Hanji is the name of the handmade paper produced in ancient Korea from the 1st century BCE. Made from mulberry trees its exceptional quality made it a successful export, and it was widely used not only for writing but also interior walls and everyday objects such as fans and umbrellas. Hanji, famed throughout Asia for its whiteness, texture, and strength, is still made today in specialised Korean workshops.

Origins & Success

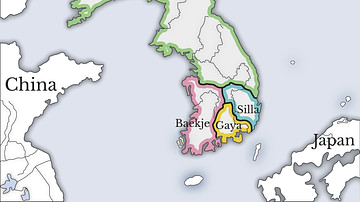

Paper was introduced to Korea from China at the time of the Chinese commandery at Lelang in the 1st century BCE. It was then manufactured throughout the subsequent Three Kingdoms Period. By the 7th century CE and the early years of the Unified Silla Period, the Koreans had mastered the art of manufacturing extremely fine quality paper. Korean-made inks were exported to the Tang Dynasty of China (618 – 906 CE), and such was the growing reputation of hanji that it too was exported to China during the Korean Goryeo Period (918-1392 CE). The Mongolian Yuan Dynasty (13th-14th century CE) were also particularly keen on it to print their Buddhist texts. Just as they had with celadon ceramics, the Koreans had outdone their tutors.

Manufacture & Uses

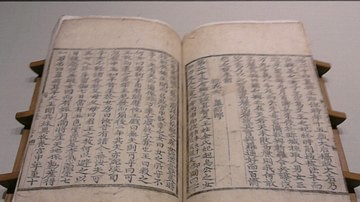

Initially Korean paper was made using hemp fibre, but the highest quality hanji was, for many centuries, made only from the pith of mulberry trees (tak in Korean, Latin: Broussonetia papyrifera). The toughness of hanji meant that it was ideally suited for use in printing presses that used blocks made from magnolia wood which had been soaked and boiled in saltwater and then dried for several years before use. Each block was 24 x 4 x 64 cm and carried 23 lines of vertical text on each side. These were then covered in ink and paper pressed against them. The resilience of hanji was especially useful from the 12th century CE when printing was done using heavier moveable metal type made of bronze, a Korean invention.

In the Joseon Period (from the 15th century CE), such was the demand for hanji, that Sejong the Great (r. 1418 - 1450 CE) permitted other plant materials to be used in its manufacture, especially bamboo. The paper was made in specialised workshops in the capital and the five provincial capitals. The hanji which was produced for state use was supervised by a government agency, the Chonjo-chang.

Another important use of paper was in the interior walls and doors, and sometimes windows, of traditional Korean houses (hanok). The paper was transparent enough to admit a soft light into the home but could also help maintain a cool interior in summer and keep in warmth during winter. In the typical feature of Korean architecture known as ondol, the traditional underfloor heating system, paper was used to cover the stones of the flooring.

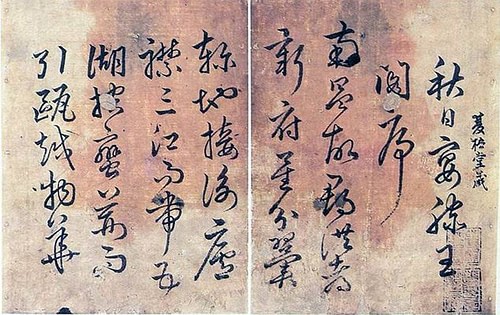

Hand-held paper fans (punchae or buchae) were widely used in ancient Korea by men and women. The first fans were made from leaves, as indicated by the names still in later use for some of the 70-odd known types (e.g. 'banana-leaf' and 'lotus leaf'). They are broadly divided into two types: spatula with a single handle or folding and spread on a split bamboo frame. Both sexes used both types in the home, but in public only men could use the folded type, usually lacquered black. The form, colour and decoration of fans could even indicate a person's social status or dictate their use. For example, folded fans were usually reserved for aristocratic males, at a wedding the bride used a red fan and the groom a blue one, and mourners always used white fans. Fans could be decorated with calligraphy or painted with scenes, the latter being more esteemed when done after the paper had been folded and set onto its frame.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.