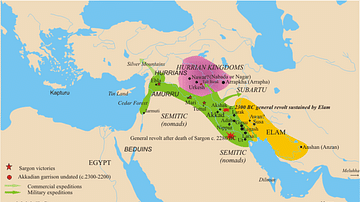

The Gutians were a West Asiatic people who are thought to have lived around the Zagros Mountains in a region referred to as Gutium. They had no written language and all that is known of them comes from their enemies, including the Akkadians, Sumerians, and Assyrians, who blame them for the destruction and desolation of the land.

Ancient texts hold them responsible for the fall of the Akkadian Empire and the desolation of Sumer. They are first mentioned in Akkadian texts under the reign of Shar-Kali-Sharri (r. 2223-2198 BCE) one of the last kings of the empire founded by Sargon the Great of Akkad (r. 2334-2279 BCE) and appear in accounts of the reign of his grandson, Naram-Sin (r. 2261-2224 BCE) as well as being referenced in later works of Mesopotamian Naru Literature, notably The Legend of Cutha and The Curse of Agade.

After the fall of the Akkadian Empire, the Gutians claimed succession and ruled in Sumer (though how widely is disputed) until the king of Uruk, Utu-Hegal (c. 2055-2047 BCE) led a revolt against them. After Utu-Hegal drowned, the kingship passed to Ur-Nammu (r. 2047-2030 BCE) of Ur who continued the war, and when he was killed in battle, his son Shulgi of Ur (r. 2029-1982 BCE) concluded hostilities, driving the Gutians from the land.

Later Assyrian texts refer to the Medes as Gutians, and it is thought the term came to be used to designate any group considered 'uncivilized' or 'barbaric' by the scribes who wrote the histories. Since the Gutians themselves left no records, their poor reputation as nomadic barbarians, killing innocent people and destroying cities wantonly, has gone largely unchallenged. Only recently have scholars begun to consider the possibility that the Gutians may not have been as bad as they are depicted, but still no evidence exists to support that.

Akkad & the Gutians

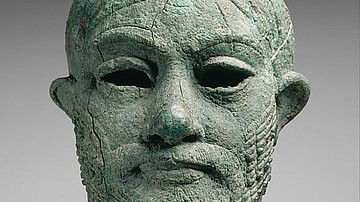

The Gutians are first referenced in relation to the fall of the Akkadian Empire. Sargon of Akkad established the first multinational, multiethnic political entity in the world in Mesopotamia and maintained control through carefully placed officials in various cities and military strength. The empire expanded during the reign of Naram-Sin, considered the greatest Akkadian king, who campaigned against the Gutians and defeated them in battle. Even so, the accounts claim that it was a costly victory and the Gutians were able to regroup afterwards.

Who they were, and where precisely they came from, is unknown. All the ancient accounts say is that they came from the Zagros Mountains, north of Elam, in what is now Iran, but these accounts do not seem to reference the same people. Scholar Marc van de Mieroop comments:

The geographical name Gutium, and the indication of people as Gutians, is attested in the Mesopotamian record from mid-third to the late first millennium BCE. It is highly improbable that the name Gutians always referred to the same group of people and Gutium to the same region. Evidence from the second and first millennia mostly suggests an eastern location from a Mesopotamian point of view, but we cannot say that this was true earlier when the Gutians were most important in Mesopotamian history. (Gutians, 1)

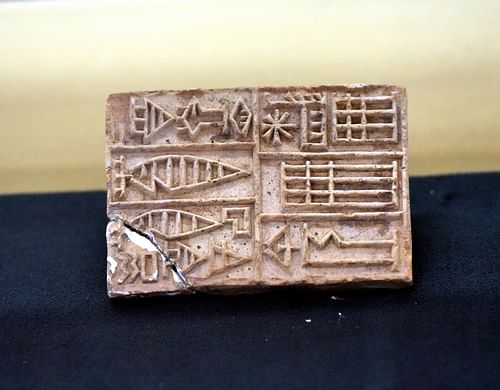

They are first mentioned as nomadic raiders engaging in hit-and-run raids on the cities under Akkadian rule. Their kings are included in the Sumerian King List, so they apparently had some form of government, but what this consisted of is unclear. By 2218 BCE, the Gutians had established themselves in Sumer, though to what extent is unknown, and by 2083 BCE, they are blamed for the fall of the Akkadian Empire. The time between 2218-2047 BCE is known as the Gutian Period in Sumerian history when the foreigners held power before they were challenged by Utu-Hegal.

