The Han Dynasty (202 BCE - 220 CE) was the second dynasty of Imperial China (the era of centralized, dynastic government, 221 BCE - 1912 CE) which established the paradigm for all succeeding dynasties up through 1912 CE. It succeeded the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE) and was followed by the Period of the Three Kingdoms (220-280 CE).

It was founded by the commoner Liu Bang (l. c. 256-195 BCE; throne name: Gaozu r. 202-195 BCE) who worked toward repairing the damage caused by the repressive regime of the Qin through more benevolent laws and care for the people. The dynasty is divided into two periods:

- Western Han (also Former Han): 202 BCE - 9 CE

- Eastern Han (also Later Han): 25-220 CE

The separation is caused by the rise of the regent Wang Mang (l. 45 BCE - 23 CE) who declared the Han Dynasty finished and established the Xin Dynasty (9-23 CE). Wang's idealistic form of government failed and, after a brief period of turmoil, the Han Dynasty resumed.

Gaozu initially retained the Qin Dynasty's philosophy of Legalism but with less severity. Legalism gave way to Confucianism under the most famous monarch of the Han, Emperor Wu (also given as Wudi, Wuti, Wu the Great, r. 141-87 BCE) who, among his many other impressive achievements, also opened the Silk Road, establishing trade with the West. The Han also negotiated a peace, which was more or less observed, with the nomadic peoples of the Xiongnu and Xianbi to the north and the Xirong to the west which stabilized the borders and encouraged peace and cultural development in the arts and sciences. Many of the commonplace items taken for granted today were invented by the Han such as the wheelbarrow, the compass, the adjustable wrench, seismograph, and paper, to name only a few.

The Han also restored the cultural values of the Zhou Dynasty, which had been discarded by the Qin, encouraged literacy, and the study of history. The historian Sima Qian (l. 145/35-86 BCE) lived during this period whose Records of the Grand Historian set the standard and form for Chinese historical writings up through the 20th century CE. Chinese mythology and religion also developed during this time including the popular messianic movement focused on the Queen Mother of the West.

By c. 130 CE, however, the imperial court had become corrupt with eunuchs exercising more actual power than the Chinese emperor. By the time of the emperor Lingdi (r. 168-189 CE), the Han royal house had less actual authority than the palace eunuchs and the generals (who were more or less autonomous warlords) stationed at the borders of the country. In 184 CE, the Yellow Turban Rebellion broke out in response to high taxes and famine and these generals put it down.

Among them was Cao Cao (l. 155-220 CE) who, afterwards, waged war against his fellow commanders for control of the state. He was defeated at the Battle of Red Cliffs in 208 CE after which the country was divided between three kingdoms and the Han Dynasty fell. Its legacy is so profound that it continues to the present day and the majority of ethnic Chinese refer to themselves as Han People (Han rem) proudly in identifying themselves as descendants of the great ancient dynasty.

The Qin Dynasty's Rise & Fall

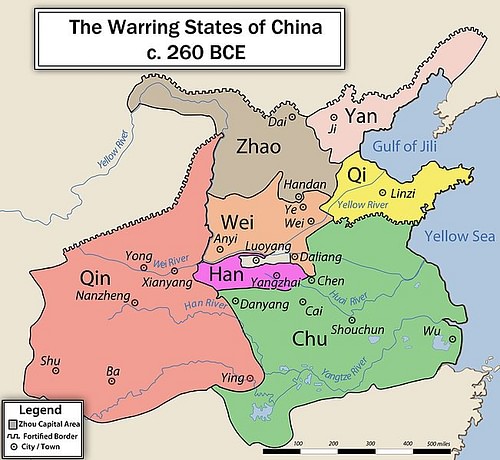

The Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) established itself as a decentralized government in which lords, loyal to the king, ruled over separate states. Initially, this form of government worked well but, in time, the states grew more powerful than the central Chinese government and each tried to claim from the Zhou the Mandate of Heaven.

The Mandate of Heaven was a concept originally conceived during the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE) and developed by the Zhou which maintained that a monarch's reign was legitimized by divine powers which had made an agreement with him: he would rule with their blessing as long as he cared for the welfare of his subjects. When it seemed the monarch and dynastic house cared more for themselves than the people – evidenced by social and economic turmoil – it was understood they had lost the Mandate of Heaven and should be replaced.

The seven separate states fought each other for supremacy – which would grant them the mandate – throughout the era known as the Warring States Period (c. 481-221 BCE) but none could gain the advantage until the state of Qin, under their king Ying Zheng, adopted a policy of total war and defeated the others. Ying then proclaimed himself Shi Huangdi (“First Emperor”) and founded the Qin Dynasty in 221 BCE. At first, Shi Huangdi seemed to observe the Mandate of Heaven in caring for the people but became increasingly oppressive and tyrannical. By 213 BCE, people were being conscripted to work on his projects and essentially serve as slave laborers while freedom of speech was banned and any books other than those on Qin history, Legalism, or practical matters were burned.

