The Hawker Hurricane was a single-seat fighter plane, Britain's first monoplane, which fought in the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940. Slower but more numerous than the Supermarine Spitfire, the Hurricane was used by the Royal Air Force in multiple theatres of the Second World War (1939-45).

The versatile plane gained particular renown for its ability to destroy enemy armour on the ground using cannons, bombs, and rockets. Known for its reliability, many other allied air forces flew Hurricanes during the war, and a version was deployed by the Royal Navy, the Hawker Sea Hurricane.

Design

In the pre-war years, the British Air Ministry wanted a fast and modern fighter plane that could rival the Messerschmitt Bf 109 (Me 109), which became operational in the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) in 1937. The Me 109 had already caused a stir that summer by setting several speed records. The Hurricane was built by Hawker, well-established as the maker of Sopwith planes, and was designed by the company's talented chief designer Sydney Camm (1893-1966). The Hurricane was a radical break from the biplane designs which had hitherto dominated British military aircraft. It was the RAF's first single-wing fighter plane and was reliable, highly manoeuvrable, and most of all fast, in fact, at least 100 mph (160 km/h) faster than any previous British plane. Initially built around a Rolls-Royce Goshawk engine, the designers soon switched to the more powerful and reliable Rolls-Royce V12 Merlin engine, the same engine that would power such iconic aircraft as the Spitfire, Lancaster bomber, and P-51 Mustang. Rolls-Royce Merlin engines were remarkably reliable thanks to their design and the practice of testing parts until destruction, particularly when adding innovations, a continuous process throughout the war.

The first Hurricane prototype was flown on 6 November 1935 with the aircraft undergoing trials in February 1936. The Air Ministry was pleased with the results, particularly the speeds attained, and so it made an order for 600 planes the following June. The first Hurricane production aircraft was flown on 12 October 1937. The Hurricane first entered RAF service in December 1937 with No. 111 Squadron based at Northolt, West London.

The aviation historian D. C. Dildy gives the following assessment of the Hurricane:

A robust, stable, retractable-gear monoplane, the Hurricane was built using outdated mixed construction methods, which made it relatively heavy but permitted high production rates for the expanding Fighter Command. (30)

By the close of 1938, as war loomed over Europe, the RAF had around 200 operational Hurricane fighters. With a conflict looking ever more certain, another production plant became involved besides Hawker, Hucclecote of the Gloster Aircraft Company. Significant design improvements were made in the early years, such as switching from a two- to three-bladed propellor (which improved handling and operational altitude), making the windscreen bulletproof, adding an armoured plate to protect the pilot's back, and replacing the fabric-covered wings with thin metal. The plane attracted other buyers, and so Hurricanes were supplied, sometimes through licensed factories, to air forces in Australia, Belgium, Canada, India, Iran, Poland, Romania, Turkey, the USSR, and Yugoslavia, amongst others.

By the time Germany invaded Poland in September 1939 and war was declared, the RAF had 18 Hurricane squadrons. Four of these squadrons were relocated to northern France in anticipation of a German land attack. Another six squadrons followed, but it was too little too late as the might of the Luftwaffe and German armoured land forces swept across Western Europe. 396 Hurricanes and 80 fighter pilots were lost in the debacle that became known as the Fall of France. The RAF's fighter capability was worn down to 331 planes. More fighters, both machines and men, were desperately needed for the coming defence of Britain.

Specifications & Armament

As with many other successful aircraft on both sides, the Hurricane was continuously developed in the never-ending race to achieve superiority in the air. The Hurricane had a length of 32 feet 2.5 inches (9.82 m) and a wingspan of 40 feet (12.19 m). Most Hurricanes were fitted with a Rolls-Royce XX Merlin engine capable of 1,280 hp (954 kW). The maximum speed at 22,000 ft (6,705 m) was around 340 mph (550 km/h). The plane could operate effectively up to a ceiling of 36,500 ft (11,125 m). The usual range was 480 to 600 miles (772 to 965 km), depending on the model, unless fitted with extra fuel tanks, which allowed for a range of 985 miles (1,585 km).

The first Hurricanes were fitted with 8 Browning machine guns of 0.303 (7.7 mm) calibre, four in each wing. Each machine gun had 332 rounds, and so they could be fired for a total of 17 seconds. Later Hurricanes had 12 machine guns. Alternative armament included replacing the machine guns with four 0.8-inch (20 mm) cannons. In the second half of the war, the Hurricane was reimagined as a fighter-bomber that could attack armour on the ground. Accordingly, the plane could be fitted with a single 500-lb (227 kg) bomb or two bombs weighing 250 lb (133 kg) each. In the same vein, the Hurricane was the first Allied plane to be fitted with air-to-ground rockets, used in action for the first time on 3 September 1943. Each rocket had a 60-lb (27 kg) warhead. Another armament alternative was to have two 1.5-inch (40 mm) cannons instead of the smaller cannons or machine guns, although each of these cannons had a 0.303 machine gun fitted right alongside to help with aiming. The 40-mm cannons certainly packed a punch and gave the reinvented Hurricane a new nickname, the 'tank buster'.

Over 14,500 hurricanes were built. Camouflage colours included dark green and brown or dark green and grey for Europe, dark brown and yellow for North Africa, or even black for night fighter duties.

