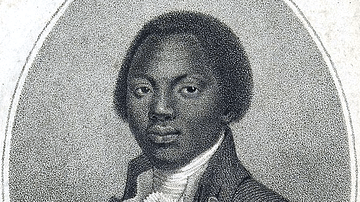

Gustavus Adolphus (l. 1594-1632; r. 1611-1632) was the King of Sweden who elevated his country to a major power in the 17th century. He also is traditionally recognized as the "Father of Modern Warfare" for his military innovations and his tactics have been studied since by generals including Napoleon Bonaparte and George S. Patton.

When he came to the throne at age 16, Sweden was a poor country engaged in three wars it seemed incapable of winning. Guided by his counselor and friend Axel Oxenstierna (l. 1583-1654), Adolphus reversed Sweden’s fortunes by reforming the government and revolutionizing the military, including the creation of a standing, professional army and establishment of a navy. A devout Protestant, he entered the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) against the Imperial Catholic forces in 1630, effectively leading his armies to victory until he was killed at the Battle of Lutzen in 1632.

While he lived, he was known by his birth name, Gustav II Adolph, but two years after his death this was Latinized to Gustavus Adolphus Magnus – Gustavus Adolphus the Great – which is how he has come to be known since. Although born to the noble house and educated at court, he was famous for his ability to communicate cordially with members of every social class, a characteristic that influenced his creation of the cross-trained military in which every unit was valued equally, and each could perform the tasks of any other.

His tactics were studied and implemented, sometimes by his opponents, while he lived and by other great generals since his death up through the present day. The West Point Military Academy of the United States includes the study of his tactics in its curricula, and he also appears in course studies on warfare in other countries around the world today.

Early Life & Kingship

Adolphus was born Gustav II Adolph on 9 December 1594, son of Duke Charles of the House of Vasa (later Charles IX of Sweden, r. 1604-1611) and his second wife Christina of Holstein-Gottorp (l. 1573-1625). The couple were married in 1592 and Adolphus was the eldest of four children. Charles’ first marriage, to Christina’s first cousin Maria of Palatinate-Simmern, had produced six children but only one (Katharina of Sweden) survived to adulthood. Charles was said to have a bad temper which was kept in check by both his wives; a characteristic his son is said to have inherited.

Charles was a staunch Lutheran and, while still a duke, pushed through an agenda making Sweden a Lutheran country to keep the throne from his Catholic nephew Sigismund III Vasa (l. 1566-1632) whose father, Johan Vasa, was king of Sweden until his death in 1592. Sigismund III was at this time King of Poland (from 1587-1632) and when he returned to claim the Swedish crown in 1598, Charles mobilized the country’s forces in a religious crusade against what he characterized as Catholic aggression and drove Sigismund back to Poland. Charles was then declared Charles IX, King of Sweden and, aside from the war he had started with Poland, also managed to start two more: one with Denmark and the other with Russia.

Charles IX had his eldest son tutored by the best minds at court following a Humanistic-Lutheran curriculum. Adolphus became fluent in Latin and Greek as well as Dutch and French while learning German from his mother and, of course, speaking Swedish. He was also tutored in affairs of state and the martial arts, became an expert horseman at a young age, and delivered his first formal address to the court by the time he was 15 years old.

In October 1611, Charles IX died and Adolphus, just shy of his 17th birthday, was too young to rule as the age of maturity for kingship in Sweden was 21. The nobleman Axel Oxenstierna, only 28 at the time but already an influential voice, drafted the Charter of Accession which allowed for Adolphus to rule in conjunction with representatives of the country’s Four Estates – nobles, clergy, burghers, and freeholders – and, this being approved, Adolphus became king, though his coronation would have to wait until his 21st birthday.

Oxenstierna & Reforms

Oxenstierna guided the young king which, as scholar Peter H. Wilson notes, was not always easy:

[Adolphus] was liable to violent outbursts which, though they usually remained verbal rather than physical, were soon regretted. Despite efforts to master his emotions, he remained acerbic and peremptory, but his restless enthusiasm could be infectious. Though he liked to weigh options and take advice, his quick temper often cut in and prompted a sudden change of direction. While he did plan methodically, he remained above all a man of action who personally drilled soldiers, tested new cannon, and sailed warships. (182)

Oxenstierna provided the stability and counsel which enabled Adolphus to set about reforming the government and the military. He streamlined the bureaucracy of governmental offices, creating specific departments to handle the affairs of state such as the admiralty, the army, chancellery, judiciary, and treasury. In reforming the military, he dissolved the secular administration that called up soldiers when needed and mandated conscription records be kept by the local churches of all able-bodied men between the ages of 18-40. One was no longer called by a governmental agency to serve in the armed forces but by one’s church and local priest, thereby associating military service with religious devotion. He also focused on cross-training of the soldiers so that anyone could perform the function of any other resulting in a highly efficient fighting force.

