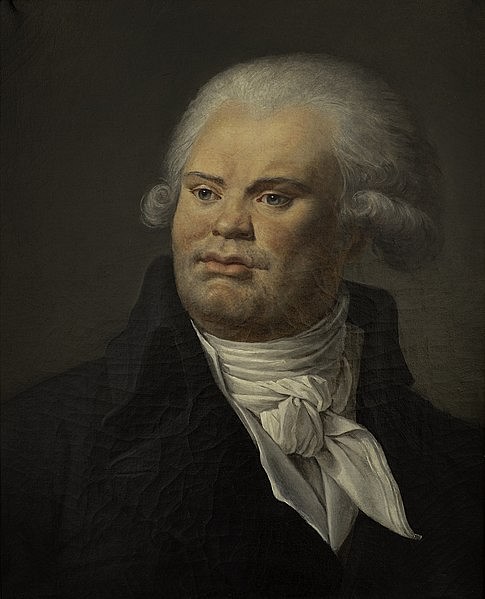

Georges Jacques Danton (1759-1794) was a French lawyer who became a prominent leader of the French Revolution (1789-1799). Danton played a major role in the overthrow of the French monarchy and the subsequent establishment of the First French Republic. He eventually took a moderate stance and opposed the Reign of Terror, leading to his execution on 5 April 1794.

Pre-revolutionary Life

Danton was born in Acris-sur-Aube, a commune in northeastern France, on 26 October 1759 to an ordinary bourgeois family that had only recently risen from the peasantry. He was the son of lawyer Jacques Danton and his second wife, Marie-Madeleine Camus, and had an elder sister Anne-Marguerite. When Danton was three, his father died, and his mother remarried in 1770 to a grain merchant. During his childhood, Danton's face was scarred by a smallpox attack and by some unfortunate encounters with farm animals: he was stampeded by pigs and kicked in the face by a bull, leaving him permanently disfigured.

Beginning in 1773, he was educated at a religious college in Troyes. In 1780, he went to Paris where he found a job as a law clerk, and by 1784, he was pursuing a law degree at Reims; he maintained his clerk position and often travelled between Paris and Reims. Danton often stopped for refreshments at the Café du Parnasse, opposite the Palais de Justice in Paris, and it was here that he met and fell in love with Antoinette-Gabrielle Charpentier, the owner's daughter; the two were married on 14 June 1787. That same year, Danton borrowed enough money to purchase the venal office of advocate in the Conseil du Roi. This was a council with legislative and judicial functions, offering Danton a bright future.

The Dantons settled into a six-room apartment in the Left Bank in Paris and had three sons, two of whom lived to adulthood. Danton seemed set to live a moderately successful, if perfectly obscure, life. Yet even then, the storm clouds of revolution were gathering; the poor were starving, the social orders were bickering, and a mountain of state debt threatened to smother all of France beneath its weight. In May 1789, King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) had no choice but to convene the Estates-General of 1789 to try and sort out these issues; the meeting backfired when the estates coalesced into a National Constituent Assembly and defied royal authority by promising to write a new French constitution. The king's attempts to restore order through force of arms led to the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July by the people. The French Revolution had begun, and Danton's life would soon become completely entwined with it.

The Revolution Begins

In the words of French historian Mona Ozouf, Danton was "a creation of the Revolution" who "emerged unheralded out of the great event itself" (Furet, 213). On 13 July 1789, amidst the riots that led to the Bastille's fall, Danton forced his way into the pages of history when he stood atop a table and urged his fellow citizens to action. Tall and athletic with a deep and booming voice, he was impossible to ignore. Two days later, he volunteered to join the National Guards of his district and quickly became enmeshed in local revolutionary politics.

