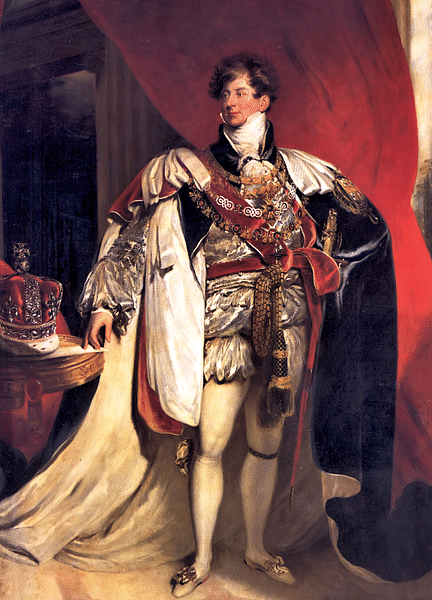

George IV of Great Britain (r. 1820-1830) was the fourth of the Hanoverian monarchs. He first reigned as Prince Regent from 1811 for his mad father George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820). George IV was an unpopular monarch for his many love affairs and overspending, but he was a great patron of the arts and architecture. He was succeeded by his younger brother William IV of Great Britain (r. 1830-1837).

The House of Hanover

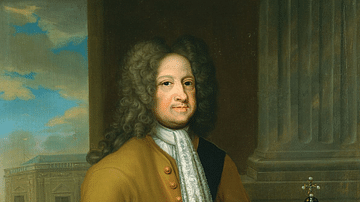

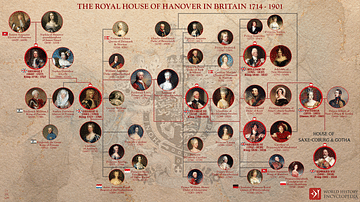

The royal house of Hanover had taken over the British throne in 1714 following the death of Queen Anne of Great Britain (r. 1702-1714), who had no children. The Hanoverians were also electors of Hanover, a small principality in Germany, and so both George I of Great Britain (r. 1714-1727) and George II of Great Britain (r. 1727-1760) were very much Germans ruling in Britain. George III was the first Hanoverian to be born in Britain and to speak English as his first language, and he was, consequently, more popular with his subjects.

Character & Relationships

George Augustus Frederick was born on 12 August 1762 at St. James' Palace. His father was George III, and his mother was Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1744-1818). He had many siblings, amongst them his younger brother William, born in 1765. The heir, like most Hanoverians before him, seemed unable to get on with his father. George was the typical playboy prince, despite his father's care in trying to raise an honest and reliable future king. It may have been the restrictive and austere court that the king ran which pushed the heir to his dalliances and folly. Prince George in his youth is described as follows by one historian:

He was lazy, irresponsible, a fashionable man about town, a superb mimic, a charmer and a spendthrift who lavished money far beyond his means on clothes, horses, buildings, smart parties and a cavalcade of women.

(Cavendish, 384)

The prince's love affairs became a great embarrassment to his father. Aged 16, the prince wrote compromising letters to an actress, Mary 'Perdita' Robinson, and when the affair ended she threatened to publish them. The king was obliged to buy the letters back from Robinson. Prince George married a widow, Maria Fitzherbert (d. 1837), without his father's consent in 1785. The fact that Maria was a Catholic meant that in English law, as stipulated in the 1701 Act of Settlement, the prince could not now become king. However, the marriage was considered invalid since it breached the 1772 Royal Marriages Act, which stipulated that any royal marriage where the protagonist was under 25 years of age could only be valid if consent had been given by the reigning monarch. In any case, George did not remain faithful to Maria for long and soon had a mistress, the Countess of Jersey.

The prince's lavish lifestyle had two immediate consequences. The first was that he acquired massive debts – his treasurer once lamented they were "beyond all kind of calculation whatever" (Starkey, 445). The second consequence was that he became seriously obese, so much so, he gained the ignominious nickname of the 'Prince of Whales'. A third, more durable consequence of the Prince's taste for pleasure, was that the coastal resort of Brighton became fashionable, so much time did the prince spend there. The seaside town benefitted from such architectural wonders as the Royal Pavilion, a pleasure dome built in the style of an Indian palace by John Nash (1752-1835) and used as the prince's summer home.