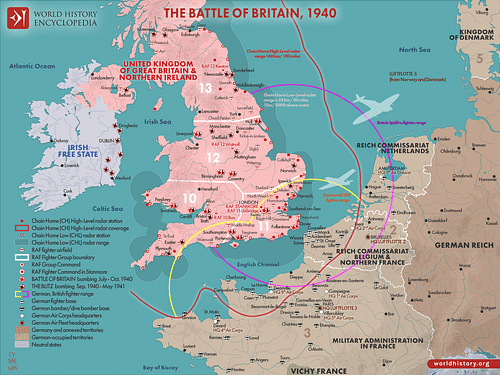

Battle of Britain

Fortunately for Britain, the German leader Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) inexplicably delayed the prelude to the planned invasion of Britain (Operation Sea Lion), which was for the Luftwaffe to gain air superiority over the English Channel. These precious few months of breathing space were frantically spent building aircraft and training pilots for the battle that became known as the Battle of Britain, officially dated as 10 July to 31 October 1940 by the Air Ministry. The RAF could put into the air 32 squadrons of Hurricanes and 19 squadrons of Spitfires. The Spitfires were faster and more manoeuvrable, but the sheer numbers of the Hurricanes made them crucial to meeting the Luftwaffe threat.

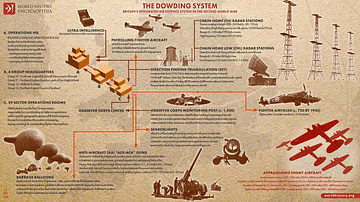

Home advantage was an important factor in the battle since the German fighters had far less time in the skies above Britain before their fuel ran out. Another advantage was that German pilots obliged to bail out and use their parachutes, if they survived, became prisoners of war. This was a battle where men were just as vital as machines, and training pilots and replacing losses became problematic for both sides. Another British advantage was radar, which communicated to fighter squadrons approximately when and where German planes were flying. The Observer Corps, a volunteer group, took over from radar when the planes passed the electronic listening stations. The Luftwaffe could attack from bases across the Channel and in Scandinavia. It was also true that because it took the British fighters up to 20 minutes to assemble and reach the necessary altitude, the German escort fighters were often ready and waiting for them. The battle would be finely balanced with both sides never entirely sure of their enemy's losses.

As the Spitfire was better matched against the Me 109, Hurricanes were often directed to attack the slower Messerschmitt Bf 110 (Me 110) fighter-bomber and various types of heavier bombers when a choice was possible. That was at least the theory and was specified as such in this directive from Air Vice Marshal Keith Park:

READINESS SQUADRONS: Despatch in pairs to engage the first wave of the enemy. Spitfires against the fighter screen, and Hurricanes against bombers and close escort.

(Saunders, 41)

However, this was not always possible in reality, and the false idea that Spitfires always took on fighters while Hurricanes took on bombers is remarked on here by Squadron Leader Anthony Norman, Sector Controller at RAF Kenley during the Battle of Britain:

It is important to emphasise that it was never the case the Hurricanes were specifically dispatched to deal with the bombers and the Spitfires to engage the fighters, although it is often suggested that this is what happened. That notion is complete rubbish because it was impossible, tactically, as we just didn't know, anyway, how the raid being intercepted was made up. We had no way of knowing if it comprised fighters, or bombers, or both. So, at Kenley we could end up sending No. 615 Sqn's Hurricanes against fighters and then No. 64 Sqn's Spitfires after a bunch of bombers. It had to be that way.

(Saunders, 39-41)

When the Luftwaffe began to use armour plating in its planes, the RAF began to use more cannons in its own planes. In the latter stages of the Battle of Britain, Spitfires and Hurricanes were used as a single tactical unit of 60 aircraft, a formation known as a 'Big Wing'. These fighters, as all fighters, were ordered to prioritise hitting the bombers when possible.

The Germans kept the British guessing by continuously switching targets, such as Channel shipping, coastal towns, airfields, radar stations, and London. In the end, RAF fighter pilots, who included many from the Empire nations and allies such as Poland and France, fought off the Luftwaffe threat, whose losses became unsustainable. The RAF's total aircraft losses were around 788, compared to the Luftwaffe's 1,294 (Dear, 127).

By October, the Germans had changed strategy again and focussed on the nighttime bombing of cities, a heavy blow for civilians but strategically a much less important target. The RAF had won the Battle of Britain, and Operation Sea Lion was abandoned. The glamorous Spitfire might have grabbed the headlines, but in the battle, "Hurricanes destroyed more enemy aircraft than all other defences, air or ground, combined" (Mondey, 152). Going into 1941, the RAF now had 32 Hurricane squadrons it could put to new purposes in new places.

Other Theatres of War

Britain had much territory to defend, and so Hurricanes were deployed in many other theatres of the war. Even at the height of the Battle of Britain, three Hurricane squadrons were spared for use in Malta and the Western Desert. Hurricanes were used to escort bombers, engage enemy fighters, or attack ground targets. It was in North Africa that the Hurricane first displayed its effectiveness against enemy armour on the ground, destroying tanks and armoured vehicles with its rockets or heavy cannons.

Eventually, Hurricanes were used as far afield as Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and Burma (Myanmar). There was, too, a naval version, the Hawker Sea Hurricane, which was used in the defence of the Atlantic convoys which brought vital supplies of all kinds from North America to Britain. Early versions of the Sea Hurricane were launched by catapult from naval and merchant ships (but the pilot was obliged to then ditch since there was no way to land back on the vessel). Later versions operated from conventional aircraft carriers. The Sea Hurricane was employed by both the Royal Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy.

End of Service

In the second half of the war, the Hurricane was often replaced by the faster and more manoeuvrable Hawker Typhoon fighter-bomber, which excelled when operating at high speed and at low altitude, and, from 1944, the Hawker Tempest. The last Hurricanes to serve in the RAF were finally replaced in January 1947. For its distinguished service in the Battle of Britain, a Hurricane is usually selected to lead official RAF commemorative flyovers.