The Gestapo was the secret political police organisation of Nazi Germany. Created in 1933, the Gestapo became one of the most feared instruments of state terror, its members having few or no legal restrictions to their actions. The Gestapo arrested, interrogated, assaulted, imprisoned, and executed hundreds of thousands of people across Europe ranging from Jewish civilians to Allied prisoners of war.

Origins & Structure

The Gestapo was the organisation that Hermann Göring (1893-1946) formed to replace the Prussian political police in 1933. The name Gestapo, coined in 1933 by a clerk, derives from Geheime Staatspolizei (GEheime STAatsPOlizei), meaning state secret police. With Göring still as the figurehead, the first administrative chief of the Gestapo was Rudolf Diels (1900-1957), a civil servant who actually ran the organisation. In 1934, when the Prussian state became fully integrated into wider Germany, the head of the Nazi SS (Schutzstaffel) paramilitary organisation Heinrich Himmler (1900-1945) took over from Göring in terms of having overall responsibility for the Gestapo. The jostling for power within the complex web of Nazi state organisations continued when, in 1936, Reinhard Heydrich (1904-1942), Himmler's deputy, brought the Gestapo into his wider security police organisation known as Sipo (Sicherheitspolizei). In September 1939, a new organisation was formed with Heydrich at its head, the Reich Security Main Office or RSHA (Reichssicherheitshauptamt). The RSHA included the criminal police or Kriminalpolizei (Kripo), the SD (Sicherheitsdienst) intelligence agency, the Gestapo, and a department for foreign intelligence. With the RSHA's integration into the SS, Heydrich became the third most powerful Nazi after the Führer Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) and Heydrich's immediate superior Himmler.

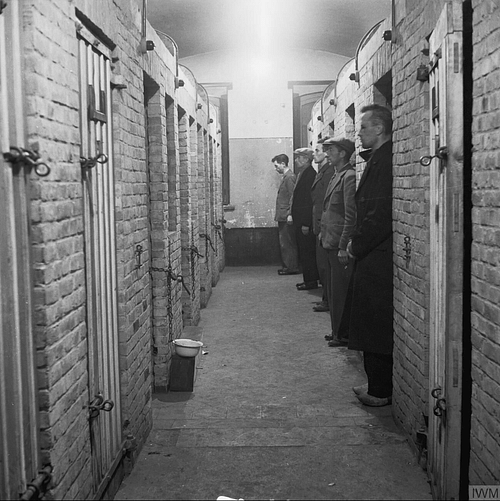

Following Hitler's desire that everyone watched everyone else, the Gestapo ultimately became Department IV of the SS and was also a part of the Reich Interior Ministry. As time went on, the distinction between the functions of the Gestapo and SS became increasingly blurred and overlapping, especially as Himmler steadily replaced veteran police officers inside the Gestapo with SS members personally loyal to him. Department IV was further subdivided into sections. Section IV-A was responsible for dealing with communists, liberals, and saboteurs; it also carried out assassinations. Section IV-B dealt with Jews, Catholics, Protestants, and Freemasons. The head of the Gestapo department from 1939 was Heinrich Müller (b. 1901), a man with long experience in policing and citizen surveillance. The organisation's administrative headquarters and notorious main prison were located at 8 Prinz Albrechtstrasse in Berlin.

Hitler gave the RSHA three main roles: policing and repressing enemies of Nazism, gathering intelligence, and eliminating those people identified by the Nazis as being racially inferior. In none of these roles was the RSHA limited by any legal restrictions. Heydrich's ultimate objective was to have what he described as "total and permanent police supervision of everyone" (Stone, 164), and with the RSHA, he certainly had the tools to achieve this aim. When Heydrich was assassinated by the Czech Resistance in May 1942, Ernst Kaltenbrunner (1903-1946) took over as the new permanent head of the RSHA.

The Gestapo's Purpose

The Gestapo sought out those officially identified as enemies of the Third Reich within Greater Germany. These 'enemies' included Jewish people as loosely identified by the 1935 Nuremberg laws, Romani people, freemasons, communists, habitual criminals, homosexuals, and those with physical or mental disabilities, Other targets included those who used their position to speak out against the Nazi regime, such as priests and intellectuals (including doctors, civil servants, and teachers). When the Second World War (1939-45) began and the German armed forces advanced into new territories, more 'enemies' were added to the list, such as prisoners of war, partisans, former members of local government, and anyone associated with the authority of the previous regime in that territory. It was one of the Gestapo's functions to find these 'enemies', many of whom might be hidden in plain view amongst the rest of the civilian population.