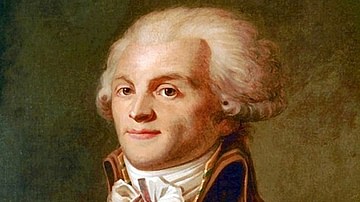

The district where Danton lived, centered around the old Cordeliers convent, was a hotbed for radical revolutionary activity. Danton lived just around the corner from up-and-coming revolutionaries Camille Desmoulins (1760-1794) and Jean-Paul Marat (1743-1793). The three likely became acquainted at the Café Procope, where the revolutionaries of the Cordeliers district gathered to drink and share their visions for a better France. Danton's charisma and revolutionary zeal helped him stand out amongst this crowd, and he was elected president of the Cordeliers district in early October. He became a spokesman for popular radicalism, denouncing the moderate policies of Paris mayor Jean Sylvain Bailly and Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834). He frequented the Jacobin Club, a political society where revolutionaries met to discuss their agendas, and soon became one of its foremost members alongside Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794) and Jacques-Pierre Brissot (1754-1793).

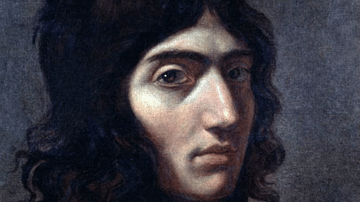

Danton's oratory abilities earned him the nickname "Mirabeau of the gutter", after the eloquent revolutionary leader Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau (1749-1791), who shared many qualities with Danton. Like Mirabeau, Danton was an electrifying and passionate speaker, whose unique appearance only added to his magnetism. Like Mirabeau, Danton was no stranger to vice and was known for his womanizing and heavy drinking. Like Mirabeau, Danton faced accusations of corruption. Yet unlike Mirabeau, an ex-nobleman, Danton was thoroughly a man of the people and closely identified himself with the plight of the sans-culottes, Revolutionary France's lower classes.

Cordeliers Club

In April 1790, the Cordeliers district was abolished due to redistricting, and Danton lost his public office. To keep the area's revolutionary flair alive, Danton and Desmoulins founded a new political club, which took its name from the Cordeliers convent in which it gathered. The Cordeliers Club kept its membership fees low, at only one penny a month, so anyone could attend; this inclusivity set it apart from most other political clubs, like the Jacobins, which catered to a mostly bourgeois crowd. The Cordeliers met every morning at 9, and Danton arrived promptly, taking his position amongst the throngs of working-class attendees. He was made the Cordeliers' first president on 27 April 1790.

In June 1791, Louis XVI and his family attempted to flee France in their ill-fated flight to Varennes. This disturbed much of the French population, who believed the king had been attempting to instigate counter-revolution. In July, the Cordeliers Club led the call for the king's deposition; Danton, Desmoulins, and Brissot prepared a petition that called for Louis XVI's abdication and for a referendum to be held to decide the monarchy's future. When demonstrators gathered on the Champ de Mars to sign the petition on 17 July, they were fired on by National Guards commanded by Lafayette, causing 50 deaths. After the Champ de Mars Massacre, the National Assembly clamped down on agitators, forcing Danton to flee to London for a month to avoid arrest. Interestingly, his name appeared nowhere on the petition he had been pushing, nor was he present on the day of the massacre, causing his enemies to doubt his motives.

Overthrow of the Monarchy

In 1792, France declared war on Austria, sparking the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802). The war began badly for the French, who were pushed back from the frontier, allowing a Prussian-led army to begin a slow march toward Paris. Danton, who had been hesitant to support the initial declaration of war, became a vigorous supporter of the war effort, realizing that a defeat would spell an end to the Revolution. He continued denouncing Lafayette, now a general in command of a French army, who Danton believed would use his position to play politics. When Lafayette fled France after failing to garner support for a coup against the Jacobins, Danton appeared vindicated in his suspicions, and his popularity only increased.

Meanwhile, many revolutionaries suspected the king of being ambivalent toward the defenses of France, or even of aiding France's enemies. In late July, the invading army issued the Brunswick Manifesto, which threatened to destroy Paris should any harm come to the French royal family. This threw the city into a panic, and the sections of Paris began to plan an insurrection against the traitorous king. Much of the planning took place within the Cordeliers Club, and Danton took a leading role in the insurrection's organization. As the date of the insurrection drew nearer, Danton went home to Acris-sur-Aube and gave all his money to his mother in case he was killed. Back in Paris, he and his wife Gabrielle spent the evening of 9 August dining with Desmoulins and his wife Lucile; after the meal, the two men grabbed their rifles and went off to join the insurrectionists, leaving their wives behind in tears.