When Shi Huangdi died in 210 BCE, his weak son, Qin Er Shi (r. 210-207 BCE) succeeded him but could not maintain the empire against rebellion. The rebel forces were led by the noble Xiang Yu of Chu (l. 232-202 BCE) who ennobled the commoner Liu Bang of Han as King of Han. Liu Bang accepted the surrender of the last Qin emperor, Ziying (d. 206 BCE), and treated him and his family courteously but Xiang Yu ordered them all executed.

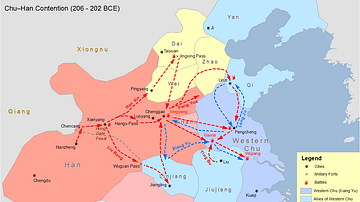

This was far from the first time the two men had disagreed (they had been sparring with each other for over a year by this time), and their ambition to become sole ruler of China ignited the conflict known as the Chu-Han Contention (206-202 BCE) which was resolved in Liu Bang's favor at the Battle of Gaixia in 202 BCE. Xiang Yu's forces were defeated; he committed suicide afterwards. Liu Bang (known later as Gaozu) was now the supreme ruler of China and founded the Han Dynasty.

Western Han

He initially rewarded the generals Han Xin, Peng Yue, and others who had helped him defeat Xiang Yu, with grand estates and their own kingdoms but later grew suspicious of them and had them all executed, possibly at the urging of his ambitious wife, Empress Lu Zhi (l. 241-180 BCE). He first established his capital at Luoyang but then moved it to Chang'an for defensive purposes. With no experience in government, Gaozu had to rely on earlier models and so adopted the decentralized government of the Zhou and the Legalism of the Qin (though the latter was implemented more benevolently). The decentralized state was divided into 13 administrative districts known as commanderies (also as jun) and awarded ten kingdoms to members of his family whom he expected to rule justly.

The Qin Dynasty had misused the Mandate of Heaven to repress the people for the greater glory of the Chinese emperor and Gaozu took steps to make sure he would not make the same mistake. As a former commoner, he understood the life of the peasantry and initiated programs, such as lowering taxes and opening up bureaucratic positions to all classes, to provide people with upward mobility.

Gaozu died in 195 BCE and was succeeded by three puppet kings controlled by Empress Lu Zhi: Hui (r. 195-188 BCE), Qianshao (r. 188-184 BCE), and Houshao (184-180 BCE). Empress Lu Zhi was the power behind the throne during this time and was so feared that no one questioned her policies. When she died, the nobles had her entire family executed and chose one of their own, Wen (r. 180-157 BCE), as emperor who is considered among the most effective monarchs of the Han.

The Han Dynasty was still operating at this time as a decentralized state along the lines of the Zhou and under Wen's son, Emperor Jing (r. 157-141 BCE), the states' threat to the throne was recognized as their power grew. Jing understood it was only a matter of time before they rebelled and accused the rulers of the states and officials of commanderies with various offenses and decreased their territory.

His actions resulted in the Rebellion of the Seven States of 154 BCE. Jing's imperial forces defeated the rebels and restored order, but it was clear that a decentralized state would work no better for the Han than it had for the Zhou. Jing centralized the government and instituted other measures to keep the states in line. The reigns of Wen and Jing are often referred to as a “golden age” of Han history for their stability and cultural advances and, had they been weaker monarchs, the Han Dynasty would have ended with the Rebellion of the Seven States.

Jing was succeeded by his son Wu who is usually referenced as Wu the Great for his expansionist policies and reforms. His early reforms opened up possibilities for the lower class that had never existed before in governmental positions, curtailed the greed of the nobles, and expanded the law code so that all were equal under the law. These reforms were rejected by the nobles and, especially by Wu's grandmother who was a powerful influencer at court. Wu got around their objections by creating his “insider court” comprised of commoners he elevated to important government positions to act on his suggestions for reform without them being officially approved. When his grandmother died, he was able to implement the reforms openly, including the adoption of Confucianism as the national philosophy.

He also engaged in a policy of expansion in every direction, defeating the Xiongnu in the north and conquering the regions of modern-day Korea and Vietnam. In 130 BCE, he opened up the Silk Road, establishing trade with the West, and initiating cross-cultural transmission, and encouraged the expansion of the Cult of the Queen Mother of the West which inspired religious, philosophical, and literary works on immortality and the meaning of life.

During Wu's reign, the Cult of the Queen Mother of the West became so popular that shrines to her multiplied throughout China. The Queen Mother of the West first appears in the inscriptions on oracle bones from the Shang Dynasty and she continued to be invoked throughout the Zhou and Qin dynasties. She is also known as Golden Mother of the Jade and was a goddess of prosperity and eternal life.

Stories circulated that the Queen Mother of the West met secretly with Wu on the sacred night of the 7th day of the 7th month, sharing her secrets with him, which accounted for the wisdom of his reign. Scholar Patricia Buckley Ebrey notes that “this movement was the first recorded messianic millenarian movement in Chinese history” (73) and encouraged the further development of the concepts of life after death, eternity, and ultimate meaning regardless of what trials one might be suffering through. Worship of the Queen Mother of the West often took the form of passionate outbursts and prophetic visions, one of which was said to foretell the coming fall of the Han.

