Ancient Greek philosophy is a system of thought, first developed in the 6th century BCE, which was informed by a focus on the First Cause of observable phenomena. Prior to the development of this system by Thales of Miletus (l. c. 585 BCE), the world was understood by the ancient Greeks as having been created by the gods.

Without denying the existence of the gods, Thales suggested that the First Cause of existence was water. This suggestion brought no backlash of charges of impiety because water, as a life-giving agency which encircled the earth, was already associated with the gods by Greek religion. Thales' followers, Anaximander (l. c. 610 - c. 546 BCE) and Anaximenes (l. c. 546 BCE) continued his studies and examinations of the nature of reality but suggested different elements as the First Cause.

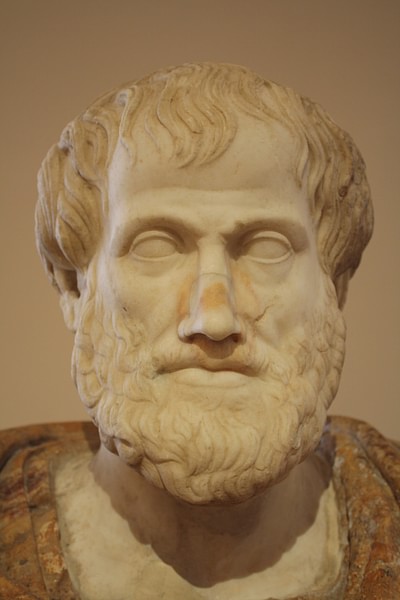

These three men initiated the path of inquiry known as ancient Greek philosophy, which was developed by the so-called Pre-Socratic Philosophers, defined as those who engaged in philosophic speculation and the development of different schools of thought from Thales' first efforts up to the time of Socrates of Athens (l. 470/469-399 BCE), who, according to his most famous pupil Plato (l. 424/423-348/347 BCE), enlarged the scope of philosophy to address not only the First Cause but also the individual's moral and ethical obligation to self-improvement for its own sake and the good of the greater community. Plato's work inspired his student Aristotle of Stagira (l. 384-322 BCE) to establish his own school with his own vision based on but significantly different from Plato's own.

Aristotle would go on to become the tutor of Alexander the Great (l. 356-323 BCE) who, through his conquest of Persia, spread the concepts of Greek philosophy throughout the East from the regions of modern-day Turkey up through Iraq and Iran, across through Russia, down to India, and back toward Egypt where it would influence the development of the school of thought known as Neo-Platonism as formulated by the philosopher Plotinus (l. c. 202-274 CE) whose vision, developed from Plato's, of the Divine Mind and a higher reality which informs the observable world would influence that of Paul the Apostle (l. c. 5-64 CE) in his understanding and interpretation of the mission and meaning of Jesus Christ, laying the foundation for Christianity's development.

The works of Aristotle, which would come to inform Christianity as much as Plato's, would also be instrumental in the formulation of Islamic thought after Islam was established in the 7th century CE as well as the theological concepts of Judaism. In the present day, Greek philosophy is the underlying form of belief systems, cultural values, and legal codes all around the world as it has largely contributed to their development.

Ancient Greek Religion

Ancient Greek religion maintained that the observable world and everything in it was created by the immortal gods who took a personal interest in the lives of human beings to guide and protect them; in return, humanity thanked their benefactors through praise and worship, which eventually became institutionalized through temples, clergy, and ritual. The Greek writer Hesiod (l. 8th century BCE) codified this belief system in his work Theogony and the Greek poet Homer (l. 8th century BCE) would illustrate it fully in his Iliad and Odyssey.

Humans were created, as well as all plants and animals, by the gods of Mount Olympus who regulated the seasons and were understood as the First Cause of existence. Stories, now known as Greek mythology, developed to explain various aspects of life and how the gods should be understood and worshipped and therefore, in this cultural climate, there was no intellectual or spiritual motivation to search for a First Cause because that was already well established and defined.

Origin of Greek Philosophy

Thales of Miletus was a cultural aberration in that, instead of accepting his culture's theological definition of a First Cause, he sought his own in a reasoned inquiry into the natural world, working from what he could observe backwards to what had caused it to come into being. The question later philosophers, historians, and social scientists have posed, however, is how he came to begin his inquiry. Modern-day scholars are by no means in agreement on an answer to this question and, generally speaking, maintain two views:

- Thales is an original thinker who developed a novel way of inquiry.

- Thales developed his philosophy from Babylonian and Egyptian sources.