In the small hours of the morning of 10 August, Danton led men from all 48 of Paris' sections to the Hôtel de Ville, the seat of city government, and installed themselves as an Insurrectionary Commune with Danton as the minister of justice. His first action was to order the arrest and execution of Marquis de Mandat, commander of the National Guard, who had expected the insurrection and organized defenses against it. Then, the insurrectionists set out for the palace itself, beginning the Storming of the Tuileries Palace. Throughout the day, a bloody battle raged as the insurrectionists fought the Swiss Guards, resulting in 800 dead. Yet, by the morning of 11 August, it was clear that the Insurrectionary Commune ruled Paris. The Commune demanded the king and queen be imprisoned in the Tower of the Temple, and the National Assembly had no choice but to oblige. For all intents and purposes, the French monarchy was dead.

Insurrectionary Commune

As minister of justice for the Insurrectionary Commune, Danton held the power of the city in his hands. He authorized commissioners to search every house or apartment belonging to someone suspected of royalist sympathies or counter-revolutionary intentions. By the end of the month, Paris' prisons were bursting with thousands of suspected traitors; meanwhile, the guillotine was set up on the Place de la Revolution and was used to execute condemned political prisoners for the first time.

On 30 August, the invading Prussian force laid siege to the critical fortress of Verdun. Danton, who had taken on the responsibility for the city's defenses, called for 30,000 National Guards and volunteers to be sent to the front. Yet the people were hesitant to go, fearing a royalist plot to free thousands of prisoners in their absence, who would then go on to destroy Paris. On 2 September, news reached the capital that Verdun had fallen; panicked and enraged, mobs of Parisians made their way to the city's prisons where they proceeded to butcher counter-revolutionary prisoners. The murders went on for five days, and 1,100-1,400 people were killed. While Danton did not orchestrate the September Massacres, as his enemies would later claim, it is true he did nothing to stop them. Instead, he spent his efforts urging the citizens to the defense of the fatherland, issuing his most famous speech on 2 September: "If we are bold, bolder still, and forever bold, then France is saved!" (Doyle 191).

Such boldness would soon pay off. On 20 September, a French army halted the Prussian invasion at the Battle of Valmy; the next day, the French Republic was proclaimed. The French then pushed into Belgium, capturing it after their victory at the Battle of Jemappes. Danton was one of the leading voices calling for Belgium's annexation, believing that the borders of the French Republic were "mapped out by nature" and should be extended all the way to the Rhine. He was a fervent supporter of French expansionism, stating, "we have the right to say to other nations, you shall have no more kings" (Furet, 219).

Committee of Public Safety

In February 1793, Danton was on mission in Belgium, working towards its annexation, when he received news that his wife Gabrielle had died giving birth to their fourth son, who had also died. Danton rushed back to France, only to find that his wife had already been four days buried; in the dead of night, he exhumed her corpse so he could look upon her one last time, and commissioned a sculptor to come out to the graveyard to make a bust of her. Five months later he remarried to Louise Sébastienne Gély, the 16-year-old daughter of one of his Cordelier friends, though he never seemed to get over his first wife's death.

Meanwhile, the war had again turned against the French. The Coalition had retaken Belgium, and French General Charles François Dumouriez had defected to the Austrians. This painted Danton in a suspicious light; only days before Dumouriez's treason, Danton had visited the general, a fact that the Girondin political faction used to accuse Danton of aiding him. Around this time, Danton was also accused of corruption. He had paid off the debts incurred by purchasing his advocate office startingly fast and had bought national properties with cash that seemed to appear out of thin air. He refused to provide the receipts for these transactions, something his enemies quickly latched onto.

