Harold Godwinson (also spelt Godwineson) reigned briefly as King Harold II of England from January to October 1066 CE, the momentous year which witnessed the Norman conquest and end of 500 years of Anglo-Saxon rule. Harold had been, as the Earl of Wessex, the most powerful man in England prior to his taking the throne, and his military accomplishments included successful campaigns in Wales in 1063-4 CE and victory over an invading army led by Harold Hardrada, king of Norway in September 1066 CE. In October 1066 CE Harold was killed and his army defeated at the Battle of Hastings, the first stage in William the Conqueror's dramatic takeover of England.

Earl of Wessex

Harold was born around 1023 CE into the powerful Godwinson family, with his father, Godwin, being the Earl of Wessex and one of the richest men in England. Harold's mother was Gytha of the Thorgils family, and she, through her brother Ulaf, was connected to the royal house of Denmark. In 1045 CE Harold was made the earl of East Anglia, then a part of his father's huge estates. On the death of his father, Harold became Earl of Wessex in 1053 CE and, despite having to give up East Anglia in order for the king, Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066 CE), to have a more balanced distribution of power amongst his earls, he became one of, perhaps the most powerful man in England. The 1050s CE had seen the Godwines in a bitter rivalry with the king, which at one point saw Harold temporarily seek refuge in Ireland (1051-2 CE). This rivalry was despite Edward having tied himself to the Godwines by marriage - wedding Edith, the daughter of Godwin in 1045 CE. The Godwines proved too powerful and their followers too loyal for the king to sideline for any length of time, though. In addition, Harold proved himself a useful leader for the king, building his reputation on such successful military conquests as the attack on Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, King of Wales in 1063-4 CE.

Harold was assisted by his brother Tostig, Earl of Northumbria in Wales, and the two earls launched a land and sea attack in the autumn of 1063 CE, driving Gruffydd into forced exile. The Welsh were so concerned at Harold's threat that they caught up with their king, killed him, and presented his head to the Earl of Wessex. Harold gained great credit from the campaign and was widely applauded as the subregulus (under-king) and dux Anglorum (commander-in-chief of the English).

Harold's next success came when he sorted out the problems in the north of England caused by his brother Tostig whose harsh rule and overtaxation had caused a serious revolt in Northumbria in 1065 CE. Tostig was ultimately stripped of his title and banished out of harm's way to Flanders while Harold managed to placate the Northumbrian nobles by visiting the area in person. There were rumours, however, that Harold had engineered the whole episode in order to gain even greater favour with King Edward and promote himself as the king's chosen heir.

Harold was also busy in his private life c. 1065 CE, marrying Ealdgyth, former wife of Gruffydd, in what was likely a union intended to cement both loyalties in Wales and, because she was the sister of the earls of Northumbria and Mercia, also in northern England. Harold, in addition, had a long-term partner, Edith Swan-Neck, with whom he had five children.

Harold in Normandy

Harold Godwinson's star rose even higher when he was crowned king on 6 January 1066 CE following the death the day before of his brother-in-law King Edward the Confessor, who died childless. Harold had acquired the crown in unclear circumstances, although Edward, on his deathbed, had personally nominated Harold as his successor and, in truth, there were not many other viable candidates. One possible claimant was Edgar Ætheling, son of Edward the Exile (d. 1057 CE) and the great-nephew of Edward the Confessor, but he was only in his early teens in 1066 CE and so he was sidelined by Harold, likely with the support of the other English earls (although the whole affair remains mysterious for lack of unambiguous sources). One thing is certain, the rapidity with which Harold had himself crowned was unprecedented and smacked of getting the deed done before too much argument broke out amongst rival claimants.

