In ancient Greece, dance had a significant presence in everyday life. The Greeks not only danced on many different occasions, but they also recognized several non-performative activities such as ball-playing or rhythmic physical exercise as dance. In fact, dancing to the ancient Greeks seemed like a natural response of the body, mind, and soul to music. They would dance spontaneously at weddings or drinking parties (symposia), or perform pre-arranged choreographies as exemplified by the chorus' dances in the ancient Greek theatre. Greek dances could be performed individually or in a group. They could tell a story, showcase martial and athletic skills, entertain guests, or shape processions and other key parts of religious rituals.

Whilst dance is largely defined in ancient Greek literature as an element of the mousike (the umbrella term which covers all categories of the performing arts: making music, dancing, singing, and recitation), there is a wide range of evidence that suggests dancing was practiced as an independent skill. Dance-training (gymnopaidai) was a foundation subject in school, and pictures of boys and girls practicing dance under the supervision of male and female tutors appear in vase painting. Classical writers such as Plato, Lucian, and Athenaeus recommended dancing as an essential part of the development of good citizens, men and women, thanks to its constructive effects on the body and mind. As in many ancient cultures, dancing played a fundamental role in ancient Greek society for thousands of years.

Origins

The origins of the Greek dance date back to the 2nd millennium BCE. Tradition has it that Crete, home of the Minoan civilization, is the birthplace of Greek dance. Minoan art and culture had a great impact on the Mycenaean civilization and the Cycladic people, and these three together cradled what is known today as the classical Greek, or Hellenic, culture. Therefore, it is very likely that the Greek dance forms effectively evolved from their origins in Minoan Crete. The Greek tragedy playwright Sophocles (c. 496 - c. 406 BCE), in his Ajax, calls Pan the dancemaker of the gods who had invented dances based on the dance steps practiced in Knossos. Athenaeus, too, highlights Crete as the birthplace of several kinds of dance, including the pyrrhic or war-dance and the sikinnis or the satyr dance. Seals and gold rings decorated with engraved figures of dancing women were found in Isopata, near Knossos, and Hagia Triada, near Phaistos, from c. 1500 BCE. At the eastern end of Crete, Palaikastro gives us clay figurines of several female dancers, who also appear in the wall-paintings of the Late Minoan palace at Knossos.

The Cretan painted and sculpted figures of dancing women are often identified as goddesses or priestesses, which suggests a fundamental relationship between dancing and religious beliefs common among most early communities and ancient civilizations, including ancient Greece. Lucian, to whom we owe the only surviving complete text about the ancient (Greco-Roman) dance, believed that dance is a cosmic creation because the stars and planets in their harmonious travels dance around the universe. In Greek mythology, Urania, the Muse of astronomy, had some presidency over dance as well, taking over the theoretical side of the art of dancing, whose main patroness was her sister Terpsichore, the “dance delight.” The primordial significance of dance in ancient Greece is underlined by archaeology. The earliest inscription written in the Greek alphabet found so far, the Dipylon Inscription, on a terracotta wine-jug, labels it as a prize to “whoever of these dancers now plays [dances] most delicately.”

Dance Forms

Greek dance forms can be categorized, overall, into individual and collective or group performances. The individual format is further divided into solo performances (of professional entertainers) and freestyle dancing for leisure (similar to modern party dancing). Solo performances are greatly associated with acrobatic and/or spectacular displays. Xenophon (430 - c. 354 BCE) in his Anabasis admires some young escorts of the Greek mercenary who took turns to entertain the Greeks and the Paphlagonians celebrating their agreement of peace. One dancer grabbed a light shield and recreated a scene of combat against two imaginary warriors, then he danced a Persian dance which, again, consisted of martial movements. Then a girl, dressed as a warrior, dazzled the audience with her brilliant performance of the pyrrhic dance, the dance of fire, the most popular war-dance in the Greek world.

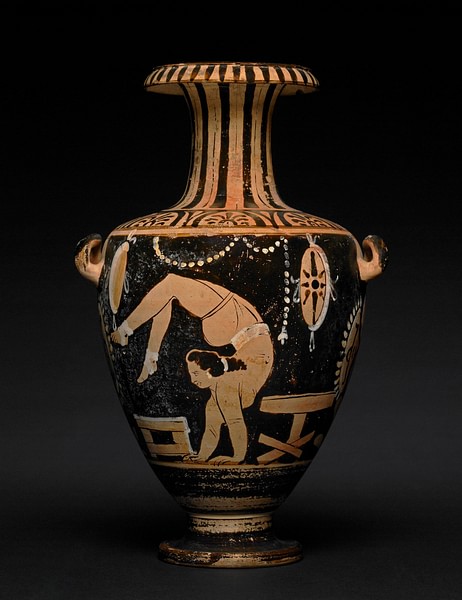

Another venue for solo performances was the symposium, where professional troupes could be hired to provide musical entertainment. Music was the main substance of hēdonē (pleasure) and could involve a few orchestridēs (dancing girls) dancing to the musical accompaniment of professional female musicians, aulētrides (aulos girls) and psaltriai (harp girls). Sometimes the dancing girls also contributed to the music-making and kept the beat with a pair of krotala (clappers). If the host could afford a complete troupe, then the entertainment also included a kind of variety show with different numbers of graceful dance improvisations and amazing acrobatic and musical actions.