In the spring of 1793, tensions increased between the Girondins and Danton's own political faction, the Mountain. Danton became convinced that blood would soon be spilled; if Terror was inevitable, Danton believed it was better for the government to control it lest vigilante justice be carried out by unruly mobs. "Let us be terrible," he said, "in order to dispense the people from being so" (Furet, 220). In March 1793, he played an instrumental role in the establishment of the Revolutionary Tribunal, and the following month he helped create the Committee of Public Safety, a committee meant to oversee the nation's defense, of which he was the first member. Thus, Danton played a major role in laying the groundwork for the Reign of Terror, which he would soon regret.

As the dominant member of the Committee of Public Safety, Danton backpedaled away from his expansionist rhetoric from the previous autumn. The preservation of the Republic was his top priority, and so he began to pursue means of peaceful negotiation with the nations of the anti-French coalition. This defeatist foreign policy won him no friends, and on 10 July, he was voted off the Committee. Taking his place was Robespierre, who led the Committee in a more radical direction and slowly accumulated greater powers. During the insurrection of 5 September, Danton spoke in favor of giving in to the mob's demands, including arming all citizens and forming a revolutionary army to maintain the Republic's authority in the countryside. He refused an offer to be reinstated on the Committee of Public Safety, which was becoming too radical for his liking.

Indulgents

Late 1793 saw the Terror accelerate; tens of thousands of counter-revolutionary suspects were arrested, many of whom faced sham trials before the Revolutionary Tribunal Danton had helped to create. The trial of the Girondins, who had once been Danton's friends even if he came to oppose them politically, especially upset him; "I shall not be able to save them!" he lamented to a friend through tears. Weary of the politics and the bloodshed, he abruptly left Paris on 12 October, returning to his hometown with his wife and children. He stayed for over a month before returning to Paris on 21 November; afterwards, he became the leader of the moderate Indulgent faction, which advocated for scaling back the Terror.

Danton's moderatism brought him into conflict with Jacques-René Hébert, an “ultra-revolutionary” journalist who sought to further intensify the Terror and who had usurped Danton's old Cordeliers Club. Desmoulins, who was once again acting as Danton's righthand man, published Le Vieux Cordelier ("the Old Cordelier") a newspaper attacking the Hébertists and the excesses of the Terror. The paper was initially published with the blessing of Robespierre, who also despised the Hébertists; but when Desmoulins began using his paper to criticize Robespierre's own terroristic policies, Desmoulins was kicked out of the Jacobin Club. The Indulgents and the Robespierrists were now on a collision course.

Danton's position was not helped when his close friend and supporter Fabre d'Églantine was arrested in January 1794, in connection to a corruption scandal surrounding the French East India Company. When Danton came to his friend's defense, he was accused of having been complicit in the scandal himself. Sensing a weakness, Hébert increased his attacks on the Indulgents, hardening the radicals' hearts against them, until Hébert and his allies were executed in March 1794. With the Hébertists gone, the Indulgents became the biggest threat to Robespierre's authority; warned several times that he was in danger of being arrested, Danton laughed it off, proclaiming, "they will not dare!" But on the night of 29-30 March, Danton, Desmoulins, and other Indulgent leaders were arrested.

Trial, Execution, & Legacy

From 2-4 April, Danton was tried before the Revolutionary Tribunal. The throngs of spectators who packed the courthouse were a testament to his enduring popularity. He put on one final, memorable show, thundering on about his patriotism and the injustice of his trial until he was ordered to be silent. On 5 April 1794, Danton was the last of 15 to be guillotined, a group that included Desmoulins, Hérault de Séchelles, Fabre d'Églantine, and Pierre Philippeaux. After watching the executions of his closest friends, Danton himself went below the blade. "Show my head to the people," he told the executioner. "It will be worth seeing" (Davidson, 216).

Immediately after his death, Danton was vilified by Robespierrists, who emphasized his corruption and used his venality as proof that he was never a true patriot. This remained his legacy for almost a century until the French Third Republic needed to dig up patriotic heroes from France's republican past in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71). Danton was an obvious candidate for national heroism, due to his commitment to the defense of the French First Republic. As Danton left behind few written records, his true thoughts and opinions will never be known and have long been debated by scholars. Yet his larger-than-life presence profoundly affected the French Revolution, on which he left his unmistakable mark.