George, appeasing his father's and Parliament's wish for a more respectable and politically useful marriage, wedded his cousin Caroline of Brunswick-Wolferbüttel (d. 1821) on 8 April 1795. The couple did not get on at all, but they did produce the prince's only legitimate child, a daughter called Charlotte Augusta, born on 7 January 1796. After the birth, the royal couple lived permanently apart but never divorced. Princess Charlotte died on 6 November 1817 during a difficult childbirth in which the infant also died.

Prince George had several more mistresses, including the Marchioness of Hertford, but Maria Fitzherbert seems to have been the true love of his life, and he kept her close to him by continually threatening suicide if she stayed away too long. When he became king, George wanted a divorce from Caroline to ensure she did not become queen, and this necessitated a sort of trial in the House of Lords. Ample evidence was found that Caroline had had affairs outside her marriage, but the public's support for her meant that the politicians proved reluctant to take a decision detrimental to their own popularity. The case was dropped. Caroline, still officially married to George, returned to Brunswick in Germany in August 1814.

The Regency

From the late 1780s, King George III began to show signs of mental instability. He often talked incessantly and made wild accusations towards those around him, including the queen. Seemingly unable to control his outbursts, he was once spotted in the park at Windsor talking to a tree in the belief that he was in conversation with the King of Prussia. The king may have been suffering from acute porphyria, a type of liver and blood disorder which affects the brain and nervous system. George did make a recovery, but he had relapses. Around 1810, and perhaps brought on by the early death of his favourite and youngest daughter Amelia aged 27, the king's madness returned worse than ever. The royal doctors were rather limited in their response to the king's distressing illness and did no more than draw blood from his head and restrain him in a straitjacket. On 6 February 1811, as the king was clearly incapable of ruling, his eldest son George, with the consent of Parliament and the Regency Act, was selected to rule as Prince Regent. The king, now with long hair and a long beard, lived the life of a recluse in Windsor Castle as he went blind and almost totally deaf.

The Prince Regent was given the right to fully exercise royal power, such as it was. He remained a constitutional monarch with real political and military power remaining in the hands of Parliament. With the monarchy now as a figurehead of government, the Prince Regent understood the need for public pomp and circumstance. A visit by the newly restored Louis XVIII of France in 1814 was the cause for a public procession and gala. Then, later that summer on 1 August, the centenary of the Hanoverians on the British throne was celebrated in lavish style. The public was entertained with fun parks, fireworks, and a mock naval battle on the Serpentine in Hyde Park.

The Napoleonic Wars

Prince George had to face a crisis immediately, the ongoing conflict which became known as the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15). The conflict pitted Britain and a whole host of European allies against its old enemy France, led by Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), with Spain and Prussia as his allies, amongst others. Britain won the decisive Battle of Trafalgar off the coast of Spain on 21 October 1805, where the Royal Navy was commanded by Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson (1758-1805). Lord Nelson died at the moment of victory, but Trafalgar meant that the Royal Navy essentially stood unchallenged to police and expand the British Empire for the next 100 years. The long-term and substantial investment in shipbuilding and ships under the Hanoverians had paid off spectacularly.

On land, meanwhile, Napoleon achieved dominance in Continental Europe, but he was ultimately defeated at the Battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815. The British were commanded by Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington (1769-1852) at Waterloo (in today's Belgium). Helped by their Prussian allies, the victory that ended the Napoleonic Wars was a high point in British military history. The Prince Regent commented that: "It is a glorious victory and we must rejoice at it. But the loss of life has been fearful" (Phillips, 201). Around 40,000 men on all sides were killed or wounded in the battle. Napoleon abdicated as Emperor of France, and he was exiled to the remote island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic. The wars had been extraordinarily expensive, and the costs were met by the taxpayers, which did not endear George to his subjects, especially as his great debts and high spending on palaces were common knowledge.

