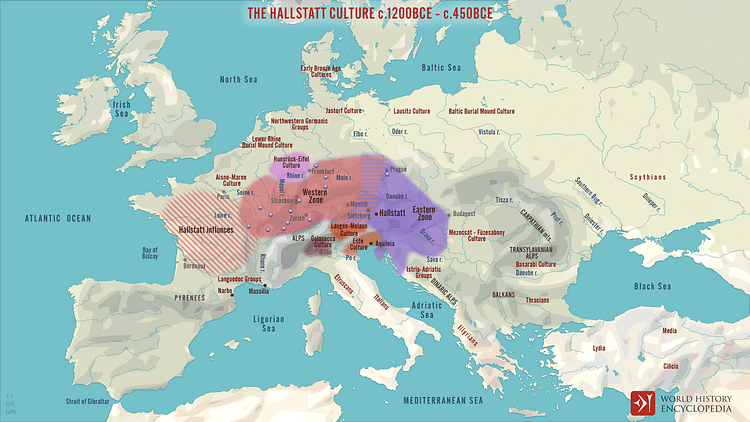

The Hallstatt culture is named after the site of that name in Austria and it flourished in central Europe from the 8th to 6th century BCE. The full period of its presence extends from c. 1200 to c. 450 BCE - from the Late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age.

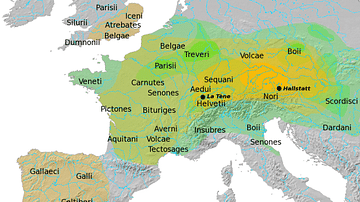

Due to cultural similarities with later Iron Age peoples in Europe, the Hallstatt culture is often called a proto-Celtic culture. The Hallstatt culture went into decline from around 500 BCE as local natural resources, in particular, salt, ran out and rival trading centres appeared elsewhere. The Hallstatt culture was replaced in terms of regional dominance by peoples living to the north, west, and east, known collectively as the La Tène culture (c. 450 - c. 50 BCE), when cross-European trade routes shifted from the Hallstatt area.

Time & Geography

The Hallstatt culture derives its name from the site on the west bank of Lake Hallstatt in Upper Austria where the first artefacts were discovered in 1846 CE. Traditionally, the culture was divided into two approximate periods spanning from 750-600 BCE and from 650 to 450 BCE. More recently, archaeological finds have demonstrated the culture began earlier than first thought and so the full span of the Hallstatt culture is now divided into four periods (A, B, C, and D), beginning around 1200 BCE and ending around 450 BCE. However, these dates are the broadest possible range and are not agreed upon by all scholars, neither can they be applied to all areas where the culture was present.

What is more certain is that, eventually, the culture spanned out from Hallstatt to the east and west, covering territory in what is today western Austria, southern Germany, Switzerland, and eastern France on the one side, and eastern Austria, Bohemia, and parts of the Balkans on the other. It was the western side of this area that would eventually develop into what we might today call the ancient Celts. Just how the Hallstatt culture spread is another point of uncertainty. Migration was traditionally suggested as the answer but more modern historians prefer a nuanced explanation that includes such activities as trade, tribal alliances, intermarriages, imitation, and so on, all of which can be difficult to trace in the archaeological record.

Iron & Salt

Two developments were responsible for the success of the Hallstatt culture. The first came around the beginning of the 1st millennium BCE and spread over the next two or three centuries in what is sometimes called the Urnfield period (1300-800 BCE and equivalent to Hallstatt A & B) after the practice of burying cremated remains in urns. Iron smelting technology and know-how saw the Hallstatt culture make a leap forward in terms of making stronger metal objects. Iron was used to make better tools, sturdier agricultural equipment, stronger metal-rimmed wheels, and sharper and more durable weapons like iron swords than in the preceding Bronze Age. The abundance of local iron also meant that it could be traded as raw material, and this was typically done in the form of ingots shaped like a double pyramid or simple rods weighing up to 9 kg (20 lbs) each.

The second factor in the prosperity of the Hallstatt culture was the exploitation of local rock salt deposits. Salt was needed to preserve meat, and it was traded with neighbouring cultures. Salt was first extracted from natural briny springs using evaporation, but from the 8th century BCE, the much more efficient method of salt mining was used. The passages of the salt mines at Hallstatt run for 3,750 metres (4,100 yards), go down to a depth of 215 metres (700 ft), and span an area of 30,000 square metres (320,00 square feet).

Artefacts related to the mining of salt have been preserved by the high content of salt in the soil around Hallstatt. These objects include picks, leather sacks for carrying rocks, and resinous torches. Copper was another precious raw material found in this region and then exported.

With salt and iron to trade, the Hallstatt culture was well placed geographically to transport these materials elsewhere. The culture was located in the centre of established trade routes, which had been in use since at least the Bronze Age with goods being transported along waterways which, in turn, led to some of Europe’s major rivers. The culture also benefitted from the expansion of the Mediterranean states to the south, especially the Greek colonies in southern France and the Etruscans in north-central Italy, who became ever-more interested in trade contacts with the peoples in central Europe.

Material Culture

The principal archaeological remains of the Hallstatt culture are the fortified buildings and tombs of the society’s elite. Both of these types of structure were built at what historians often call ‘princely seats’, indicating the belief that Hallstatt communities were centred around local princes and aristocracies that ruled over and controlled the economic resources of their tribe. These sites are typically located on hilltops and they show evidence of narrow streets lined with small residences, larger residences of timber, and concentrated areas of workshops. That trade was booming is indicated by the quantity of foreign goods excavated such as eastern drinking horns, Etruscan bronze vessels, fine Greek pottery, and silk from the eastern Mediterranean.