Wilson notes that the praise Adolphus has received for these reforms is similar to that accorded other great leaders such as Frederick the Great and may be exaggerated (187) but, even if that is so, it is clear that Adolphus radically improved the Swedish military from its former state under his father. The national conscription linked with churches, professionally trained officers, and new tactics transformed the Swedish army into one of the most effective fighting forces of its time. His tactics were inspired by Maurice of Orange (also known as Maurice of Nassau, l. 1567-1625) who succeeded his father, William the Silent, as Protestant leader in the Eighty Years’ War (1568-1648).

Maurice drilled his soldiers in the tactic of continuous volleys in which one row of infantry would fire, divide to either side and march to the rear (the countermarch) while reloading, as the second row fired and then did the same. By arranging his infantry in compact formations, by the time the last row had moved up and fired, the first row was ready to step back into place and continue the volley. It is also possible that Adolphus drew on the tactics of the Czech general Jan Zizka (l.c. 1360-1424) who developed the concept of the wagon fort during the Hussite Wars, (1419-c. 1434), enabling one to quickly shift from an offensive position to defense and back.

This is Adolphus’ most famous innovation: the novel use of artillery which operated on the same principle as Zizka’s war wagons in providing an army with mobile defensive-offensive weaponry. Adolphus kept the heavy cannon of the past, which would remain stationary on the field, but had, at first, leather cannon (made of a metal cylinder wrapped in rope and encased in leather which proved unworkable), and then lighter weight copper cannons that could be pulled quickly by a few men or a horse to new positions as the need arose.

Marriage & Wars

Not all of these reforms were implemented in his first few years, however, as he was required to govern the state and, in keeping with tradition, find a woman among the European nobility as a wife. Suitable matches were limited to Protestant women, as Adolphus was Lutheran (though sometimes seems to have allowed people to think he was Calvinist) but he told his mother there was no need for a long search because he had already found the woman he loved: her lady-in-waiting, Ebba Brahe. Ebba Brahe (l. 1596-1674) was Adolphus’ second cousin, once removed, and the two had been corresponding secretly since at least 1613, confessing their love for each other. His mother, who exercised considerable control over her son, rejected this proposal, however, as it did nothing to advance the interests of Sweden.

Adolphus’ mother demanded a dynastic marriage joining their house with foreign nobility and a match was found in Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg (l.1599-1655), daughter of John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, a powerful German noble. The wedding was held in Stockholm on 25 November 1620. Maria was passionately devoted to Adolphus, but their marriage was strained due to her mental instability which manifested in sharp mood swings and verbal attacks. She was only interested in spending time alone with her husband and, as he was busy with affairs of state and then foreign wars, she was frequently depressed, keeping only the company of the ladies-in-waiting who had come with her from Brandenburg.

It is unclear how Adolphus felt about his wife as he left no record and, in his first years as king, there was much to do as he and Oxenstierna had to negotiate the conclusion of the wars of Charles IX. The war with Denmark was ended in 1613 by the Treaty of Knarred which stipulated Sweden pay Denmark a war indemnity and the Russian war was concluded by 1617 but other conflicts required his attention, and he was called away to Latvia shortly after their wedding and many times after. Maria suffered several miscarriages during their marriage but gave birth to a daughter, Christina of Sweden (l. 1626-1689), who Adolphus proclaimed his heir and ordered to be educated as though she were a male.

In 1621, he turned his attention to the conflict with his cousin Sigismund III of Poland which was not as easy to resolve as the wars with Denmark or Russia. Sigismund III still claimed he was the rightful king of Sweden and when Adolphus refused his claim, the conflict broke into the Polish-Swedish War (1626-1629). Adolphus may have hoped to have employed and perfected his military innovations during this conflict but was denied the opportunity repeatedly by his central opponent, the great Polish general Stanislaw Koniecpolski (l. 1591-1646). Adolphus did, however, make use of his new navy which transported the troops and then provided support from the sea.

The Thirty Years’ War

The Polish-Swedish War was far from a resounding Swedish victory but the Truce of Altmark, concluding hostilities in 1629, favored the Swedes because Cardinal Richelieu of France (l. 1585-1642), who was part of the negotiations, needed Adolphus free to intercede in the Thirty Years’ War on the side of the Protestants. The Thirty Years’ War had begun in 1618 as a revolt by Protestants in Bohemia against the Catholic Ferdinand II (l. 1578-1637), Holy Roman Emperor (and related to the Habsburg Dynasty), who had been elected their king. The Protestants wanted another of the legitimate candidates, the Protestant Frederick V of the Palatinate (l. 1596-1632), as their monarch.

Initially a civil conflict confined to Bohemia, hostilities between Catholics and Protestants soon drew the support of the Netherlands for the Protestant cause and Habsburg Spain for the Catholics. The Protestant King Christian IV of Denmark (r. 1588-1648) entered the conflict in 1625 but withdrew in 1629 and Richelieu, though a Catholic, needed another Protestant leader to fight against the Imperial forces of Ferdinand II to weaken the powerful Habsburgs and level the balance of power in the region to favor France.

