In the canon of the New Testament, the fourth gospel of John is uniquely different from the other three, known as the Synoptics ("seen together"). Mark, Matthew, and Luke have parallel ministries and methods of relating the story of Jesus of Nazareth as an apocalyptic prophet of Israel. John's Jesus is a mysterious theos aner ("man from heaven") whose speeches are framed within the discourse of Greek philosophy.

Like the other three, John's gospel first circulated without a name. This gospel includes a character referred to in the third person, 'the beloved disciple' as an intimate disciple of Jesus. During the 2nd century CE, the Church Fathers claimed that a man known as John the Elder in the community at Ephesus was one of the last living disciples. They claimed that this was 'the beloved disciple,' the brother of James (the two sons of Zebedee), and thus the name.

John is traditionally dated toward the end of the 1st century CE, but not because of any internal dates. The teachings of this Jesus appear to be much more spiritual in the sense of striving for higher concepts of religious experience. It was assumed that the ideas would take time to evolve, and so John is located c. the year 100. This date is now being challenged by some modern scholars.

Christology in John

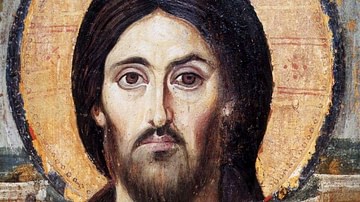

'Christology' simply means "the study of Christ," but it refers to the study of the nature of Christ to address the question of whether Jesus was divine or human. The Synoptic Gospels are described as low Christology – a human Jesus who only became exalted to divinity after his resurrection and ascension. By contrast, John is described as high Christology in his portrayal of Jesus as a pre-existent divinity involved with creation.

One of the reasons that the date of John is being debated is because John's Christology matches that of Paul the Apostle in many respects. Paul's letters date to the 50s and 60s of the Common Era. Paul (who was also educated in Greek philosophy) claimed that Christ was present at creation, but "humbled himself" to take on flesh in order to effect salvation for humans (Philippians 2:8). John's high Christology may reflect a much earlier date for the Christian practice of worshipping Christ as a god or as God himself.

Philosophical Monotheism

The Gospel of John continues to be analyzed in relation to which sources he utilized from the Synoptic Gospels, and which were independent. A major source was his philosophical education. Plato had explored the relationship between humans and the divine (the powers of the universe). He posited the idea of the One, an original ultimate reality, the highest good, which emanated the other powers. A lesser power, the Demi-Urge, created the physical matter of the universe. 'Lesser' in the sense that matter was subject to decay and death and so not the product of the perfect One.

The One, however, remained connected to the universe through a concept known as the logos. Often translated as "word," the logos was the principle of rationality which ordered the universe out of matter and explained universal theories (such as the planetary rotation, gravity, and the ordering of plants, animals, and humans). In the 1st century CE, a Jewish philosopher in Alexandria, Philo, attempted to reconcile Judaism with Greek philosophical claims. He had explained that Moses served as the logos for Judaism. Moses provided the formal structure and law codes for the Jews as a nation.

The Preface of John

In the beginning was the Word [logos], and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. ... Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made. ... The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the one and only Son, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth. (John 1:14)

The opening of John contributed to the doctrine of Christianity known as the incarnation. From carnal in Latin meaning "flesh," it was understood that Jesus was not born in the traditional manner. As the original logos, he "took on flesh," a physical body, simply to communicate with us.

In the 2nd century CE, Christian bishops utilized John's doctrine of the logos to argue that Christianity taught the very principles as all the schools of philosophy. In other words, Christianity was not something new and taught the same elements of philosophy, only now, correctly understood:

- The One was in reality the God of Israel.

- The logos was the pre-existent form of Christ before his manifestation on earth.

Allegory & Metaphor

The methods by which ancient philosophers often described the universe, as well as traditional myths, was through allegory and metaphor. Allegory is a literary device that posits hidden meanings through symbolic figures, actions, images, and events, usually to provide a spiritual, or moral interpretation. Allegory offers a way in which a text can be open to more interpretations than traditionally understood. A metaphor is a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is substituted, for example: "The Universe is a sea of troubles."

The writer of John utilized allegory and metaphors to explicate the teachings of Jesus. He consistently applied the language of 'above' and 'below,' the spiritual and the mundane. Jesus, even on earth, existed on a 'higher plane' than everyone else. When he spoke to Nicodemus about being reborn, poor Nicodemus asked how it was possible to re-enter a mother's womb. His audience never understood because Jesus was 'from above,' and they were 'from below.' We see the distinction many times between the literal understanding of something and the 'higher' or more spiritual realm.

The 'above and below' is highlighted with the concepts of descent and ascent. Jesus descended to earth from the Father and predicted that he would ascend and return to the Father. The word for 'crucifixion' also meant "lifted up." John's Jesus never applied the literal meaning of crucifixion per se; he always referred to his upcoming death as "when I am lifted up" to the Father.

