In ancient Greek medicine illness was initially regarded as a divine punishment and healing as, quite literally, a gift from the gods. However, by the 5th century BCE, there were attempts to identify the material causes for illnesses rather than spiritual ones and this led to a move away from superstition towards scientific enquiry, although, in reality, the two would never be wholly separated. Greek medical practitioners, then, began to take a greater interest in the body itself and to explore the connection between cause and effect, the relation of symptoms to the illness itself and the success or failure of various treatments.

Greek Views on Health

Greek medicine was not a uniform body of knowledge and practice but rather a diverse collection of methods and beliefs which depended on such general factors as geography and time period and more specific factors such as local traditions and a patient's gender and social class. Nevertheless, common threads running through Greek medical thought included a preoccupation with the positive and negative effects of diet and a belief that the patient could actually do something about their complaint, in contrast to a more fatalistic and spiritual mindset of earlier times.

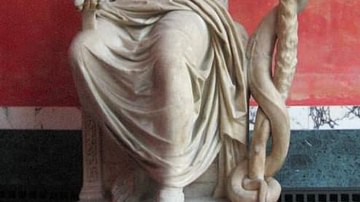

However, the distinction between the spiritual and physical worlds are often blurred in Greek medicine, for example, the god Asclepius was considered a dispenser of healing but also a highly skilled practical doctor. The god was called upon by patients at his various sanctuaries (notably Epidaurus) to give the patient advice through dreams which the site practitioners could then act upon. Grateful patients at the site often left monuments which reveal some of the problems that needed to be treated, they include blindness, worms, lameness, snakebites and aphasia. As Epidaurus illustrates, there could, then, be both a divine and a physical cause or remedy for illnesses.

Lifestyle and such factors as heat, cold and trauma were discovered to be important factors in people's health and they could alleviate or worsen the symptoms of an illness or the illness itself. It was also recognised that a person's physical constitution could also affect the severity of, or susceptibility to, an illness. There was also a growing belief that a better understanding of the causes of an illness' symptoms could help in the fight against the illness itself. With a greater knowledge of the body there also came a belief that the balance of the various fluids (humours) within it could be a factor in causing illness. So too, the observation of symptoms and their variations became a preoccupation of the Greek doctor.

Greek Medical Sources

Textual sources on Greek medical practice begin with scenes from Homer's Iliad where the wounded in the Trojan War are treated, for example, Patroclus cleaning Eurypylus' wound with warm water. Medical matters and doctors are also frequently mentioned in other types of Greek literature such as comedy plays but the most detailed sources come from around 60 treatises often attributed to Hippocrates (5th to 4th century BCE), the most famous doctor of all. However, none of these medical treatises can be confidently ascribed to Hippocrates and next to nothing is known about him for certain.

The Hippocratic texts deal with all manner of medical topics but can be grouped into the main categories of diagnosis, biology, treatment and general advice for doctors. Another source is the fragmentary texts from the Greek natural philosophy corpus dating from the 6th to 5th century BCE. Philosophers in general, seeing the benefits of good health on the mind and soul, were frequently concerned either directly or indirectly with the human body and medicine. These thinkers include Plato (especially in Timaeus), Empedocles of Acragas, Philistion of Locri and Anaxagoras.

Doctors & Practitioners

As there were no professional qualifications for medical practitioners then anyone could set themselves up as a doctor and travel around looking for patients on whom to practise what was known as the tekhnē of medicine (or art, albeit a mysterious one). The Spartans did, though, have specific personnel responsible for medical care in their professional army. Also, practitioners do seem to have generally enjoyed a high regard despite the lack of a recognised professional body to supervise and train would-be doctors and the odd mad doctor that crops up in Greek Comedy. As Homer states in the Iliad (11.514), 'a doctor is worth many other men'. Not only doctors gave medical advice and treatment but other groups who could utilise their practical experience such as midwives and gym trainers.

