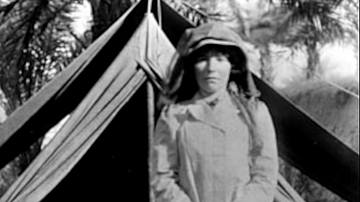

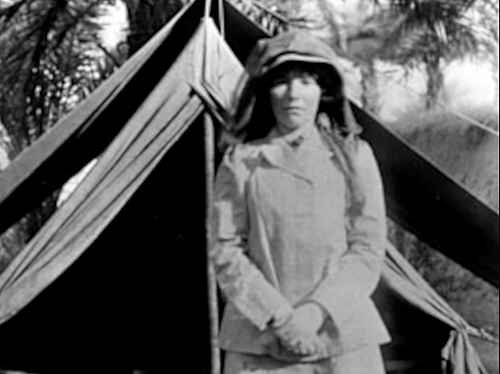

Gertrude Bell (l. 1868-1926) was an archaeologist, travel writer, explorer, and political administrator responsible for creating the borders of the countries of the Near East after World War I and, especially, for the foundation of the modern state of Iraq. She is still widely respected though the partitioning has been criticized as an exercise in Orientalism.

Orientalism is a term coined by Professor Edward Said (l. 1935-2003) referring to the Western view of the East as inferior and Eastern peoples as less capable of self-determination than those of the West. This understanding, according to Said, justified Western Imperialism in the East up through the 20th century. Bell’s involvement with the partitioning of the Near East in the 1920’s has been cited as an example of this concept in action as the British did not believe the people of the region capable of self-government.

Although Bell made important contributions to archaeology and a greater understanding of the cultures of Mesopotamia and ancient Persia through her books, including what is still considered the best translation of the Persian poet Hafiz’s work, she is best remembered for the part she played in the Near East partition. Interestingly, she has been criticized more by Western writers than those of the East who generally recognize her efforts to establish a free and independent Arab state in the region. Even today she is remembered as al-Khatun, the lady of the court who advised the king.

Early Life, Education, & First Love

Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell was born 14 July 1868 at Country Durham, Washington, England. Her grandfather was the industrialist and politician Sir Isaac Lowthian Bell who established the family fortune, and her father was Sir Hugh Bell (l. 1844-1931), an intellectual and liberal-minded industrialist who mandated fair wages and paid sick days for his workers. Her mother was Maria Shield who died in 1871 after the birth of their second child, Maurice.

After her death, Sir Hugh married Florence Olliffe (l. 1851-1930), the British playwright and author, with whom he would have three more children, Hugh, Florence, and Mary. Bell was close with both her father and stepmother throughout her life, corresponding with them both almost daily.

As a young girl, Bell was described as “high spirited” by her stepmother who noted that when she wasn’t reading or writing she was engaging in various “naughty behaviors” such as climbing steep cliffs or scaling other heights. She seemed quite different from the girls she associated with and so her parents decided to treat her accordingly. Scholar Janet Wallach writes:

No matter how bright they were, girls of Gertrude’s class rarely were sent away to school; instead, they were tutored at home and, at the age of seventeen, were presented at court and introduced to society. Within three seasons of coming out, each was expected to find a husband. But Gertrude had shown an exceptional mind, too keen to be kept at home. Florence and Hugh, progressive thinkers both, took the radical step of sending her to a girls’ school in London. It would calm the energy level of the household and, at the same time, feed Gertrude’s hungry intellect. Queen’s College, a girls’ school on Harley Street, was started in 1848 as a series of Lectures for Ladies. (15)

Bell was unhappy at first to be sent away but quickly took to life at school and exceled at her studies. She asked her father to be allowed to continue her education at Oxford University, which had only recently allowed for a program including females, and he agreed she should attend. Bell would be the first woman to graduate at Oxford in the history program in 1888 though this was considered an honorary degree, not academic, as she was a female.

