Greek tragedy was a popular and influential form of drama performed in theatres across ancient Greece from the late 6th century BCE. The most famous playwrights of the genre were Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides and many of their works were still performed centuries after their initial premiere. Greek tragedy led to Greek comedy and, together, these genres formed the foundation upon which all modern theatre is based.

The Origins of Tragedy

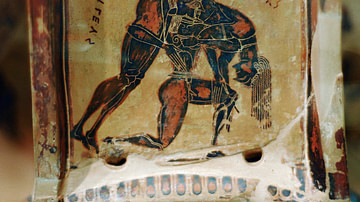

The exact origins of tragedy (tragōida) are debated amongst scholars. Some have linked the rise of the genre, which began in Athens, to the earlier art form, the lyrical performance of epic poetry. Others suggest a strong link with the rituals performed in the worship of Dionysos such as the sacrifice of goats - a song ritual called trag-ōdia - and the wearing of masks. Indeed, Dionysos became known as the god of theatre and perhaps there is another connection - the drinking rites which resulted in the worshipper losing full control of their emotions and in effect becoming another person, much as actors (hupokritai) hope to do when performing. The music and dance of Dionysiac ritual was most evident in the role of the chorus and the music provided by an aulos player, but rhythmic elements were also preserved in the use of first, trochaic tetrameter and then iambic trimeter in the delivery of the spoken words.

A Tragedy Play

Performed in an open-air theatre (theatron) such as that of Dionysos in Athens and seemingly open to all of the male populace (the presence of women is contested), the plot of a tragedy was almost always inspired by episodes from Greek mythology, which we must remember were often a part of Greek religion. As a consequence of this serious subject matter, which often dealt with moral right and wrongs, no violence was permitted on the stage and the death of a character had to be heard from offstage and not seen. Similarly, at least in the early stages of the genre, the poet could not make comments or political statements through the play, and the more direct treatment of contemporary events had to wait for the arrival of the less austere and conventional genre, Greek comedy.

The early tragedies had only one actor who would perform in costume and wear a mask, allowing him the presumption of impersonating a god. Here we can see perhaps the link to earlier religious ritual where proceedings might have been carried out by a priest. Later, the actor would often speak to the leader of the chorus, a group of up to 15 actors who sang and danced but did not speak. This innovation is credited to Thespis in c. 520 BCE. The actor also changed costumes during the performance (using a small tent behind the stage, the skēne, which would later develop into a monumental façade) and so break the play into distinct episodes. Phrynichos is credited with the idea of splitting the chorus into different groups to represent men, women, elders, etc. (although all actors on the stage were in fact male). Eventually, three actors were permitted on stage - a limitation which allowed for equality between poets in competition. However, a play could have as many non-speaking performers as required, so, no doubt, plays with greater financial backing could put on a more spectacular production with finer costumes and sets. Finally, Agathon is credited with adding musical interludes unconnected with the story itself.

Tragedy in Competition

The most famous competition for the performance of tragedy was as part of the spring festival of Dionysos Eleuthereus or the City Dionysia in Athens, but there were many others. Those plays which sought to be performed in the competitions of a religious festival (agōn) had to go through an audition process judged by the archon. Only those deemed worthy of the festival would be given the financial backing necessary to procure a costly chorus and rehearsal time. The archon would also nominate the three chorēgoi, the citizens who would each be expected to fund the chorus for one of the chosen plays (the state paid the poet and lead actors). The plays of the three selected poets were judged on the day by a panel and the prize for the winner of such competitions, besides honour and prestige, was often a bronze tripod cauldron. From 449 BCE there were also prizes for the leading actors (prōtagōnistēs).

The Writers of Tragedy

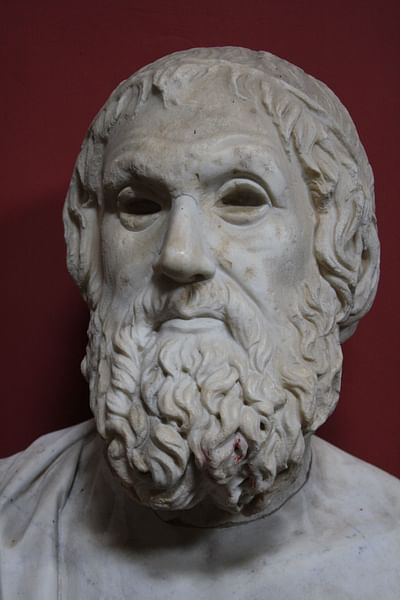

The first of the great tragedian poets was Aeschylus (c. 525 - c. 456 BCE). Innovative, he added a second actor for minor parts and by including more dialogue into his plays, he squeezed more drama from the age-old stories so familiar to his audience. As plays were submitted for competition in groups of four (three tragedies and a satyr-play), Aeschylus often carried on a theme between plays, creating sequels. One such trilogy is Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers (or Cheoephori), and The Furies (or Eumenides) known collectively as the Oresteia. Aeschylus is said to have described his work, consisting of at least 70 plays of which six or seven survive, as 'morsels from the feast of Homer' (Burn 206).

The second great poet of the genre was Sophocles (c. 496-406 BCE). Tremendously popular, he added a third actor to the proceedings and employed painted scenery, sometimes even changes of scenery within the play. Three actors now permitted much more sophistication in terms of plot. One of his most famous works is Antigone (c. 442 BCE) in which the lead character pays the ultimate price for burying her brother Polynices against the wishes of King Kreon of Thebes. It is a classic situation of tragedy - the political right of having the traitor Polynices denied burial rites is contrasted against the moral right of a sister seeking to lay to rest her brother. Other works include Oedipus the King and The Women of Trāchis, but he in fact wrote more than 100 plays, of which seven survive.

The last of the classic tragedy poets was Euripides (c. 484-407 BCE), known for his clever dialogues, fine choral lyrics and a certain realism in his text and stage presentation. He liked to pose awkward questions and unsettle the audience with his thought-provoking treatment of common themes. This is probably why, although he was popular with the public, he won only a few festival competitions. Of around 90 plays, 19 survive, amongst the most famous being Medeia - where Jason, of the Golden Fleece fame, abandons the title character for the daughter of the King of Corinth with the consequence that Medeia kills her own children in revenge.

The Legacy of Tragedy

Although plays were specifically commissioned for competition during religious and other types of festivals, many were re-performed and copied into scripts for 'mass' publication. Those scripts regarded as classics, particularly by the three great Tragedians, were even kept by the state as official and unalterable state documents. Also, the study of the 'classic' plays became an important part of the school curriculum.

There were, however, new plays continuously being written and performed, and with the formation of actors' guilds in the 3rd century BCE and the mobility of professional troupes, the genre continued to spread across the Greek world with theatres becoming a common feature of the urban landscape from Magna Graecia to Asia Minor.

In the Roman world, tragedy plays were translated and imitated in Latin, and the genre gave rise to a new art form from the 1st century BCE, pantomime, which drew inspiration from the presentation and subject matter of Greek tragedy.