Succession

Queen Charlotte died in 1818, and then George III died of pneumonia on 29 January 1820 at Windsor Castle. The Prince Regent, already 58 years old, became George IV of Great Britain and Ireland, and like his predecessors, he took on the title of King of Hanover. His extravagant coronation ceremony – 25 times more expensive than his father's – was held on 19 July 1821 in Westminster Abbey. The king's legal wife Caroline was not invited to the coronation, and the doors of the abbey were even locked and guarded by hand-picked prizefighters to keep her out, although that did not stop her travelling to England and trying to get in anyway. Caroline died suddenly of an illness shortly after the ceremony on 7 August. On the almost-queen's coffin were inscribed the words: "Caroline of Brunswick, the Injured Queen of England" (Ralph Lewis, 205).

George at least made sure he corrected the errors of his Hanoverian predecessors, and he visited Scotland, Ireland, and Wales during his reign. The king's trip to Scotland in the summer of 1822 was the first by a reigning monarch in 171 years. It was particularly well-received thanks to the famed novelist Sir Walter Scott's direction of the whole affair and the king embracing Scottish Highland culture to the point of even wearing a kilt, a decision which began a fashion for tartan south of the border. Back home, the monarch's trips away and his lack of interest in politics and day-to-day governance meant that the power of the monarch further dwindled during his reign while the powers of Parliament and the prime minister increased.

The Arts & Architecture

George IV may not have excelled at politics – he himself rued that "playing at king is no sinecure" (Starkey, 446) – but he did certainly make his mark in the arts. George was an avid art collector, and in his lifetime, he added many masterpieces to the already magnificent Royal Collection. George acquired paintings by Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) and Rembrandt (1606-1669), amongst many others. Sculpture was not neglected, and George commissioned Antonio Canova (1757-1822) to create Mars and Venus, a large piece which today stands in the Grand Entrance and Marble Hall of Buckingham Palace. The king also helped found the National Gallery in 1824.

The decorative arts now began to utilise elements seen in other cultures as contact between Britain and the rest of the world increased. A distinct design style known as the Regency style developed (which actually covers the period of George's reign as king, too) where designers added to the well-established Georgian style various decorative motifs and materials inspired by Classical, Chinese, and ancient Egyptian art.

Literature continued to blossom in both the Regency period and George's reign proper. Two notable female authors made a lasting impression on readers: Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice was published in 1813 and Mary Shelly's Frankenstein came out in 1818. When Austin discovered that George had a set of her books in each of the royal residences, she dedicated her next novel Emma to the Prince Regent. George's interest in reading was further evidenced in 1820 when he founded the Royal Society of Literature.

Architectural developments continued as the Georgian period went on. The rather austere style of this period, which modestly reimagined elements of Roman and Greek architecture but then added an eclectic sampling of other more flamboyant architectural styles like Gothic and Indian, became known as Regency Architecture. George IV sponsored the development of Regent Street and Regent's Park in London, the idea being to have fine houses in a rural-garden setting, and these are typical examples of Regency Architecture. John Nash, the designer of the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, was behind these projects, too. Canal-building was another major project of this period. Finally, the king also spent a great deal of time and money improving Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle.

Death & Successor

George IV, still a great overeater and drinker but now heavily dependent on laudanum, died of a ruptured blood vessel in his stomach on 26 June 1830 at Windsor Castle. The king was buried in St. George's Chapel in Windsor. The unpopular king was not missed by many, as The Times newspaper stated: "There was never an individual less regretted by his fellow creatures than this deceased King" (Cavendish, 384).

With no legitimate surviving children of his own, George was succeeded by his 66-year-old younger brother William, Duke of Clarence, who became William IV of Great Britain. King William, also without any legitimate children of his own, was succeeded by his niece Queen Victoria (r. 1837-1901), daughter of George III's son, Edward, Duke of Kent (1766-1820). Victoria was the last of the Hanoverians as her children were classed as part of the new dynasty of Saxe-Coburg & Gotha (which was later renamed Windsor).