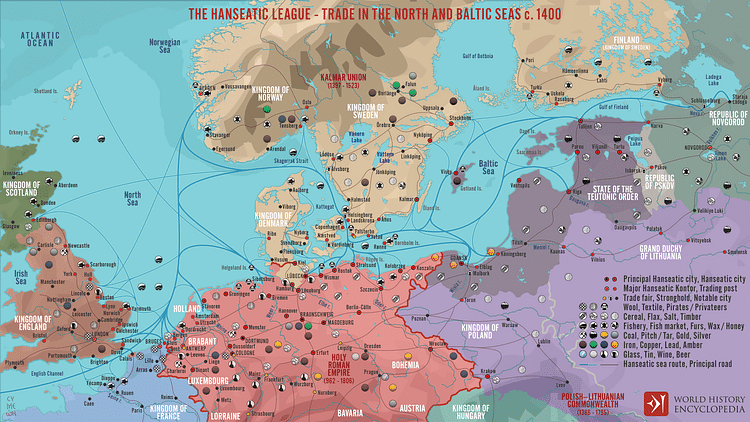

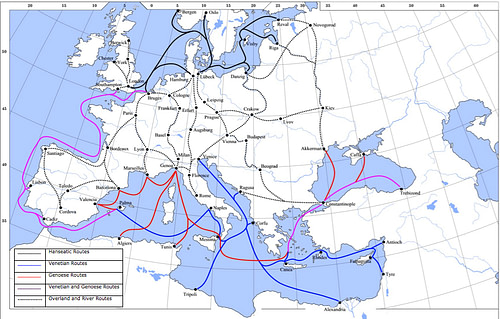

The Hanseatic League (also known as Hansa, Hanse, 1356-1862 CE) was a federation of north German towns and cities formed in the 12th century CE to facilitate trade and protect mutual interests. The league was centered in the German town of Lübeck and included other German principalities which established trade centers ranging from Kievan Rus through the Netherlands, Scandinavia, and Britain.

The league steadily grew in power throughout the 13th century CE and was formally founded as a multi-city trade league in 1356 CE. By the time of its formal founding it had already established a monopoly on trade in the Baltic region through their center on Gotland island in Sweden. From Gotland, the Hanseatic League was able to make firm trade alliances and secure even more lucrative arrangements with other nations.

By setting aside their personal agendas, and working for communal best interests, members of the league were able to make substantial profits until the 15th century CE when their power began to wane. This decline was caused by a number of factors including economic depression, increased power of non-Hanseatic merchants and the nobility which backed them, a depletion of various resources, the plague of the late 14th century CE, and climate change which shortened growing seasons. By the 17th century CE, the league had diminished in numbers and power to be almost inconsequential, and it was dissolved in the 19th century CE.

Establishment of the League

The Hanseatic League grew out of the organization known as the medieval guild. The medieval social paradigm recognized three classes – noble, priest, and peasant – and the feudal system dictated that the noble could charge whatever they pleased in taxes on the peasant class which included merchants and artisans. The medieval guild was formed to protect merchants and craftsmen from bullying and extortion by the upper class. One individual would have little chance standing up to the nobility but an organized group had a much better chance.

The medieval guilds not only protected members but benefited the community. The baker's guild, for example, made sure that all bread was produced according to a certain standard and was priced uniformly. Guilds also provided for the poor, elderly, and orphans in their respective communities and were therefore tolerated by the nobility who were relieved of their “Christian duty” to do the same and could also simply tax a guild master (who drew funds from members) instead of having to track down each individual trader or craftsman.

Lübeck was already an important trade center in the latter part of the 12th century after its restoration by Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Bavaria (r. 1142-1180 CE) in 1159 CE. Like other vital trading towns, Lübeck had its guilds whose members were linked through trade with those of other guilds in various cities. These people most likely shared their stories of difficulties in trade due to excessive taxation, robbery, and the dangers of maritime trade generally, and at some point in the late 12th century CE, these guilds decided to unite as a hansa (a fleet) to pool their resources, protect each other, and increase their profits.

Early Years

Precisely how early the league was formed is unknown but it was most likely during the reign of Henry the Lion, who mandated laws for the protection of foreign traders in the Baltic region, specifically those from Gotland. Henry's laws encouraged freer trade but may have also threatened the security of the merchants of northern Germany. Whenever the league first formed, it was already in operation by 1241 CE, when Hamburg and Lübeck formed an official partnership which monopolized trade in salt and fish. Other city's guilds joined with them in the years between 1241-1282 CE.

Prior to the rise of the Hanseatic League, the nobility and the church held so much power that the merchant class was essentially at their mercy and their economic status was little better than a land-locked serf. The league was powerful enough to challenge the social structure by establishing Kontors (counting houses or offices) in cities ranging from Bruges to London to Novgorod and beyond; all of which brought them incredible wealth. Scholar Norman Cantor comments:

One of the fundamental facts of the thirteenth-century civilization was the failure of the industrial and commercial classes to make use of their economic and intellectual importance to achieve a measure of political leadership in society…the largest class in medieval society, comprising certainly a majority of the total population, was mute. (472)

Even so, the league was able to give a voice to the merchant class by way of a language understood by all: financial success. Cities and towns continued to apply for membership in the alliance first formed between Lübeck and Hamburg until 1356 CE when the Hanseatic League was officially founded. Members swore to abide by the Lübeck Law which stipulated that each would protect and defend another in the league, placing their personal armies at each other's disposal. The league at this time had approximately 80 members but would steadily grow in numbers and power afterwards.