Some of the most memorable quotes from John's gospel stem from the "I am" metaphors throughout the text, seven in all:

- "I am the bread of life." (John 6:48)

- "I am the light of the world." (John 9:5)

- "I am the gate for the sheep." (John 10:7)

- "I am the good shepherd." (John 10:14)

- "I am the resurrection and the life." (John 11:25)

- "I am the vine, you are the branches." (John 15:5)

- "I am the way and the truth and the life." (John 14:6)

A bold declaration, the "I am" replicates the story of when Moses asked God his name and God answered, "I am who I am" (Exodus 3:14). This is John's rationale for Jesus as the only authoritative figure to preach the 'truth.' John's Jesus has authority because he is the only one who has seen the Father because he has come from the Father. John's line, "I am the way and the truth and the life" eventually became the Church's claim that salvation is only found through the Christian faith.

Highlights of the Gospel of John

John has some other unique elements that distinguish it from the Synoptics:

- John contains a denial of Jesus's baptism by John, emphasizing Jesus's independence from and superiority over the Baptist. He specifically has John the Baptist say that he must "decrease" so that Jesus can "increase." It is here that John first refers to Jesus as "the lamb of God" (John 1:29) Any astute reader would immediately realize that Jesus is going to be the sacrificial lamb who dies at Passover.

- John describes no self-reflective contemplation in the wilderness, no temptation by Satan in the wilderness, and no agony in Gethsemane. John's Jesus is so joined to the "Father" that he can never be tempted by worldly evil. There are no exorcisms. The Jews symbolize Satan and evil, and they are to be overcome by revelations of divine truth (see below).

- The form of John's teaching is radically different from the Synoptics. There is not a single parable in this gospel. Instead, we have long, philosophical discourses that point to the nature of god and the universe, the nature of Jesus, who he is, and how to discover universal truth.

- There are no debates and conflict dialogues concerning the Law of Moses. Unlike the Synoptics, John's Jesus is not in constant debate with the authorities over issues such as divorce, Sabbath, rituals, and tithing. John presented only one new commandment, that of love. This is the love of friends and companions (but only within the circle of believers) which becomes the way in which to distinguish the disciples from all others.

- The Gospel of John presents fewer miracles and signs. John does replicate several of the miracles of Jesus in the Synoptics, such as walking on water or multiplying the loaves and fishes. However, in John, the number is reduced to seven, and some are reframed in what scholars describe as 'signs miracles.' John reframes some of the Synoptic miracles to highlight the power of Jesus that is above and beyond any of the prophets or even Moses due to his unique status.

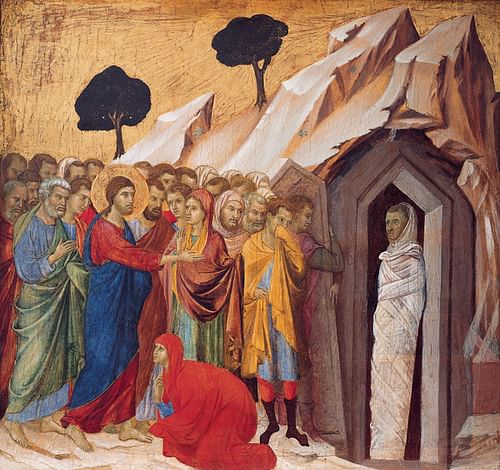

An example is the raising of Lazarus, only found in the fourth gospel. We read that Jesus deliberately stayed away even though word had reached him that Lazarus was ill. Showing up on the fourth day after he was dead, the tomb is already sealed. By tradition, the fourth day after death was when the body began to physically decay. While the Synoptics have stories of Jesus raising the dead, it was near the time of the actual death. In John, the significant point is that unlike other wonder-workers and itinerant holy men, this Jesus has the power to even raise someone after decomposition – a sign of the full and equal power of God in this individual.

John's Adjustments to the Trial and Crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth

In relation to the plot to kill Jesus, whereas Mark introduces the conflict dialogues at the beginning of the ministry, John has the Council meeting immediately after the raising of Lazarus event because "Here is this man performing many signs. If we let him go on like this, everyone will believe in him, and then the Romans will come and take away both our temple and our nation" (John 11:47-48). Caiaphas, the high priest speaks up and says, "You do not realize that it is better for you that one man die for the people than that the whole nation perish" (11:50). Many scholars consider John's version a more credible explanation for understanding the Jewish opposition to Jesus and his ministry.

In the Synoptics, Jesus and the disciples meet for the Passover Seder, the first night of the festival. In John, the last meal takes place on Wednesday evening, then he moves the actual crucifixion to the daylight hours right before Passover begins. This relates to his 'lamb' image. During the daylight hours before Passover began at sunset, the priests were busy slaughtering the lambs for everyone that evening. John has Jesus being crucified while the lambs are simultaneously being slaughtered in the Temple.