Those identified as enemies of the Third Reich need not have been guilty of any specific crime and they were rarely given any legal representation or means of appeal. In other words, any civilian considered a threat to the Nazi regime's control could be rounded up, imprisoned, sent to concentration camps, and executed without any reason given whatsoever. Those who tried to defend the innocent were very often beaten, imprisoned, or executed themselves. If the state did bother to put people through a semblance of a justice system, the National Socialist People's Court, the highest court for political crimes, heard certain cases. The People's Court had only judges with a distinct Nazi bias, and there were no juries. Defendants had no right of appeal. The People's Court passed nearly 13,000 death sentences between 1934 and 1944. Even those who were found not guilty by the court often found themselves promptly re-arrested by the Gestapo and whisked off to a concentration camp anyway.

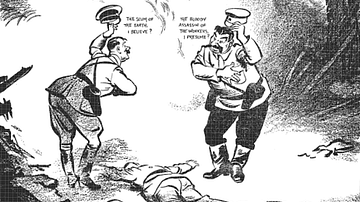

The Fear of the Gestapo

Nazi propaganda ensured that all citizens came to fear the Gestapo whose agents might be anywhere and everywhere. A careless word on a bus, a failure to give the ‘Heil Hitler' Nazi salute at work, or even posting a letter with content criticising the regime or including "defeatist" opinions regarding the war might be picked up by the Gestapo. Other "crimes" included listening to forbidden radio broadcasts or reading blacklisted literature. There were many rules concerning Jewish people after the Nuremberg Laws were passed. Non-Jews, for example, could not form intimate relationships with Jews, they could not listen to music by Jewish composers, and they could not buy from Jewish businesses. Jews were even more restricted in their actions – some of these rules were definite like not being able to appear in public without wearing an identifying yellow star, but others were much more subtle such as the expectation that a Jew must give priority to a fellow pedestrian if they were a non-Jew and so step off the pavement into the road. Such trivialities could be and were reported to the authorities by anyone with a mind to.

Reported individuals had their name and personal details appear in Gestapo files as "Müller card-indexed and colour-coded the nation" (Thomas, 38). Having one's name under a certain category in the Gestapo files could lead to consequences with varying degrees of unpleasantness. People were called into the local Gestapo offices for an interview where they might get away with a mere rebuke. Sometimes the individual came in for subsequent observation or their house was searched by Gestapo agents. Emmy Bonhoeffer recalls the fate of her brother-in-law when he fell into the hands of the Gestapo following a comment he made about the treatment of Jewish people in the Nazi pogrom known as Kristallnacht on 9-10 November 1938:

I remember that the husband of my sister Lena, when he went in the morning after the day of the Kristallnacht, he went by train to his office downtown and he saw that the synagogue was burning and he murmured, "That is an insult for cultured people, an insult to culture." Well, right away a gentleman in front of him turned and showed his Party badge and took out his papers. He was a man of the Gestapo and my brother-in-law had to show his papers, to give his address and he was ordered to come to the Party office next morning at nine o'clock…his punishment was that he had to arrange and to distribute the ration cards for the area beginning of each month for years, until the end of the war.

(Holmes, 42)

For many civilians, their run-in with the Gestapo led to much more serious consequences such as a beating using rubber truncheons or torture where the fingers were crushed using a purpose-built vice. The Jewish diarist Victor Klemperer (1881-1960), who survived the Nazi regime, recorded the following notes in his diary regarding a Jewish friend, Ernst Kriedl, who, like so many others, simply disappeared one day:

November 21 Friday (1941)

Kreidl Sr. summoned to the Gestapo the morning the day before yesterday "for questioning", did not come back. His wife went there in the afternoon: arrest, PPD, in custody, political grounds. No one knows anything more…He is completely harmless…Everyone is threatened by the same fate at any moment.November 23 Sunday

Kreidl Sr. still under arrest, no one knows the reason. Ironic circumstance: He absolutely did not want to go out on the street with the Jew's star, lived at home from September 19. His first walk: ordered to the Gestapo for "questioning." Detained there.November 28 Friday

Kreidl Sr. still under arrest. No one knows what he is accused of. His wife not allowed to speak to him. An inspector at the PPD told her: "He talked." Kreidl's fate...at any hour it could be mine.December 23 Tuesday

Ernst Kriedl is still inside – one has already got used to it (one – but he?), no one asks much about him anymore.