She traveled to Bucharest with her uncle, Sir Frank Lascelles, and his family later that year and then to Paris and other points around Europe before leaving England to join Lascelles in Persia (modern-day Iran) in 1892 where he had been given the post of British Minister in Tehran. At this point she studied Arabic and Persian, having already mastered several other languages including French and German.

In Tehran she met Henry Cadogan, one of her uncle’s secretaries, and bonded with him over a love of the poetry of Hafiz. Cadogan seemed her intellectual equal and they spent significant time together before announcing they were engaged. Bell wrote letters home asking for her father’s permission to marry but this was denied. Cadogan came from a poor family and, as Bell herself noted, even though her father would have loved to have been able to agree to the match, he could not afford to support another household when he was already responsible for his own.

Bell returned to London, still hoping to win her parents’ approval of the match, and there received the news that Cadogan had died of pneumonia (not by suicide, as suggested by some writers and the 2015 film Queen of the Desert) in 1893. Bell was heartbroken and left England to travel in Italy and Switzerland where she became an adept Alpine climber, once surviving over 48 hours clinging to a rope on the side of a cliff.

Travel & Archaeology

In 1897, with her younger brother Maurice (with whom she was very close), Bell embarked on a world tour, visiting Mexico, the United States, Japan, China and other points east, returning by way of Egypt, Greece, and Turkey to England. On a trip to Italy with her father in 1898, she met the archaeologist David Hogarth and began an in-depth study of Greek antiquities.

She traveled from Italy to Turkey, through Prague and then Germany before moving to Jerusalem to stay with the Rosens (family friends stationed at the German Consulate there) before moving on to visit ancient sites in Syria, Lebanon (stopping at Baalbek), and Athens while studying Hebrew and improving her Arabic. In 1899 she left Jerusalem for her first solo journey through the desert during which she photographed ancient sites such as Petra, Palmyra, and Baalbek before returning to England.

By 1901 she had mastered photography and developing and would afterwards always bring her camera and photographic equipment on travels, capturing images of ancient sites still valuable to archaeologists and scholars in the present day. In 1904, her grandfather died, leaving her a large inheritance which she used to fund an archaeological trip throughout the Near East. In 1905 she hired the man who would become her main guide and confidante on future journeys, Fattuh, who helped with the latter part of this trip before she returned to England to begin writing The Desert and the Sown which introduced the larger world to ancient sites and the people of the regions she had traveled through.

Returning to the Near East in 1907, she worked with the archaeologist and scholar Sir William Ramsay in Binbirkilise (whom she describes as a kind of “absent minded professor” archetype) and met the British officer Charles “Richard” Doughty-Wylie (l. 1868-1915), a married man she fell in love with. The two never acted upon their feelings for each other but kept up a correspondence, which is preserved, clearly expressing the depth of their devotion to each other. Doughty-Wylie is best known, outside of his relationship with Bell, for his efforts to stop the Armenian Genocide in its earliest phase and organizing the relief of over 20,000 Armenians targeted by the Turks for execution.

The two parted ways but remained in touch and their correspondence touches on several historical events between the time they met and his death including her meeting a young T. E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”, l. 1888-1935) at Carchemish in 1909. She was deeply impressed at this time by the work of the art historian Josef Strzygowski (l. 1862-1941) who maintained that European art and architecture was influenced by that of the Near East and so were religious and cultural concepts. Bell worked with Strzygowski in writing about this regarding Armenian architecture’s influence on European buildings.

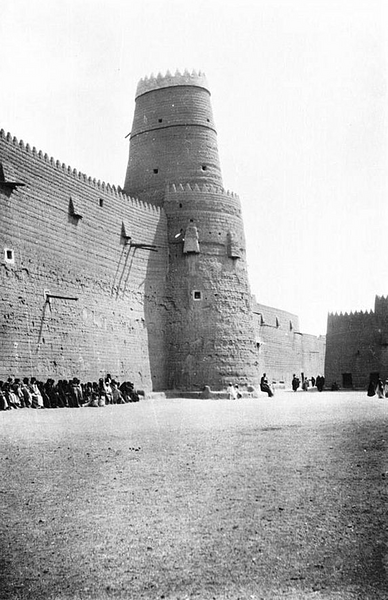

In that same year, the work she co-wrote with Ramsay, The Thousand and One Churches, based on their excavations, was published and, still in 1909, Fattuh, led her to the Fortress of Al-Ukhaidir (c. 750-775 CE, near Karbala, modern-day Iraq) which no Western explorer had yet seen. Bell mapped, sketched, measured, and photographed Ukhaidir and wrote home in great excitement that her discovery would make her a name as a recognized archaeologist.