Egypt had a long-established trade relationship with the cities of Mesopotamia, including Babylon of course, by Thales' time, and both the Mesopotamians and Egyptians believed that water was the underlying element of existence. The Babylonian creation story (from the Enuma Elish, c. 1750 BCE in written form) tells the story of the goddess Tiamat (meaning sea) and her defeat by the god Marduk who then creates the world from her remains. The Egyptian creation story also features water as the primordial element of chaos from which earth arises, the god Atum brings under his control, and order is established, eventually resulting in the creation of the other gods, animals, and human beings.

It has long been established that ancient Greek philosophy begins in the Greek colonies of Ionia along the coast of Asia Minor as the first three Pre-Socratic philosophers all came from Ionian Miletus and the Milesian School is the first Greek philosophical school of thought. The standard explanation as to how Thales first conceived of his philosophy has been the first one cited above. The second theory, however, actually makes more sense in that no school of thought develops in a vacuum and there is nothing in the Greek culture of the 6th century BCE to suggest that intellectual inquiry into the cause of observable phenomena was valued or encouraged.

Scholar G. G. M. James notes that many later philosophers, from Pythagoras to Plato, are said to have studied in Egypt and, in part, to have developed their philosophies there. He suggests that Thales might also have studied in Egypt and established this practice as a tradition others would follow. While this certainly may be the case, there is no documentation to definitively support it while it is known that Thales did study in Babylon. He would have certainly been exposed to Mesopotamian, as well as Egyptian, philosophy in his studies there, and this was most likely the source of his inspiration.

Pre-Socratic Philosophers

However he may have first developed his vision of a reasoned, empirical inquiry into the nature of reality, Thales began an intellectual movement which inspired others to do the same. These philosophers are known as Pre-Socratic because they pre-date Socrates, and following the formulation of scholar Forrest E. Baird, the major Pre-Socratic philosophers were:

- Thales of Miletus – l. c. 585 BCE

- Anaximander – l. c. 610 - c. 546 BCE

- Anaximenes – l. c. 546 BCE

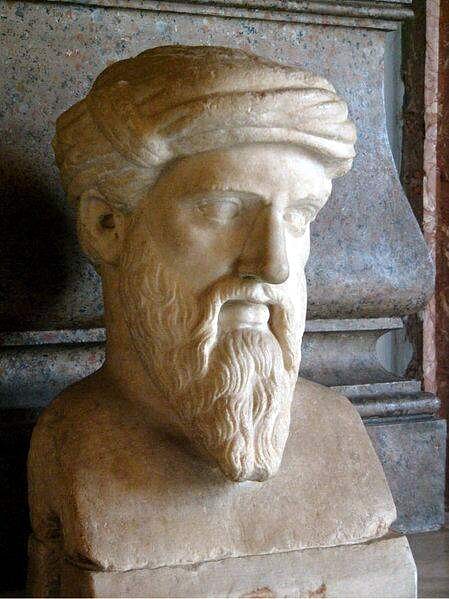

- Pythagoras – l. c. 571 - c. 497 BCE

- Xenophanes of Colophon – l. c. 570 - c. 478 BCE

- Heraclitus – l. c. 500 BCE

- Parmenides of Elea – l. c. 485 BCE

- Zeno of Elea – l. c. 465 BCE

- Empedocles – l. c. 484-424 BCE

- Anaxagoras – l. c. 500 - c. 428 BCE

- Democritus – l. c. 460 - c. 370 BCE

- Leucippus – l. c. 5th century BCE

- Protagoras – l. c. 485 - c. 415 BCE

- Gorgias – l. c. 427 BCE

- Critias l. c. 460-403 BCE

The first three were focused on the First Cause for existence. Thales claimed it was water, but Anaximander rejected this in favor of the higher concept of the apeiron – “the unlimited, boundless, infinite, or indefinite” (Baird, 10) – which was an eternal creative force. Anaximenes claimed air as the First Cause for the same reason Thales chose water: he felt it was the element which was the most basic component of all others in varied forms.

The definition of a First Cause was rejected by Pythagoras who claimed number as Truth. Numbers have no beginning or end and neither does the world or a person's soul. One's immortal soul goes through many incarnations, acquiring wisdom, and although Pythagoras suggests it finally joins with a higher soul (God), how he defined that oversoul is unclear. Xenophanes answers this with his claim that there is only one God who is the First Cause and also governor of the world. He rejected the anthropomorphic vision of the Olympian Gods for a monotheistic vision of God as Pure Spirit.

His younger contemporary, Heraclitus, rejected this view and replaced “God” with “Change”. To Heraclitus, life was flux – change was the very definition of “life” – and all things came into being and passed on owing simply to the nature of existence.

Parmenides combined these two views in his Eleatic School of thought which taught Monism, the belief that all of observable reality is of one single substance, uncreated, and indestructible. Parmenides' thought was developed by his pupil Zeno of Elea, who created a series of logical paradoxes proving that plurality was an illusion of the senses and reality was actually uniform.