The famous Hippocratic Oath was probably reserved for a select group of doctors and it was actually a religious document ensuring a doctor operated within and for community values. With the Oath, the practitioner swore by Apollo, Hygieia and Panacea to respect their teacher and not to administer poison, abuse patients in any way, use a knife or break the confidentiality between patient and doctor.

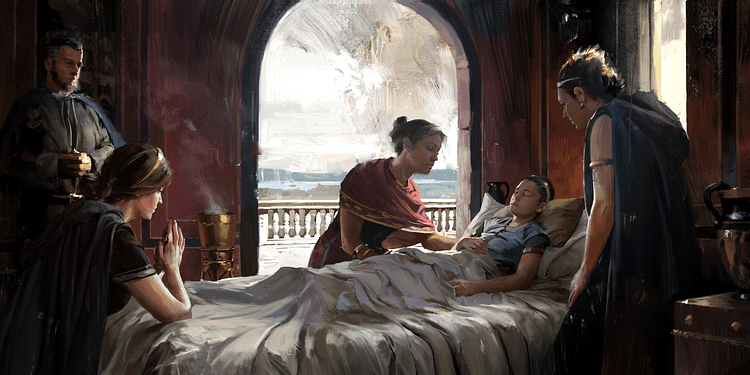

Famous medical practitioners included the 4th century BCE figures of Diocles of Carystus (who had a head bandage and spoon instrument for removing arrowheads named after him), Praxagoras of Cos (noted for his 'discovery' of the pulse and being the first to distinguish veins from arteries), and the Athenians Mnesitheus and Dieuches. These experts in their field could examine a patient's face and make a diagnosis helped by information such as the patient's diet, bowel movements, appetite and sleeping habits. Treatments often utilised natural plants such as herbs and roots but could also include the use of amulets and charms. Surgery was generally avoided as it was considered too risky but minor operations may have been carried out, especially on soldiers wounded in battle.

Medical Treatments: War

Wounded soldiers were actually one of the best ways for a doctor to learn his trade and widen his knowledge of the human body and its internal workings. There was probably also less risk of the soldier causing problems if things went wrong, which could happen with private patients. Aside from the health problems which may also have affected civilians such as malnutrition, dehydration, hypothermia, fever and typhoid, those doctors treating soldiers had to deal with wounds made by swords, spears, javelins, arrows and projectiles from slings. Medical practitioners knew the importance of removing foreign bodies such as arrowheads from the wound and the necessity to properly clean the wound (which is why arrowheads became barbed to be more difficult to remove and therefore more lethal). Greek doctors knew that it was important to stop excessive blood loss as soon as possible in order to prevent haemorrhage (although they also thought blood-letting could be beneficial too). Surgery may also have included the use of opium as an anaesthetic, although the many references in literature to patients being held down during surgery would suggest that the use of anaesthetic was rare.

Post-operation, wounds were closed using stitches of flax or linen thread and the wound dressed with linen bandages or sponges, sometimes soaked in water, wine, oil or vinegar. Leaves could also be used for the same purpose and wounds may also have been sealed using egg-white or honey. Post-operation treatment was also considered - the importance of diet, for example, or the use of plants with anti-inflammatory properties such as celery.

Discoveries & Developments

Over time doctors came to acquire a basic knowledge of human anatomy, assisted, no doubt, by the observation of grievously wounded soldiers and, from the 4th century BCE, animal dissection. However, some claimed this was useless as they believed the inner body changed on contact with air and light and still others, as today, protested that using animals for such purposes was cruel. Human dissection would have to wait until Hellenistic times when such discoveries as the full nervous system were discovered. Nevertheless, there was an increasing urge to discover what made a healthy body function well rather than what had made an unhealthy one break down. The lack of practical knowledge, though, did result in some fundamental errors such as Aristotle's belief that the heart and not the brain controlled the body and the idea proposed in the treatise On Ancient Medicine (5th century BCE) that physical pain arises from the body's inability to assimilate certain foods.