On her way back, she stopped at Babylon where the German archaeologist Robert Koldewey (l. 1855-1925) was working with his team. She admired their methods, which she found much more efficient than others she had witnessed. She told the team about her work at Ukhaidir and, after she went on her way, several of them quickly went to the site, mapped and photographed it, and scooped Bell on the discovery by publishing their work in 1912 before she could prepare and publish hers in 1914.

In 1913, Bell traveled to the city of Hayyil, against the advice of others, to meet Ibn Rashid and was held for eleven days against her will (for reasons she never discloses nor seems to understand herself) before being released. She traveled through Iraq and Syria, taking notes and photographs for another book, before returning to England shortly before the outbreak of World War I in August of 1914.

Red Cross & Government Work

Bell contributed to the war effort as a Red Cross volunteer first in England and then France. Her brother Maurice was deployed to the Western Front, and she received word from Doughty-Wylie, now a lieutenant-colonel, that he would be commanding the troops at Gallipoli. He was killed in action 26 April 1915 and Bell was deeply affected by his death. Months later, in November of 1915, it was reported that a lone woman arrived at the beach to place a wreath on Doughty-Wylie’s grave. This has been assumed to have been his wife but modern scholars, including Georgina Howell, claim this was Bell who would have had the resources and experience to make the journey.

After Doughty-Wylie’s death, Bell threw herself into her work but was called to Cairo to help with British Military Intelligence there because of her extensive knowledge of the region. In 1916 she was working for the Arab Bureau first under Sir Gilbert Clayton (l.1875-1929) and then Sir Percy Cox (l. 1864-1937). In her capacity as an intelligence officer, Bell was among the first to report on the Armenian Genocide of 1915-1916 which Doughty-Wylie had tried to prevent.

The Ottoman Empire, which was carrying out the genocide, had joined with Germany as one of the Central Powers against the Allies and had ordered the construction of the Hijaz Railway to enable swift troop movements between Mecca and Damascus. The Arab leader Sharif Hussein bin Ali, Emir of Mecca, had been trying to rally his people against the Young Turks since 1908 as he had seen the government ban Arab cultural institutions, outlaw the language, and arrest Arab nationals.

Sharif Hussein was contacted by the British in 1915 and promised arms and advisers if he would lead a revolt against the Ottomans and, after the war was won, an independent Arab state would be formed. Sharif Hussein agreed, and the British sent T. E. Lawrence who helped conduct a guerilla war against the Turks, focusing on the railway, launched as the Arab Revolt on 5 June 1916. Later reports credit Lawrence’s and Hussein’s success to intelligence on the region provided by Bell. Wallach writes:

David Hogarth would later credit Gertrude Bell for much of the success of the Arab Revolt by providing the “mass of information” about the “tribal elements ranging between the Hijaz Railway and the Nefud.” It was this information, Hogarth emphasized, which “Lawrence, relying on her reports, made signal use of in the Arab campaigns.” (202)

On 10 March 1917, the British forces took Baghdad and Bell was called by Cox to join him there in the position of Oriental Secretary. Owing to her fluency in the language and knowledge of the culture, history, and people of the region, she would act as liaison between the British and the soon-to-be-established government of an independent Arab state.

Establishing Iraq

At this time, neither Bell nor anyone else was aware of the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 between Great Britain, France, the Kingdom of Italy, and Imperial Russia dividing up the Near East between them and ignoring the promises made to Sharif Hussein and his people. This would only be disclosed by the Russians after the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917.