(Klemperer, 445-53)

The Gestapo's ultimate weapon against civilians was to deport them to labour or concentration camps where beatings and the poor sanitary conditions often meant death came sooner rather than later. The Gestapo very often eliminated people simply on the principle that they might become enemies of the state. The "pre-emptive" arrests, and, indeed most arrests, relied upon information coming from informers amongst the general public. Informers might receive a cash reward, but other motivations included self-promotion within the Nazi system or a desire to see a rival removed, or because the informer genuinely believed they were helping rid the state of enemies. Significantly, studies have revealed that in 50 to 80% of cases the Gestapo brought against civilians, the information the secret police had at their disposal and which led them to suspect someone actually came from the public and not their own investigations. Indeed, after the Gestapo became so overwhelmed with citizen denunciations, Himmler was obliged to make it known that those who made unfounded malicious statements would themselves be punished and sent to a concentration camp. Below is an example Gestapo record from July 1940 of one civilian (Maria Kraus) denouncing another (Ilse Totzke):

Ilse Totzke is a resident next door to us in a garden cottage. I noticed the above-named because she is of Jewish appearance…I should like to mention that Miss Totzke never responds to the German greeting [Heil Hitler]. I gathered from what she was saying that her attitude was anti-German. On the contrary she always favoured France and the Jews. Among other things, she told me the German Army was not as well equipped as the French…Now and then a woman of about 36 years old comes and she is of Jewish appearance…To my mind, Miss Totzke is behaving suspiciously. I thought she might be engaged in some kind of activity which is harmful to the German Reich.

(Hite, 205)

The Gestapo was a relatively small organisation within the Nazi state machine, reaching a little over 31,000 members by the close of WWII, and so the organisation certainly needed outside assistance to achieve its objectives. Due to its small number of agents, some modern historians have pointed out that the Gestapo could not have functioned without some degree of cooperation from the general population. Nevertheless, the perception amongst citizens that the Gestapo was everywhere – a perception attested by many after the war – was a triumph of Nazi propaganda. Gestapo agents in their clichéd long black leather coats (which some did wear) were not actually everywhere, but such was the atmosphere of tyranny, most people began to believe the Gestapo really was omnipresent, and even if no Gestapo agent was watching you, it was clear that other citizens certainly were.

The Final Terrors

As the Second World War dragged on and Hitler's fury against his enemies raged ever more fiercer, Gestapo members became involved in such secret operations as the Einsatzgruppen, the killing squads that executed hundreds of thousands of innocent victims across occupied Europe. The Gestapo was heavily involved, too, in the Final Solution, that is, the transportation to and mass extermination of Jewish people in purpose-built death camps like Auschwitz and Dachau.

Prisoners of war were frequently executed by the Gestapo. According to testimony given in the Nuremberg trials, orders were issued that any Jewish or Communist functionaries amongst the prisoners of war taken during the campaign against the USSR were to be executed. Prisoners of war of Asian origin very often received the same treatment. The Gestapo was also responsible for the infamous execution of 50 Allied prisoners of war who had, in an exploit widely known as the ‘Great Escape', tunnelled out of Stalag Luft III in western Poland in March 1944.

The Gestapo also went into overdrive following the 1944 plot to assassinate Hitler, which succeeded only in injuring the Führer. The Gestapo had long practice at ferreting out enemies within the Nazi organisations themselves, starting with the Night of the Long Knives in June 1934, the purge of the SA paramilitary organisation. After the failed assassination of '44, the Gestapo was given free rein to hunt down the conspirators since Hitler was particularly determined on revenge against anyone who had been remotely involved. The Gestapo called the group responsible for the plot the Schwarze Kapelle ('Black Orchestra'), and they arrested not only the conspirators but also the children of the conspirators, anyone who might have been connected to the conspirators but probably was not, and anyone else they simply did not like. Thousands were arrested and either executed or sent to the concentration camps.

The Gestapo organisation collapsed as Germany itself did at the end of WWII, although it was still arresting political suspects right into the final days of the conflict. At the post-war Nuremberg trials, which sought to bring Nazi war criminals to justice, the Gestapo was officially condemned as a criminal organisation. Kaltenbrunner, head of the RSHA, was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity and hanged in October 1946. Müller was reported dead in May 1945, but his body was never positively identified, a fate shared by countless victims of this most brutal of Nazi instruments of terror.