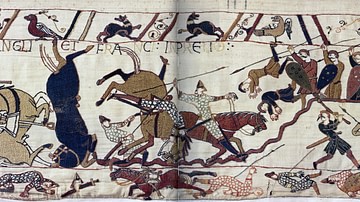

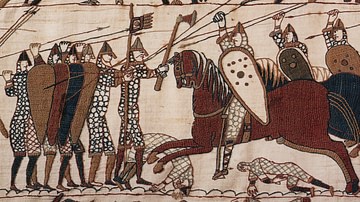

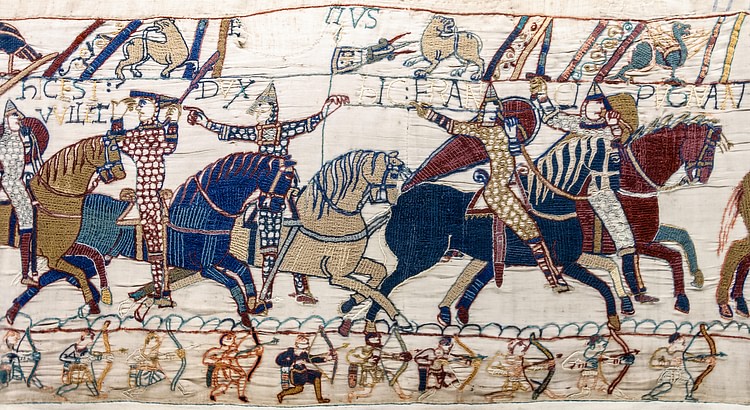

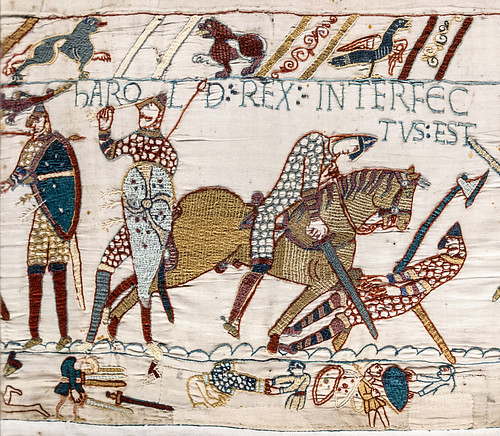

These were the events of early 1066 CE but the full story, pertinent to the dramatic events of later in the year, requires going back to two years earlier, in the spring of 1064 CE. Then, Harold was (possibly) sent on an unknown mission by Edward to the court of William, Duke of Normandy. The purpose may have been to inform William that he was the nominated successor to the English throne and pledge his loyalty to the Norman duke. Certainly, William would later claim that Edward had made such a promise back in 1051 CE (when the Godwines were in the royal doghouse, so to speak). In alternative versions of events, Harold never went to Normandy at all or was merely blown off course and landed in France by accident. The English earl was then captured by Count Guy of Ponthieu and released only thanks to a payment from William, who then hosted Harold in his own court (or kept him a prisoner). William put Harold to good use in the Normans' battles with Duke Conan of Brittany where Harold fought bravely and earned the respect of his 'captors'. Scenes from this escapade - including an episode where Harold saves Norman warriors sinking in the quicksands around Mont-Saint-Michel - and the following battle at Hastings, are vividly depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, made between 1067 and 1079 CE.

Harold was knighted by William for his efforts - if the Bayeux Tapestry is to be taken literally - and it was perhaps a condition of Harold's release from William's grasp that he had to promise William the throne of England or at least accept vassal status. That, at least, is the version presented by Norman chroniclers such as William of Poitiers who adds that Harold also promised to act as William's agent in England and refortify Dover castle in readiness for a Norman garrison to take it over.

Another take on events, presented in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, states that Harold only visited William's court to secure the release of a number of captured compatriots. To add another layer of interpretation on these murky happenings, the pro-Anglo-Saxon camp suggested that even if Harold did make a pledge of loyalty to William then, being at the time a captive, it was done under duress and so invalid. Whatever the real situation of promises, diplomacy and rival claims, William was prepared to use force to wrest the crown from Harold's head and take England for the Normans.

Battle of Stamford Bridge

The most immediate threat to Harold's kingdom was not from William, though, but from the north and another rival claimant to the throne, Harald Hardrada, king of Norway (aka Harold III, r. 1046-1066 CE). Hardrada believed he was the rightful ruler of Denmark, a kingdom which had long-claimed sovereignty over large parts of England and which had been, since 950 CE, receiving regular payments from English kings in order not to invade. Hardrada's secondhand claim was more than a little dubious as he had already failed in his attempt to take the Danish throne for himself. A second and just as dubious claim to the English throne came from Hardrada's inheritance from his own predecessor, Sweyn (Swein) of Norway, who was an illegitimate son of Aelfgifu, wife of King Cnut (aka Canute), the king of England from 1016 to 1035 CE. Like William, Hardrada was prepared to press his claim through force, and he amassed an invasion fleet which sailed to England in September 1066 CE.

Hardrada's fleet numbered around 300 ships and his army around 12,000 men. He was usefully assisted, too, by Tostig, the ex-Earl of Northumbria, who saw Hardrada as the ticket to wresting the throne from his brother. Hardrada's fleet arrived off the north-east coast of England near the mouth of the River Tyne on 8 September where it was joined by a small fleet of perhaps 12 ships commanded by Tostig. From there the two fleets sailed south and eventually landed at Ricall, just 16 km (10 miles) from the key city of York. The first battle was at Fulford Gate, an uncertain location somewhere near York. There, on 20 September, an Anglo-Saxon army led by Eadwine, earl of Mercia, and Morcar, the earl of Northumbria, clashed with Hardrada's army. The king of Norway was victorious, but Harold was already on his way north with a second army which included his elite force of up to 3,000 housecarls (aka huscarls, professional armoured troops).