The United States had joined the war on the side of the Allies in April 1917, was also ignorant of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, and fought with the general understanding of an autonomous Near East after the war’s conclusion. This same year, however, Foreign Secretary for Britain, Arthur Balfour, issued the Balfour Declaration promising Palestine (at that time part of Transjordan) to the Zionist movement as an autonomous Jewish state. Sharif Hussein had been led to believe he would receive Palestine while the French thought it would be theirs according to the Sykes-Picot Agreement and the Zionists claimed it as their own as per the Balfour Declaration.

The United States supported the Declaration, but Bell rejected it and the Sykes-Picot Agreement, arguing for the free Arab state promised to Hussein and leaving Palestine in Arab hands and Lawrence agreed with her. Even so, the Balfour Declaration was approved in October-November 1917 and Bell was shortly afterward admitted to hospital with exhaustion. World War I ended in November 1918 and Bell was assigned the difficult task of sorting out the “Middle East Problem” to everyone’s satisfaction. In 1919 she wrote up an official report, “Self Determination in Mesopotamia” which detailed the creation of the independent state of Iraq, but British officials did not believe the people were capable of self-government.

The British – and now also the French, Italians, and Americans – were interested in a government that would be compliant with Western interests. The people of Iraq were not interested in their interests, however, triggering the Iraqi Revolt of 1920, uniting the people of the region to throw off foreign rule. In an attempt to fix the problem, Bell and T. E. Lawrence, who had spent the greatest amount of time among the people, suggested Faisal bin Hussein (r. 1921-1933), son of Sharif Hussein, noting that he was not only the son of the war hero to whom promises had been made but would be able to unify the new nation because he was of the royal Hashemite family, was a Sunni Muslim, but was descended of Shia Muslims.

This recommendation was approved at the Cairo Conference of 1921, and it became Bell’s responsibility to groom and advise Faisal I on how to govern. She also encouraged him to devote energies to preserving the vast history of Mesopotamia and, in 1922, helped him to establish the Baghdad Antiquities Museum (now the Iraq Museum) with the initial artifacts donated from her private collection. The people greeted her respectfully as al-Khatun, adviser to the king, but she was more than that as she had actually created both the king and his government. Bell drew the boundaries of the new country, established those of Jordan and Saudi Arabia, and advised Faisal I to the point of frustration before returning to England, now suffering severely from various health problems, in 1925.

Conclusion

She returned to Baghdad later that year but stayed out of politics, claiming it was all too exhausting. In June of 1926 she presided over the opening of the first room of the Antiquities Museum and, that same month, entertained her long-time friend Vita Sackville-West at her home. On 11 July she retired early after giving her maid instructions when to wake her in the morning and, on the 12th, was found dead in her bed of an overdose of sleeping pills. The official report stated the overdose was accidental, citing her instructions to the maid, but privately it was understood she had committed suicide.

Whether this is the case is unknown, but she suffered from depression throughout her life and photos of her often suggest a deeply unhappy woman despite her many significant achievements. She was buried in the British Cemetery in Baghdad and her funeral was attended by hundreds of people who came to pay their respects to the woman they had come to regard as al-Khatun, the Great Lady of the Court.

Although her work in the partitioning of the Near East has been criticized as epitomizing the concept and practice of Orientalism, and Bell herself agreed (privately, at least) that the people would benefit from the “civilizing” influence of a British model, she remains respected for her efforts to be true to the land and people she had come to love.

Bell was both admired and resented by many notables of her time including T.E. Lawrence and the English writer-explorer Freya Stark (l. 1893-1993) who refused to write Bell’s biography and call any more attention to her. Bell is often described as abrupt, arrogant, and contrite but also as generous, eloquent, and always eager to learn and teach.

Her works continue in print and are referenced by modern-day Orientalists and other scholars regularly. Recent testimonies to the enduring interest in Bell are the films Queen of the Desert (2015) and Letters from Baghdad (2016) as well as books, articles, and even graphic novels all of which try, and only partially succeed, in telling the story of the brilliant and complex Gertrude Lowthian Bell.