Christian IV had requested help from Adolphus in 1628, which was sent, but now the Swedish king had his navy transport him and his troops (possibly 20,000) to Pomerania in 1630. In 1621, Adolphus had issued his Articles of War stipulating proper treatment of civilians and property during military campaigns. The two leading generals of the Imperial armies, mercenary leaders Albrecht von Wallenstein (l. 1583-1634), and Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly (l. 1559-1632), had both allowed their troops to plunder villages, mainly because they lacked the funds to pay them. Adolphus prohibited any pillage by his troops (though this still occurred) as well as forbidding wanton destruction of any town or personal property.

Adolphus took special interest in the city of Magdeburg and tried to rally the Germanic princes to ally with him and help the city elders resist Imperial demands. The Germans at this time were wary of Adolphus, however, distrusting his motives and doubting his abilities, especially with such a small army. When Count Tilly besieged Magdeburg in March 1631, Adolphus was engaged in battle and could send no assistance. Magdeburg fell to Tilly and Field Marshal Pappenheim on 20 May 1631 when the city was sacked and almost completely destroyed. Of the 25,000 civilians, less than 5,000 survived and 1,700 of the city’s 1,900 buildings were burned. The Sack of Magdeburg is considered the worst wholesale massacre of the Thirty Years’ War.

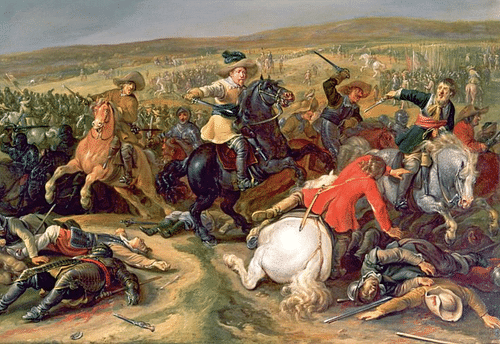

Adolphus struck back at the Imperial forces, meeting Tilly at the First Battle of Breitenfeld in September 1631 where he destroyed Tilly’s army almost completely through a calculated use of cavalry, infantry, and mobile artillery. Tilly lost over 16,000 men killed or captured. Many of those taken prisoner then joined Adolphus’ army. Further victories followed including the Battle of the River Lech (Battle of Rain) in April 1632 in which Tilly was wounded and later died of infection. Wallenstein then became Adolphus’ central opponent holding against him during the prolonged engagement of the Battle of the Alte Veste in September 1632.

On 16 November 1632, at the Battle of Lutzen, Wallenstein adopted Adolphus’ tactics brilliantly but the Swedish forces, supported by German troops, continued to advance successfully. The burning town of nearby Lutzen sent clouds of smoke across the battlefield which contributed to the thick haze from artillery and musket fire, hampering visibility. Adolphus, as usual, was leading from the front and, in the confusion of battle and thick smoke, found himself behind enemy lines with his small entourage. He was shot from his horse and then twice more while his bodyguards were scattered, unaware their king had been killed. No one knew what had happened to him until his horse was seen wandering riderless between the lines.

After his body was found and retrieved, command was assumed by Bernard of Saxe-Weimar (l. 1604-1639) who drove Wallenstein from the field, winning the battle. Afterwards, Bernard turned command over to Axel Oxenstierna who led the forces until accompanying the king’s body back to Sweden.

Conclusion

Adolphus’ widow, Maria, fell into deep grief on hearing of his death and locked herself and their daughter Christina in her bedchambers with the windows blackened. Once his corpse reached Sweden, she demanded the coffin be left open and visited him every day to weep by his side. When Oxenstierna finally ordered the king buried in 1634, he was forced to post guards around the tomb after Maria tried to dig her husband back up.

She continued to mourn her husband until her death from natural causes in 1655. Christina, one of the most highly educated women of her time, patronized the arts lavishly and abdicated the monarchy in 1654 in favor of her cousin Charles who then became King Charles X Gustav of Sweden (r. 1654-1660. Christina then converted to Catholicism, moved to Rome, and continued her patronage of the arts in the interests of the Catholic Counter-Reformation (1645-c.1700).

The Thirty Years’ War had no winner. The Peace of Westphalia of 1648 concluded hostilities and, as far as resolving the conflict between Catholics and Protestants, simply reasserted the provisions of the Peace of Augsburg of 1555 by which the ruler of a kingdom or territory chose its religion. Adolphus’ death in 1632 is among the great What-Ifs of history in that, had he lived, the Protestant faction might have won a decisive victory. Wallenstein was already on uncertain ground with Ferdinand II prior to Lutzen and, after his defeat, was assassinated by his officers. It is likely, with both Tilly and Wallenstein dead, Adolphus could have won the war.

This, of course, is speculation and, although Adolphus is regularly praised as a great military leader and innovator, many modern-day scholars argue that his reputation is overrated in that his record of victories in any of the battles fought between 1621-1632 is less impressive than many others who do not enjoy the same level of recognition. The debate on Adolphus’ overall legacy continues but there is no denying his role in revolutionizing warfare in the Early Modern period or the honor due him in elevating Sweden to a major political and military power. He continues to be honored for his achievements in the present day, especially in Finland and Sweden where Gustavus Adolphus Day is celebrated annually on the date of the great king’s death.