Empedocles combined his predecessor's philosophies with his own, claiming that the four elements were brought into being by strife by natural forces clashing with each other but were sustained by love, which he defined as a creative and regenerating force. Anaxagoras took this idea and developed his concept of like-and-not-like and “seeds”. Nothing can come from what it is not like and everything is comprised of particles (“seeds”) which constitute that particular thing.

His "seed” theory would influence the development of the concept of the atom by Leucippus and his student Democritus, who, in looking into the basic "seed" of all things, claimed that the entire universe is made up of “un-cutables” known as atamos. The atomic theory inspired Leucippus in his theory of fatalism in that, just as atoms constituted the observable world, so their dissolution and reformation directed a person's fate.

The works of these philosophers (and the many others not mentioned here) encouraged the development of the profession of the Sophist – highly educated intellectuals who, for a price, would instruct the upper-class male youth of Greece in these various philosophies as part of their goal in teaching art of skill in persuasion for winning arguments. Lawsuits were common in ancient Greece, especially at Athens, and the skills the Sophists offered were highly valued. Just as the earlier philosophers argued against what was accepted as “common knowledge”, so the Sophists taught the means by which one could “make the worse appear the better cause” in any argument.

Among the most famous of these teachers were Protagoras, Gorgias, and Critias. Protagoras is best known for his claim that “man is the measure of all things”, everything is relative to individual experience and interpretation. Gorgias taught that what people call “knowledge” is only opinion and actual knowledge is incomprehensible. Critias, an early follower of Socrates, is best known for his argument that religion was created by strong and clever men to control the weak and gullible.

Socrates, Plato, & the Socratic Schools

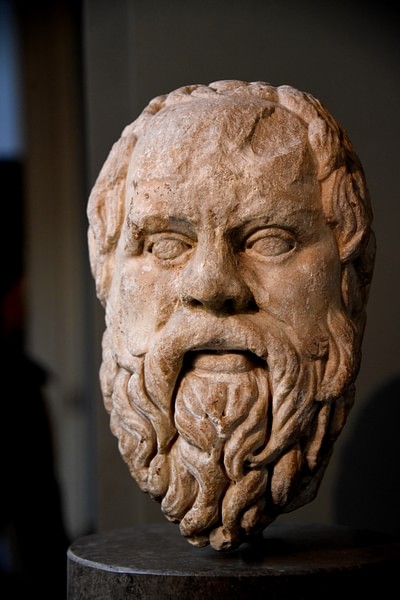

Socrates is considered by some to have been a kind of Sophist, but one who taught freely without expectation of reward. Socrates himself wrote nothing, and all that is known of his philosophy comes from his two students Plato and Xenophon (l. 430 - c. 354 BCE) and the forms his philosophy took in the later philosophic schools founded by his other followers such as Antisthenes of Athens (l. c. 445-365 BCE), Aristippus of Cyrene (l. c. 435-356 BCE), and others.

Socrates' focus was on the improvement of individual character, which he defined as the “soul”, in order to live a virtuous life. His central vision is summed up in the claim attributed to him by Plato that “an unexamined life is not worth living” (Apology 38b) and that one should not, therefore, simply repeat what one has learned from others but, instead, examine what one believes – and how one's beliefs inform one's behavior – in order to know one's self truly and behave justly. His central teachings are given in four of Plato's dialogues, usually published under the title The Last Days of Socrates – Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, and Phaedo – which recount his indictment by the Athenians on charges of impiety and corrupting the youth, his trial, time in prison, and execution.

Plato's other dialogues – almost all of which feature Socrates as the central character – may or may not reflect Socrates' actual thought. Even contemporaries of Plato claimed that the “Socrates” who appeared in his dialogues bore no resemblance to the teacher they had known. Antisthenes founded the Cynic school, which focused on simplicity in living – on behavior as character – and denial of any luxury as its basic tenet, while Aristippus founded the Cyrenaic school of hedonism in which luxury and pleasure were held to be the highest goals one could aspire to. Both of these men were students of Socrates, just as Plato was, but their philosophies have little or nothing in common with his.

Whatever the historical Socrates may have taught, the philosophy Plato attributes to him is based on the concept of an eternal realm of Truth (the Realm of Forms) of which observable reality is only a reflection. The concepts of Truth, Goodness, Beauty, and others exist in this realm, and what people refer to as true, good, or beautiful are only attempts at definition, not the things themselves. Plato claimed that people's understanding was darkened and limited by acceptance of the “true lie” (also known as the Lie in the Soul), which caused them to believe wrongly about the most important aspects of human life. In order to free one's self from this lie, one had to recognize the existence of the higher realm and align one's understanding with it through the pursuit of wisdom.