Sumer & the Gutians

As with all other aspects of the Gutians, it is unknown how – or even if – they conquered Sumer in battle, but later scribes blamed them for widespread devastation and death. Scholar Paul Kriwaczek notes how modern-day archaeological excavations at various sites in Mesopotamia show no signs of human occupation between the fall of Akkad and the revival of Sumer under Ur-Nammu and goes on to relate how the Gutians were held responsible for this by the Sumerian scribes:

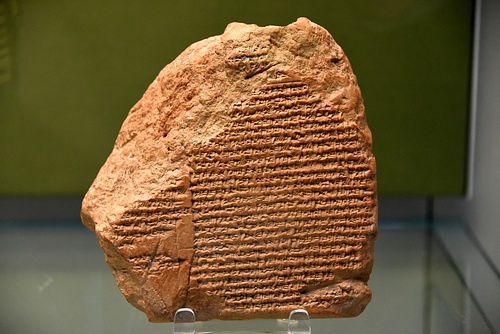

The guilty party was named by the ancients as the Gutians, who swept down from the upper Diyala Valley leaving devastation in their wake. "Kingship was taken to the hosts of Gutium who had no king," says the King List. A later poetic lament, The Cursing of Agade, explains that the god "Enlil brought out of the mountains those who do not resemble other people, who are not considered part of the Land, the Gutians, an unbridled people, with human intelligence but with the instincts of dogs and the appearance of monkeys." The catastrophe they visited on Akkad was merciless: "Nothing escaped their clutches, no one avoided their grasp. Messengers no longer traveled the highways, the courier's boat no longer passed along the rivers. Prisoners manned the watch. Brigands occupied the highways. The doors of the city gates of the Land lay dislodged in mud and all the foreign lands uttered bitter cries from the walls of their cities." (129-130)

Kriwaczek points out how early historians accepted these accounts as entirely factual but how it is possible that climate change, bringing drought and famine, was primarily responsible for the fall of Akkad; the Gutians then just exploited that weakness. The breakdown of social norms and customs referenced in the accounts might also have been the result of famine and the inability of local governments to deal with widespread starvation and the devaluation of currency. Kriwaczek notes how "it seems very unlikely that the Gutians alone were able to overwhelm the empire by force of arms. Akkad had previously had little difficulty in resisting assault by much better organized enemies" (130). It seems possible, then, that environmental changes gave the Gutians the upper hand in conquest just when they needed it.

At the same time, however, there is no way to definitively state this. Archaeological evidence does suggest climate change during this period, but whether that resulted in famine or the social unrest detailed in the ancient records is unclear. The later Akkadian kings were not as strong as Sargon and Naram-Sin had been, and Naram-Sin's son, Shar-Kali-Sharri, fought nearly continuous wars against the Amorites, Elamites, and Gutians throughout his reign. The last kings of Akkad held only the area around their central city and are not referenced as monarchs of an empire, only a kingdom. It would seem that Akkad, in this weakened state, would have been easy prey for the Gutians even without climate change or any other factors.

Gutian Kings & Sumerian Renaissance

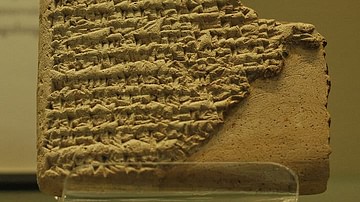

The first Gutian king mentioned as ruling in Sumer is Imta (also given as Nibia, c. late 3rd millennium BCE) who was succeeded by Inkishush, the first to appear on the Sumerian King List. He ruled for six years, but from where or how far his influence reached is unknown. He was succeeded by Sarlagab who may have been the same king captured by Shar-Kali-Sharri, but this, also, is unclear. 16 other Gutian kings appear on the Sumerian King List, each ruling no more than seven years and some only one or two, until Tirigan, who reigned for only 40 days until he was unseated by Utu-Hegal c. 2050 BCE.

According to the Victory Stele of Utu-Hegal, the Sumerian king refused to negotiate with Tirigan and imprisoned his emissaries. Tirigan fled with his wife and children when he understood Utu-Hegal had the upper hand but was apprehended and, afterwards, probably executed. The stele only says "Utu-Hegal made him lie at his feet and placed his foot on his neck" but provides no further details other than that Utu-Hegal restored the kingship of Sumer and "defanged the serpent Gutians of the mountains". Utu-Hegal then seems to have committed some sort of sin against Marduk, patron god of Babylon, which caused him to be drowned ("so the river carried off his corpse") and the kingship passed to Ur-Nammu of Ur.

Ur-Nammu initiated the so-called Sumerian Renaissance of the Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE) during which he engaged in a number of building projects, reinvigorated the economy, and issued his set of laws, the Code of Ur-Nammu, the oldest law code in the world. Ur-Nammu was killed in battle with the Gutians, and his son, Shulgi of Ur, continued the war against them, finally driving them from Sumer early in his reign.