Battle of Hastings

Throughout the summer of 1066 CE William had been busy amassing a fleet on the northern coast of France near Saint-Valéry-sur-Somme. A contemporary Norman source puts the total number of ships at 776, but this is likely an exaggeration. The Norman warriors were motivated by the promise of booty and lands in the conquered territory but they were also paid by William during the summer preparation period. The total force is unknown, but most historians suggest a figure of 5-8,000 men, which included 1-2,000 cavalry.

On 28 September 1066 CE, William and his invasion army landed at Pevensey in Sussex, southern England, where there was a good harbour and the added advantage of an old Roman fort which, refortified by William, provided some protection for the army's camp. Then news came of Harold's victory at Stamford Bridge and that he was marching south. Harold arrived in London on 6 October and mustered his army, gathering at Caldebec Hill, 13 km (8 miles) north of Hastings, on the 13th.

Harold's force included his elite housecarls and the general levy or fyrd, less well-trained troops supplied by each shire of the kingdom. Given the closeness of the coming battle, it seems likely that the armies of defenders and invaders were more or less equal in size. One persistent criticism from medieval writers is that Harold mobilised too soon, perhaps deliberately enticed to do so by William's orders to ravage the territories of the south-east coast, Harold's personal estates.

The two armies met on 14 October 1066 CE. Harold's army took up position on a low rise, 'hammer-head ridge', which was protected on the sides by woods and in front by a stream and marshy ground. The Anglo-Saxons, mostly on foot, formed a 'shield-wall' and, bristling with spears, axes, and swords, they prepared to face the enemy. William's forces took up position to the south of the ridge in three infantry divisions: (from the left) Bretons, Normans, and French, all with a line of archers and a number of crossbowmen in front and the cavalry held in reserve at the rear. It seems that the Anglo-Saxons had only a few archers at the Battle of Hastings and no cavalry.

The Normans first launched a barrage of arrows, with the Anglo-Saxons responding by hurling a hail of stone axes at the enemy infantry as it tried to climb the ridge. The Norman cavalry was then sent in but was hampered by the terrain and slope so that they, too, were repelled by the Saxon shield wall. At one dramatic moment, a cry went up amongst the Normans that William had been struck down. This could have turned the battle as many an army in the Middle Ages had deserted the field once their commander had fallen. William, however, was unhurt, and he raised his visor and rode amongst his men to show that he was still alive and in command of the situation.

A number of the Anglo-Saxons, encouraged by the retreat of the Norman cavalry, then raced after them down the hill, but once on lower ground and losing their formation, they were cut down by the Norman horseman as they reverse-charged. Seeing the success of this, William ordered a further two feigned charges and retreats up to the ridge and back again, both times luring the enemy into a pursuit and ending in a successful counter-attack on flatter ground more suitable for the horses.

Death of King Harold

The fighting had now been raging for several hours, an unusually long time for a medieval battle. However, the superiority of the Norman cavalry against the Anglo-Saxon infantry was gradually winning the day, and now that their numbers were reduced, there were not enough Anglo-Saxons to defend the ridge. It was at this point that the depleted number of the best-trained troops, the housecarls (following the Battle at Stamford Bridge), must surely have been a telling factor. In a final cavalry charge, Harold and other Saxon leaders, including the king's brothers Gurth and Leofwine were killed. Harold's death, at least in the prevailing tradition, was caused first by an arrow to the eye, then he was knocked over by a cavalry charge, and finally hacked to pieces by Norman swords as he lay prone on the ground. The contemporary and later sources are, however, all conflicting on exactly how Harold may have died. The remaining Anglo-Saxons fought a valiant rearguard action as they retreated to a nearby hill, the Malfosse, but they were eventually wiped out, and total victory was William's.

William the Conqueror, as he became known, was crowned William I, king of England on Christmas Day of the same year at Westminster Abbey, bringing an end to 500 years of Saxon rule. William, though, did have to struggle for five more years - winning battles against rebels in the north of England and building Norman motte and bailey everywhere - before he completely controlled his new realm.

Harold's Tomb

The fate of Harold's body is unknown. In some versions of the story, his mother Gytha offered her dead son's weight in gold to have the body for decent burial but she was refused by William. In another version, Edith Swan-Neck was called in to help identify the corpse, such was its mutilation. One 12th-century CE tradition states that his remains were removed from burial near the battlefield to Waltham Abbey in Essex - although a later exploration of the tomb revealed that it was empty. There was even a legend that Harold had survived the battle and lived into old age but such stories and the mystery of the fallen king's burial are probably exactly what William wished: there would be no king's burial and no martyr's grave for rebels to rally around - the Normans were here to stay.