Symposia are also our main source of knowledge about the spontaneous, freestyle dancing of the Greek people. Revelry was, in fact, a common form of individual improvisation with loose body shaking in a group of fellow-drinkers. It was often the great finale of a typical symposium when the guests rushed out singing and leaping and jumping up and down all the way home, giving out shouts of praise to Dionysos, the god of wine, in their satyric komos dance or “dance of frenzied drunkards”.

The second category of Greek dance forms is the group performance. This involves a series of synchronized, similar, and often pre-planned movements performed by a group, whose members could consist of semi-professionals (as in theatrical choruses) or lay attendants (of religious rituals, weddings, and funerals), unisex or all-male and/or all-female. It is often stated that dancing in antiquity was a collective activity, and the Greek dance is largely summed up as a group dance. Homer (c. 750 BCE), the earliest of many ancient writers who touch upon dancing, in his Iliad describes the Achilles' shield decorated with three groups of dancing boys and girls. In material culture, named Greek dancers first appear on the Francois Vase, c. 575 BCE, a large krater for mixing wine with water. The topmost frieze of this vase, under the brim, shows a group of 14 youths and maidens who hold hands and step in a line to celebrate their redemption by Theseus, the Athenian prince and hero, from the Cretan labyrinth.

Plutarch, Pollux, and Lucian, among others, linked this dance with the geranos, a popular chain dance of a fast pace. In fact, linear is only one, although perhaps the most frequent, format of the Greek group dance. The other two formats are circular and zigzag. Linear dances are largely tied with both religious rites such as processions in public festivals and daily occasions such as weddings and funerals. Circular formats, too, were often part of a ritual when the line dancers began to dance around the altar of a deity. In dances like the geranos that had connections with the labyrinth and the thread given to Theseus by Ariadne to find his way back, the dancers could imitate the twists and turns of these two elements.

The linear and circular dance forms were often used in the most famous dance of ancient Greece, the theatrical dance of the chorus. The original form of this dance, the dithyramb, is largely associated with Dionysos. It was the most enduring form of collective performance which lasted from the 7th century BCE until Late Antiquity. The Great Dionysia, known as the birthplace of Greek drama, was developed when the 6th-century BCE lyric poet Lasus of Hermione introduced this form of choral dancing and singing to Athens. The chorus in the Greek theatre performed a series of choreographed movements in parabasis, the choral deliverance of the playwright's message to the audience. The chorus was led by a choregos, the chorus-leader. The pace and rhythm of the dances could vary according to the poetic measures of the play, and there was a specific type of dance for each of the dramatic genres. The chorus performed the emmeleia in tragedies, the kordax in Greek comedy, and the sikinnis in a satyr-play.

Dancing Figures

Dancing figures, both mythical and historical, have many representations in ancient Greek literature. Odysseus admires Nausicaa's beauty and charm revealed through her delightful dancing. Hermes falls in love with Philomela when he sees her dancing in honour of Artemis. Hippocleides, an Athenian nobleman chosen among the most eminent suitors to marry Agariste, the princess of Sicyon in the early 6th century BCE, “danced away” his marriage by performing an inappropriate amalgamation of acrobatic and komos dance in his blind drunkenness.

The most (in)famous dancing characters, however, are the companions of no other deity than Dionysos. His male retinue consists of the satyrs, half-men and half-goat, known for their incurably merry and mischievous characters. More often than not, the satyrs are dancing and chasing young women, particularly the maenads, female worshippers of Dionysos. The maenads, meaning “frantic women,” wore fawn-skins and carried thyrsos, a long stick of fennel or pine. Their ecstatic dancing often culminated in violence and extraordinary behaviours such as handling snakes and dismembering animals. The Greek tragedian Euripides (c. 484-407 BCE) in The Bacchae, another name for the maenads after Bacchus, tells the story of the Theban women who, led by Queen Mother Agave in their madness cast by Dionysos himself, kill Pentheus, the king.

These mythical dancers were imitated by mortals as well. The Pronomos Vase, a large and elaborately decorated volute-krater from c. 400 BCE, displays a behind-the-scenes preparation of male actors dressed as the satyrs, crowding around Demetrios, the writer of the satyr play they are about to perform. On the other side of this vase, Dionysos and his dancer spouse, Ariadne, the Cretan princess, look down on Pronomos, the pipe-player. Women on many occasions acted as the maenads. These could be part of a festival or a woman-only ritual. In the annual festival of the Agrionia, for example, once three groups of dancing women hastened away to the mountains, wandering around all night in their collective ecstasy to rise above their earthly existence and join their god, Dionysos.

While it is difficult to trace the modern Greek dance all the way back to antiquity, the ancient Greek dance forms and movements are still to be found in various Greek communities today. Ancient Greek dance, together with its associated stories and figures, has inspired, and keep inspiring, writers, poets, painters, dancers, stage performers, and many others throughout the ages and across many cultures around the world.