The Legend of Cutha

The Gutians were not defeated, however, and just returned to wherever they lived near the Zagros Mountains to the north. They lived on in the genre now known as Mesopotamian Naru Literature which featured a well-known figure from the past – almost always a king – in a fictional drama conveying some important lesson or moral. In The Curse of Agade, for example, Naram-Sin is held responsible for the fall of Akkad after, receiving no answer to his prayers, he attacks the temple of Enlil, and the gods remove their grace from the city, allowing the Gutians to destroy it. The lesson in this tale is that one should accept whatever one receives from the gods – even silence in response to supplication – and should never question their ways.

In The Legend of Cutha, Naram-Sin appears again as the main character in a story with a similar theme. Here, Naram-Sin’s kingdom is invaded by terrible, superhuman entities who destroy villages and towns seemingly for no reason. These creatures are associated with the Gutians through an echo of their barbarism as recorded by Sumerian scribes but are not named as Gutians. In fact, Gutium is one of the lands mentioned as having been ravaged by the creatures before they reach Akkad. Naram-Sin sends one of his soldiers to prick one of the monsters since, if it bleeds, it can be killed. Once he hears the creatures bleed, he consults the gods on when and where he should attack.

The gods reply that he should hold his place and do nothing at all, which he finds unacceptable, and he sends out an army of 120,000 troops, none of whom return. He then sends out 90,000 troops who are also killed and then 60,700 troops who meet the same fate. Naram-Sin understands he has offended the gods and humbles himself before them. Afterwards, he captures 12 enemy soldiers but does not proceed against them until he has consulted the gods. When he is told not to harm them because Enlil has plans to destroy them in his own way, he hands them over to Enlil's temple. The story ends with Naram-Sin addressing the audience directly, telling them to obey the gods and not rely on their own understanding since humans cannot know what the divine has planned.

The tale seems to have been popular in the 2nd millennium BCE, long after Akkad had fallen, and Naram-Sin and the other Akkadian kings had become folk heroes. The association of the Gutians with the superhuman monster army makes clear that they were still regarded as inhuman enemies of the gods who only existed to destroy civilized lands and would, in time, receive justice at the hands of the divine will. It is likely the story resonated with a Sumerian audience at this time because Sumer had fallen to the Elamites in 1750 BCE and was then invaded by the Amorites who, in merging with the indigenous population, ended Sumerian culture or, at least, had a hand in its decline. Van de Mieroop comments:

The exact role of the Amorites in the overthrow of the Ur III state is difficult to discern but we can see a parallelism with the Gutians' role in the end of the Akkadian state. Both groups came from outside the region, acquired political importance, and were later regarded as crucial in the overthrow of the existing political situation. (A History of the Ancient Near East, 83)

Stories like The Legend of Cutha and The Curse of Agade perpetuated the image of the Gutians as the 'other' who is to be feared and hated for bringing unwelcome change. By the time The Legend of Cutha was written down, it is believed, the story had existed orally for some time, and the Gutians were firmly entrenched in Mesopotamian lore as the enemy of both the people and the gods. Van de Mieroop elaborates:

[The Gutians] are always portrayed in extremely negative terms: They do not perform proper religious rites and abuse the people of Babylonia by taking away the wife from the husband, the child from the parent. One literary text from the early second millennium calls them "of human face, dog’s cunning, monkey’s build". We can thus conclude that, for a while, parts of Babylonia were politically controlled by people called Gutians who were perceived as foreign and barbaric by the native population. (Gutians, 3)

Van de Mieroop goes on to make clear, however, that there is no way of knowing whether this perception is valid. Were the Gutians actually as bad as they are depicted or were they maligned by scribes who objected to foreign domination and unfamiliar traditions and rites? Unfortunately, there is really no answer to that question.

Conclusion

The Gutians continued to play a part in Mesopotamian history after they were driven out by Shulgi of Ur. The Assyrians designate the Medes as Gutians, supporting the modern-day theory that 'Gutian' became a default term for anyone foreign and understood as dangerous or threatening. The Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE) blamed 'the Gutians' for inciting rebellion in Babylon and the later Babylonian king Nabonidus (r. 556-539 BCE) claimed they were responsible for the destruction of the temple in the city of Sippar.

In 539 BCE, when Cyrus II (The Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE) of the Achaemenid Empire took Babylon, he employed Gutian mercenaries and may have done so in other campaigns as well. After the Achaemenids conquered Mesopotamia, however, the Gutians vanish from history. Their name seems to have lived on in references to 'barbarians' but, as noted, it is unlikely the later 'Gutians' were the same people held responsible for the fall of Akkad or the desolation of Sumer.

Van de Mieroop observes, "While many references to Gutians and Gutium can be collected, they do not allow us to write the history of a people or a country" (Gutians, 3). This claim is, unfortunately, the most accurate statement concerning the Gutians. Although modern-day scholarship has attempted to link them with ethnic Kurds, this is not possible since no one can say with any certainty who the Gutians were, and until more information on them comes to light, this situation will remain unchanged.