Unlike the Synoptic versions, John's Jesus is always in control. When the cohort with Judas came to arrest him and he identified himself, they "drew back and fell to the ground" (John 18:5). It was Jesus who permitted them to arrest him. In total control, John's Jesus experienced his crucifixion as his glorification. A divine being, Jesus cannot suffer in the human realm. The cross is the nexus of the descendent and the ascent, the meeting of the horizontal and the vertical. Unlike Mark's cry of desolation and despair ("My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" Mark 15:34), Jesus simply declared "It is finished [accomplished]" (John 19:30). He was sent to earth to bring light and truth to the world, and this is what has been "accomplished." Lacking the traditional elements of a passion, the crucifixion and death in John served as the means to get Jesus back home to the Father.

The Jews in John

The fourth gospel, in retrospect, is often described as the most antisemitic of the gospels. All of the gospels had to address the problem that, if Jesus was the messiah, why did not all the Jews believe in him when he was on earth? The Synoptics assigned the blame mainly on the Jewish leadership (the Pharisees, the scribes, the Sadducees). John collectively reduced the Jews to an oppositional, evil force throughout his gospel, utilizing the simple phrase "the Jews" throughout. This phrase appears 71 times in the gospel.

John's construction of the evil of the Jews is centered on the Jews being descendants of their father, Abraham. John's Jesus responded that God is their true father, but the Jews do not follow him:

If God were your Father, you would love me, for I have come here from God... You belong to your father, the devil, and you want to carry out your father's desires. He was a murderer from the beginning, not holding to the truth, for there is no truth in him. When he lies, he speaks his native language, for he is a liar and the father of lies. Yet because I tell the truth, you do not believe me! Can any of you prove me guilty of sin? If I am telling the truth, why don't you believe me? Whoever belongs to God hears what God says. The reason you do not hear is that you do not belong to God. (John 8:42-48)

John claimed that Jesus had no intention of including Jews in salvation, and at the same time salvation for Jews was never part of God's divine plan either. Hence, John's Jesus performed no exorcisms in this ministry. The role and presence of the Devil were manifest in the world through the Jews.

John's polemic against the Jews is not unique; polemic (then as now) was the standard way in which writers argued a point of view against another. Many scholars have attempted to recreate the historical context of John to try and understand his extreme view. One has a sense that John appears to demonstrate some bitterness against fellow Jews and Judaism.

A prevailing theory is that John and his group were kicked out of a synagogue. Or, at the very least, his group may have suffered harassment from fellow Jews while they remained part of the community. Tension most likely arose from John's unique claims: a pre-existent Jesus, present at creation (sharing this event with the God of Israel), and the "I am" metaphors that provided Jesus equal standing with God. This would later be canonized in the evolution of the Christian concept of the trinity at the First Council of Nicaea in 325 CE. In Judaism, however, worship was limited to the God of Israel.

The Kingdom of God

All of the gospels had to address the problem that although Jesus had preached the imminence of the kingdom of God during his lifetime, the kingdom had not materialized. The Synoptics claimed an early concept known as the parousia ("second appearance"). Christ, now in heaven, would shortly return and complete the predictions of the prophets for the final days. If we place John at or near the end of the 1st century CE, 70 years had passed since the ministry.

John 14 has a discourse from Jesus where he stated that "My Father’s house has many rooms" (14:2) and that he was going there to prepare a place for the disciples. John's Jesus is not going to physically return. He promised the disciples that help would be sent in the form of the paraclete (Greek for "advocate"), which was John's concept of the spirit of God. This presence of the spirit in the community provides scholars with a concept known as 'realized eschatology.'

Realized eschatology is a construct that attempts to interpret John's language as what appears to be an existential conversion of the inner man ("the kingdom is within you”). In other words, as time passed and the kingdom did not arrive, 'kingdom' became a metaphor for the way in which believers could absorb the theological elements into both their conceptual thinking as well as their daily lives. The teaching in John is often described as uniquely concerned with individual salvation and less as a communal matter.

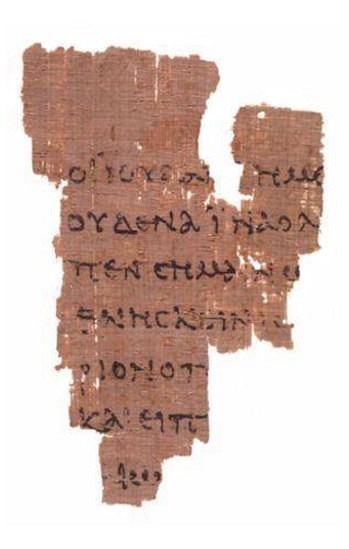

Our oldest fragment of extant manuscript of a gospel, Papyrus 52 (located in the Egyptian collection of the John Rylands Library in Manchester, England) is from John's gospel:

"I am a king. In fact, the reason I was born and came into the world is to testify to the truth. Everyone on the side of truth listens to me." "What is truth?" retorted Pilate. With this he went out again to the Jews gathered there and said, "I find no basis for a charge against him." (John 18:37-39)

John's gospel remains popular in modern Christianity because of those powerful quotes. Elements of John are summarized as simple, shorthand ways in which to declare the 'truth' of Christianity: "For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life" (John 3:16).