Pottery was made locally across the region, and the production of wares for feasting indicates that this was an important part of the culture. Jars, dishes, and drinking vessels were decorated with often severe geometric motifs, which were incised, stamped, or painted using ochre or graphite. There were, too, differences within the Hallstatt region, such as plainer pottery in the east and more decorative in the north. Brooches are another common find, and these, too, illustrate regional variations, most likely reflecting different types of clothing. Birds, especially water birds like ducks and swans, and bulls feature prominently in Hallstatt art, best seen in small bronze or iron sculptures, which were likely made as votive offerings. Objects like these and even bronze bowls for cooking display a high degree of technical expertise in their manufacture.

Burials

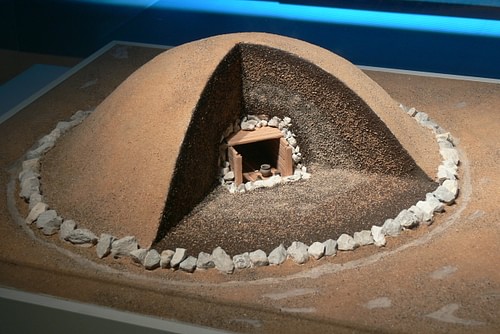

Although there is evidence of cremations deposited in modest graves, the tombs of the Hallstatt elite illustrate that they had the ability to employ a great deal of organised labour in their construction. A typical tomb is composed of a wood-lined inner chamber enclosed in a huge mound of earth. An excellent example is the Horchdorf tomb near Baden-Württemberg in southwest Germany, which dates to the second half of the 6th century BCE. Once part of a burial mound since levelled and reconstructed, the tomb itself was undisturbed when excavated. The wooden walls of the chamber room were made of oak logs, each wall measuring around 4.7 metres (15.4 ft) in length. Inside was a single male occupant, aged around 40, who was placed on a bronze couch.

Also in the tomb were a four-wheeled waggon with horse trappings, a conical hat made of birchbark, a quiver of arrows, and hooks for fishing. Precious goods include gold additions to the man’s clothing and leather boots, a gold bracelet and necklace, an amber necklace, fine drinking vessels (some contained mead), dishes, and a massive bronze cauldron with lion decorations. The cauldron is of Mediterranean origin and illustrates the trade then going on between the Hallstatt peoples and neighbouring cultures. The only weapon in the tomb was a knife, and this is a point of distinction compared to Celtic tombs in later periods. Curiously, a life-size sandstone sculpture of a warrior was found nearby, and he wears the same type of hat as found in the tomb. The stone figure perhaps once stood guard over the princely tomb and may even have represented its occupant.

Another well-documented site is the fortified hilltop settlement at Heuneburg on the west bank of the Danube in southeast Germany. In the 6th century BCE, the site was given a 600-metre (1968 ft) long mud-brick wall set upon a stone base and punctuated with square towers. The wall is 4 metres (13 ft) high in places. The stone needed for this large-scale project was quarried from a source of limestone 6.5 kilometres (4 miles) away. Evidence of archaeological finds and building techniques strongly suggest contact had been established with the Etruscans. Spread around the fortified area are 11 tumuli containing a rich array of goods.

The Vix tomb dates to the last stage of the Hallstatt period, perhaps the early 5th century BCE. Located near Châtillon-sur-Seine in northeast France, this burial contained the remains of a female and indicates that women could be just as honoured as men in terms of the care and cost of their burials. Inside the mound was the now-familiar wood-lined chamber, and inside this were a four-wheeled waggon, a massive gold torc, many other items of jewellery, and the famous Vix Krater. This krater is made of bronze, measures 1.64 metres (5.4 ft) in height, and has a capacity of 1100 litres (242 gallons), making it the largest example of its kind to survive from antiquity.

Decline & La Tène Culture

From around 600 BCE, there is a marked increase in the use of fortifications, both for the village-like settlements and some individual groups of residences. Another development is the concentration of power and wealth in fewer settlements. These changes were likely a symptom of an increase in competition for resources and wealth, particularly as the Mediterranean cultures presented ever-more trading opportunities. Towards the end of the Hallstatt period, the number of large burials with precious goods deposited in them increases, so the culture was still prospering but then something happened that sent these peoples into a decline. We do know that the production of salt at Hallstatt ended c. 400 BCE. It is possible that the Hallstatt elite, now long used to the luxury goods that trade brought, moved away to other sites in order to maintain the living standard to which they had become accustomed. Alternatively, the peoples of western Europe established their own trade networks with the Mediterranean cultures and so replaced the Hallstatt as the primary market of traders from Etruria and the Greek colonies in southern France.

The Hallstatt culture was replaced in terms of wider regional dominance by the La Tène culture, named after the site of that name on the northern shores of Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland. The two cultures may well have overlapped for a generation (c. 460-440 BCE). There are very few sites which display any continuity between the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures; one notable site where the two are linked is Hohenasperg in southern Germany. It seems, then, that trade routes in central Europe shifted as new resources were discovered elsewhere, new settlements prospered alongside these routes, and the Hallstatt sites quietly slipped into historical obscurity, their story not to be rediscovered for 23 centuries.