Aristotle & Plotinus

It could be that Plato purposefully attributed his own philosophical ideas to Socrates to avoid the same fate as his teacher. Socrates was convicted of impiety and executed in 399 BCE, scattering his followers. Plato himself went to Egypt and visited a number of other places before returning to Athens to set up his Academy and begin writing his dialogues. Among his most famous students at the new school was Aristotle, son of Nichomachus from Stagira near the Macedonian border.

Aristotle rejected Plato's Theory of Forms and focused on a teleological approach to philosophical inquiry in which first causes are arrived at by examining final states. One would not, Aristotle claims, try to understand how a tree grows from a seed by contemplating its “treeness” but by looking at the tree itself, observing how it grows, what constitutes a seed, what soil seems best for its growth. In the same way, one cannot understand humanity by considering what a human “should” be but by recognizing what one is and how an individual human could improve.

Aristotle believed that the entire purpose of human life was happiness. People were unhappy because they confused material wealth or position or relationships – all of which were impermanent – with lasting, internal satisfaction, which was cultivated by developing arete (“personal excellence”), which allowed one to experience eudaimonia (“to be possessed of a good spirit”). Having attained eudaimonia, one could not lose it, and one could then see clearly to help others toward the same state. He believed that the First Cause was a force he defined as the Prime Mover – that set everything in motion – but that, afterwards, things which were in motion stayed in motion. Concerns about a First Cause were not as important to him as an understanding of how the observable world worked and how best to live in it.

Aristotle became the tutor of Alexander the Great who would then spread his philosophy, as well as that of his predecessors throughout the world of the Near East and as far as India while, at the same time, Aristotle set up his own school, the Lyceum, in Athens and taught students there. He investigated virtually every area and discipline of human knowledge throughout the rest of his life and was known simply as The Master by later writers.

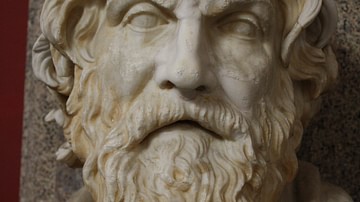

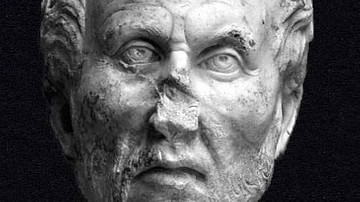

Not every one of these later thinkers ascribed to his philosophy completely, however, and among these was Plotinus who took the best of Plato's idealism and Aristotle's teleological approach and combined them in the philosophy known as Neo-Platonism, which also contained elements of Indian, Egyptian, and Persian mysticism. In this philosophy, there is an Ultimate Truth - so great that it cannot be comprehended by the human mind - which was never created, can never be destroyed, and cannot even be named; Plotinus called this the nous which translates as Divine Mind.

The purpose of life is to awaken the soul to awareness of the Divine Mind and then live accordingly. That which people call “evil” is caused by attachment to the impermanent things of this world and the illusions which people think make them happy; true “good” is recognition of the impermanent and ultimately unsatisfying nature of the material world and a focus on the Divine Mind from which all goodness in life comes.

Conclusion

Plotinus answers Thales' question regarding the First Cause with the answer he was trying to move away from, the divine. Like the gods of ancient Greece, the nous was a belief that could not be proven; one only knew of it by observable phenomena interpreted according to one's belief. Plotinus' insistence on the reality of the nous was encouraged by his dissatisfaction with any other answer. In order for anything in the world to be true, there has to be a source for Truth, and if everything is relative to the individual, as Protagoras claimed, then there is no such thing as Truth, there is only opinion. Plotinus, like Plato, rejected Protagoras' view and established the Divine Mind as the source not only of truth but of all life and consciousness itself.

His Neo-Platonic thought would influence Saint Paul in his development of the Christian vision. The Christian god was understood by Paul in very much the same terms as Plotinus' nous, only as an individual deity with a distinct character rather than a nebulous Divine Mind. Aristotle's works, which had been translated and were better known in the Near East, influenced the development of Islamic theology while Jewish scholars drew on Plato, Aristotle, and Plotinus in the formation of their own.

Ancient Greek philosophy also came to inform cultural values around the world, not only initially through the conquests of Alexander the Great but through its dissemination by later writers. Legal codes and secular concepts of morality up to the present day are derived from the philosophy of the Greeks, and even those who have never read the works of a single ancient Greek philosopher have been influenced by them to greater or lesser degrees. From Thales' initial inquiry into first causes to the intricate metaphysics of Plotinus, ancient Greek philosophy found an admiring audience searching for the same answers to the questions it posed and, as it spread, provided the cultural foundation for Western Civilization.