebellion was much more effective. An English army of 9,000 men led by the Duke of Cumberland marched to Scotland and crushed the smaller and ill-equipped Jacobite army at the Battle of Culloden on 16 April 1746. The Young Pretender escaped the battle and the massacre of wounded and prisoners afterwards that earned the victorious duke the title of 'Butcher' Cumberland. The pretender survived several months as a fugitive in the Highlands until he left for France dressed as a maid. A secret trip to London in 1750 did not further his now hopeless cause, and Charles Edward Stuart lived the rest of his days in exile in Italy; he died in 1788 and left no children.

George II was determined to punish those Scottish clans that had supported his rival for the throne. Executions, massacres, and looting brought misery to many Scottish communities. A wave of repressive legislation attempted to eradicate Scottish nationalism. Highland tartan and clothing were prohibited, as was the carrying of weapons. English troops were garrisoned around Scotland, but new regiments were created of Scots, too, such as the famous Black Watch.

Foreign Wars

George's reign involved wars across the globe as the European powers jostled to grow their empires. A conflict broke out between Britain and Spain in 1726 when the latter tried and failed to retake Gibraltar. A peace treaty was signed in 1729 which confirmed Gibraltar as a British possession and permitted British trade with the colonies in Spanish America. In 1732, the king granted a royal charter to a new colony in North America, which was founded the year after and named after him Georgia.

In Europe, the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) pitched Britain and Austria against Spain, France and Prussia (along with several more states on each side). The conflict, initially fought in Central Europe, was not popular since many considered it an exercise in expanding the interests of Hanover at the cost of British lives. As it happened, in Britain's constitutional monarchy, it was politicians like Walpole and William Pitt the Elder (1708-1778) who were calling the shots. George himself wryly noted that, unlike in his beloved Hanover where he had absolute power, in Britain: "Ministers are the kings in this country" (Miller, 344). King George at least involved himself personally in the war, leading an army to victory at the Battle of Dettingen in Bavaria in 1743 alongside the Duke of Cumberland. This battle was not of any great importance, but it was significant as the last time a British monarch led an army in the field.

The War of the Austrian Succession spilled over into other continents, essentially wherever the opposing states already had interests and colonies. There was the War of Jenkin's Ear (1739-1748) fought in northern South America and the Caribbean against the Spanish; a costly and ineffectual war for all parties. In North America, there was another indecisive conflict, known in Britain as King George's War (1744–1748), which was fought against France.

The Seven Years' War (1756-1763) outlasted George's reign and was another cross-European, intercontinental conflict, one which saw Britain and Prussia against Spain and France (and several other states). There were notable British losses early on, but a highlight of all of the many splinter conflicts and military escapades was the British capture of Quebec in 1759 and Montreal and the rest of Canada in 1760. Britain and Prussia finally won the war with the former, in particular, benefiting from a reshuffle of colonies to gain dominance in the eastern side of North America, the Caribbean, and India. The Indian subcontinent, where the East India Company began a series of lucrative conquests starting with the Battle of Plassey in 1757, was viewed as the corner of the empire with the greatest potential. In short, then, Britain was now set up to build a massive global empire through the next century.

The Arts

The Georgian style in architecture continued to spread with each new building. This style, where symmetry and proportion are emphasised, lasted right through the reign of the House of Hanover. The rather austere style was a sort of reaction against the highly decorative Baroque style seen in Continental Europe, and it eventually developed into the Neoclassical style where elements of the Doric and Ionic orders of ancient Greek and Roman architecture were used with a new toned-down approach to create uniform buildings, squares, and whole avenues of street houses.

The Georgian style (or perhaps more accurately, Georgian styles) in architecture crossed over into the visual arts, notably in clean-looking ceramics (e.g. Wedgwood), curvaceous furniture (e.g. Chippendale), and rich interior design (especially decorative wallpaper). Landscape gardening was another area of development in the Georgian period. Queen Caroline was particularly interested in horticulture and supported Kensington Gardens. The flourishing of the arts in Georgian Britain attracted such painters as Canaletto (1697-1768), who spent a decade painting in London from 1746 to 1756.

George II was known for his dislike of learning and books, but he did oversee some major cultural innovations. In June 1753, the king gave financial support for the foundation of the British Museum. The king also helped the museum improve its collection by donating the 'Old Royal Library' a collection of over 10,000 books. In 1749, Henry Fielding's (1707-1754) celebrated novel Tom Jones was published, and in 1755, Dr Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) released his mammoth Dictionary of the English Language.

Death & Successor

The king suffered ill health in his later years; he lost his sight in one eye and was deaf, too. George II died of a heart attack on 25 October 1760 in Kensington Palace. He was 76, significantly older than many other males managed to reach in the House of Hanover. He had presided over a difficult reign at home and abroad, but Britain ended stronger than when he had first sat on the throne. The king was buried in Westminster Abbey alongside Queen Caroline, thus achieving his third major 'last' achievement, in this case, the last British monarch to be buried in the abbey.

As George II's eldest son Frederick had died in 1751 after being hit in the chest by a cricket ball (or a tennis ball or struck down by just plain pneumonia), the crown passed to Frederick's eldest son George William Frederick (b. 1738) who became George III of Great Britain and Ireland. George ruled for six decades, longer than any other king in British history, but his term was marred by the loss of the American colonies and his own descent into madness.

The Hanoverians continued to endure as Britain built its empire thanks to its politicians and armies rather than its sovereigns. The direct British connection with Hanover itself ended when Queen Victoria took the throne in 1837 since a woman was not permitted to rule the German kingdom.