The League at its Height

The league provided much-needed protection for its members not only from hostile political rivals but from robbery by thieves on land or at sea. Crime in the middle ages was rampant owing to the various governments' inability – or unwillingness – to apprehend and prosecute criminals. Scholar Carolly Erikson writes:

In their recurring crises, the fragile governments of the middle ages were quick to lose the power of legal retribution they built up in times of stability. In these periods, the pursuit of criminals and their trying and sentencing were all but suspended; the present impact of the king's justice lapsed, and those who lived outside the law grew in numbers and ambition. (Nardo, 110)

A large aspect of this problem was the monarchy's penchant for pardoning criminals they found useful in furthering their own agendas. Ericson notes how “no road or public place was secure from those who `rode armed publicly and secretly in manner of war by day and night'. Roads were ordered cleared of hedges for 200 feet on either side to prevent ambushes” (Nardo, 107-108). Even so, all an outlaw had to do was to prove himself and his band useful to a local noble, or the king, to receive a pardon and be welcomed into service. The league addressed this situation by forming their own military guards to protect their interests in land travel and made sure that heavily armed transports accompanied their vessels on sea voyages.

The members of the league traded in copper, fish, flax, furs, grain, honey, iron, resin, salt, and textiles, among other goods. Lübeck – the so-called “Queen of the Hanseatic League” – continued as the lead city and amassed considerable wealth. Free cities (such as Lübeck) were obligated only to the Holy Roman Empire which had conferred their status as such and so owed nothing to local authorities of cities outside the league that might object to their ambitions.

Probably the best example of the league's power is its nine-year war with King Waldemar IV of Denmark (r. 1340-1375 CE) and his ally and son-in-law Haakon VI of Norway (r. 1343-1380 CE). The league was powerful enough to wage war on Denmark in 1361-1370 CE, emerging victorious and able to dictate terms which gave them free reign in trade throughout Scandinavia. Further military conflicts with Denmark afterwards only consolidated their power. Cantor sums up the league at its height:

The most outstanding group of independent communes were the German Baltic commercial cities that made up the Hanseatic League. The north German merchants not only engaged in far-flung trade stretching from Russia to England, but they formed political and military alliances and fought Scandinavian kings for hegemony in the Baltic. (471-472)

The league maintained order by meetings held in Lübeck to discuss business and strategize. The various member-cities were not obligated to attend and do not even seem to have been bound by the directions decided upon at these meetings. As long as a member was in good standing and did not pose any form of resistance to the other members, that city or town seems to have been able to do as it pleased.

Even so, as the league grew ever more powerful, some members grew jealous of the success of others and, at the same time, the league's political clout and ability to finance rival ambitions to the thrones of nations began to trouble some of the monarchs. By the 15th century CE, the league was unwelcome in Russia and lost all trading privileges when their offices were closed by Ivan the Great (r. 1462-1505 CE) in 1494 CE. Other nations would follow suit citing the league's tendency to marginalize their own merchants and minimize the profits of non-league traders.

Waning Power

As the league was being shut out of its international markets, Europe, on the whole, was suffering an economic depression which was only getting worse. The Black Death of 1348-1349 CE had killed almost half the population of Europe resulting in a severe labor shortage which affected harvesting crops, transporting goods, and every other aspect associated with trade. Cantor writes:

The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were a period of crisis and dissolution. Plagues and wars were more frequent and more severe and an exhausted and demoralized society did not easily recover from the repeated blows it received. (481)

The Hanseatic League was also finding it difficult to recover its former status and power. Resources which they depended on were no longer available in the same quantity. Cantor notes one example, citing the loss of silver:

In some cases, resources that had been discovered at the height of expansion merely dried up, leaving a gap that the medieval world with its limited techniques could not fill. The supply of new metal, especially silver – the base metal of exchange in northern Europe – was drastically curtailed by the petering out of the rich silver mines in the north. The Goslar mines in Saxony filled with water and there were no technological means of overcoming this difficulty. (482)

The “little ice age” of the 15th century CE also contributed to the league's decline since not only were there fewer people to harvest and transport crops there were fewer crops due to a shorter growing season. What crops there were, furthermore, seem to have been of poor quality. The herring trade, which had been one of the league's early monopolies, was lost to the Netherland merchants because climate change caused the fish to change their spawning patterns, bringing them closer in proximity to Holland and non-league merchants.

The jealousy of some members of the league toward others also encouraged the league's decline. Bruges, for example, became part of the Duchy of Burgundy and challenged Lübeck and the league for markets and so did Holland and others. At this same time, the power of the European nobility – which had been weakened by the deaths of so many serfs in the plague – was in disorder, forced to hire mercenary bands to protect estates and other land holdings. These nobles gladly backed any mercantile enterprise which could bring them the most profit and the league had a long-standing reputation for keeping such profits for themselves.

Conclusion

The time of the league had passed and it continued to decline throughout the 15th century CE as more and more members left and the power of local nobility grew stronger. Throughout the 16th century CE, the league tried to reassert itself and reform, but it was now working within a different political and social paradigm and none of its strategies were effective. The Thirty Years' War (1618-1648 CE) hastened the league's decline in the 17th century, and when the league met in Lübeck in 1669 CE there were less than ten cities represented. The Hanseatic League was effectively ended even though it continued on in name.

Of the nearly 200 cities and towns which once made up the league, only a handful remained and only three – Lübeck, Hamburg, and Bremen – continued to honor the original alliance through the 19th century CE. The Hanseatic League was formally disbanded in 1862 CE.

The memory and mission of the league lives on, however, in the New Hanseatic League which grew from a “new hanse” initiative in 1980 CE to its founding in 2018 CE and presently has 192 members in 16 different countries. The Stadtebund Die Hanse website, providing the history of the Hanseatic League as well as reports on the vision and activities of present members, is overseen by the Hanseburo der Hanse which continues the rich tradition of the Hanseatic League today from its traditional queen city of Lübeck, Germany.