Xin Dynasty & Eastern Han

This fall came to pass after the last of the eight Han monarchs who followed Wu when the nephew of empress Wang Zhengyuan (l. 71 BCE - 13 CE), Wang Mang, was appointed regent for a young heir to the throne, swore he would surrender control when the boy came of age, but then seized power instead and established the Xin ("new") Dynasty. Wang was a Confucian scholar and idealist who believed that a single, strong ruler with a clear vision and the freedom to do as he pleased would be more effective than one who took counsel and had to discuss policy with others before implementing it. He therefore became, essentially, a one-man government and attempted to do everything himself.

Since he did not trust others, he refused to delegate responsibilities and so the government payroll, which was supposed to have been reformed, was neglected and officials were working without pay. This encouraged corruption because, in order to buy necessities, these officials began charging citizens for services that should have been free as well as accepting bribes. Wang meant well in trying to fully implement Confucian ideals in government policy but had neither the experience nor the character to govern effectively.

He instituted state ownership of forests to provide access to all, built public halls for rituals and public granaries for food distribution, and cut the court's budget in order to provide more funds for public programs. His inability to delegate, however, and his unrealistic vision of himself and what he could accomplish, eventually led to his downfall. The people grew frustrated with his ineptitude and a mob overran the palace, hacked him to pieces, and used his head as a kickball.

After Wang's death, a prince named Liu Xuan took the throne (the so-called Gengshi Emperor, r. 23-25 CE) but he was weak and was deposed during the Red Eyebrows Rebellion (so-called because the rebels painted a stripe of red over their eyebrows). His reign is usually dismissed by scholars as an aberration of the rebellion and the period of the Eastern Han begins with the reign of Emperor Guangwu (r. 25-57 CE). Guangwu moved the capital back to Luoyang and instituted a number of reforms to prevent the kind of chaos of the Xin Dynasty from happening again.

Guangwu's reforms enabled the continuation of the Han Dynasty but the Han ruling house fairly quickly devolved into a series of monarchs who cared more about indulging their pleasures than ruling a country. Emperor An (r. 106-125 CE) turned over his responsibilities to the palace eunuchs and preferred to drink all day. His successor, Shun (r. c. 125-144 CE), was equally inept and so corrupt that his reign inspired the Five Pecks of Rice Rebellion of 142 CE. Huan (r. 146-168 CE), who followed Shun, was so lazy and incompetent that when a group of students demanded he do something to remove and punish corrupt officials, he found it easier to have the students arrested and leave the officials in place.

The Eastern Han continued on this downward trajectory, with eunuchs and corrupt officials making political decisions and appointing inept relatives to important bureaucratic positions. At the same time, the Han was funding their expansionist policies in Vietnam and Korea while also defending against raids by the Xianbi along the borders. These campaigns were not only costly, requiring higher taxes to pay for them, but necessitated a strong military presence in border regions which empowered the generals stationed there at the expense of the emperor who became more and more isolated.

Under Huan's successor, Lingdi, floods, famine, and exorbitant taxes led to the Yellow Turban Rebellion of 184 CE, which these generals put down, ostensibly in his name but actually for their own self-interest, further weakening imperial authority. Among these generals was the warlord Cao Cao who then went to war against the other commanders in an attempt to unify China under his reign. He was defeated at the Battle of Red Cliffs in 208 CE which left the country divided into the Period of the Three Kingdoms – Cao Wei, Eastern Wu, and Shu Han – each claiming the Mandate of Heaven for themselves and signaling the end of the Han Dynasty.

Conclusion

The Han Dynasty began as a kind of experiment in government as Gaozu and his advisors tried to find a balance between the overly trusting policies of the Zhou and the paranoid repression of the Qin with no model to work from. The Han inherited the vast territory that the Qin had held together with excessive brute force and that the Zhou had lost through too little. In trying to strike the perfect balance, they encouraged the concept of innovation among the people.

The Han developed music theory by c. 180 BCE, the seismometer was invented in 132 BCE, paper by c. 105 BCE, the waterwheel for producing power was in use by 40 BCE. The calendar, mathematical and medical treatises, cartography, metallurgy, architecture, astronomy, and many other disciplines, concepts, and items of common and uncommon usage were invented or developed by the Han. The Silk Road created a direct link to the West, allowing for these inventions, as well as religious, philosophical, and other cultural values, to be transmitted between different civilizations.

Their fall was inevitable as the empire had grown too large for the central government, as it had been formed, to govern effectively. Adding to this problem was the poor character of the later Han emperors who forgot their duty to the people and saw them only as a means to fund lavish lifestyles instead of their responsibility to care for and protect.

The Period of the Three Kingdoms which followed the Han Dynasty's fall was a time of violence and uncertainty equal in suffering to the Warring States Period. The stability and unity of the Han Dynasty would only be restored many years later by the Sui Dynasty (589-618 CE) who implemented reforms to protect against the weaknesses which led to the fall of the Han while retaining the aspects which had made the dynasty among the greatest in China's history.