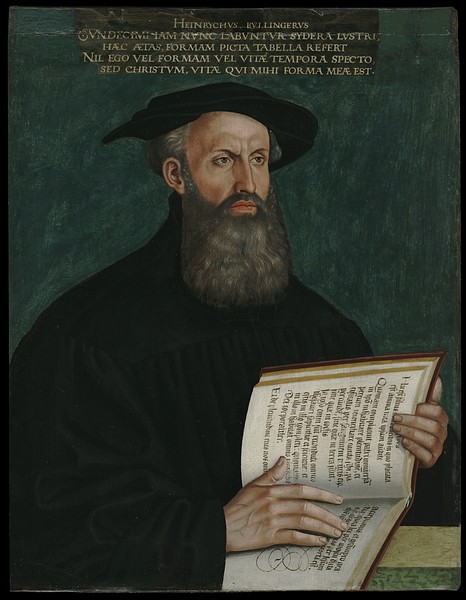

Heinrich Bullinger (l. 1504-1575) was a Swiss reformer, minister, and historian who succeeded Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) as leader of the Reformed Church in Switzerland and became the theological bridge between Zwingli's work and that of reformer John Calvin (l. 1509-1564). He is best known for his Helvetic Confessions, which influenced those of other Protestant sects.

Bullinger was studying to become a Catholic priest when he was introduced to the works of Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) and embraced the Protestant vision. He then heard Zwingli preach and moved from Lutheranism to Zwingli's interpretation of Christianity. Zwingli's radical approach to Catholic conversion resulted in the Kappel Wars in which he was killed in battle in 1531. Bullinger then assumed Zwingli's position as pastor of the Grossmünster (Great Church) in Zürich.

Recognizing that Zwingli's politicization of Christianity had inspired the war that cost Zürich 500 of its citizens, Bullinger agreed with the city council to keep politics out of his preaching and focus only on the scriptures. He carefully supervised all of the churches he was responsible for while also overseeing educational programs, writing theological and historical works, and corresponding with several monarchs and other reformers on religious matters.

He is considered the originator of the concept of covenant theology later popularized by Calvin, with whom he corresponded regularly and whose teachings he influenced. Although not as well-known as figures like Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin, Bullinger played just as significant a role in the Protestant Reformation by preserving Zwingli's initial vision of justification by faith and the Bible as the sole spiritual authority until it could be fully developed by Calvin, whose works then influenced the establishment of later Protestant churches.

Education & Conversion

Bullinger was born on 18 July 1504 in the town of Bremgarten, Switzerland, to Heinrich Bullinger and his common-law wife Anna Wiederkehr. Heinrich senior was the parish priest and, as such, was not supposed to marry but, like many priests throughout Europe, got around the Church's policy against clerical marriage by paying his bishop a yearly fee. Young Heinrich was the fifth child of this marriage, and his father encouraged him to pursue the priesthood from an early age, teaching him at home. When he was twelve, he was sent to school in Emmerich where he was introduced to the scholastic theologians whose work informed clerical training, notably Augustine of Hippo (l. 354-430), Thomas Aquinas (l. 1225-1274), and John Duns Scotus (l. c. 1265-1308). He was recognized as a scholar of remarkable ability and encouraged to continue his education.

He was only 14 years old in 1519 when he entered the University of Cologne, where he read the works of the humanist theologian, philosopher, and priest Desiderius Erasmus (l. 1466-1536) as well as those of Martin Luther and Philip Melanchthon (l. 1497-1560). Luther had been condemned as a heretic and outlaw after the Diet of Worms in 1521 and, at the time Bullinger was studying at Cologne, citizens were burning Luther's books in accordance with the Church's decree.

The Church's reaction to Luther's teachings only encouraged Bullinger's interest, and he read them along with Melanchthon's famous treatise Loci Communes, which caused him to rethink his devotion to the Catholic Church and embrace the Reformed movement of the Lutherans. Encouraged by this new vision, he read the Bible for himself and became convinced of Luther's claim that one was justified by God through faith in Christ alone, not by the precepts of the Church or one's own works.

He graduated from university in 1522, and in 1523, he became the headmaster at the Kappel Abbey in Kappel am Albis. He rejected the Church's educational program, which taught memorization of liturgy and ignored the Bible, and instituted Bible study and interpretation. He was open with the authorities regarding his beliefs and his new policies, and these seem to have met with his immediate superiors' approval as he remained in his position from 1523 to 1529, and during that time, he elevated biblical literacy above liturgy and changed worship services from the Catholic Mass to the Reformed Protestant service.

Zwingli & Return Home

In 1527, he traveled to Zürich and heard Zwingli and his co-reformer Leo Judd (l. 1482-1542) preach. He was instantly drawn to Zwingli's vision, which, like Luther's, emphasized faith alone and Christ alone as the means to salvation. Zwingli also preached the Bible as the sole authority in secular matters and advocated for a united Protestant Switzerland modeled on the community of early Christianity depicted in the Book of Acts. This concept appealed to Bullinger, who conferred privately with Zwingli and later accompanied him to the Disputation in Bern in 1528.

That same year, Bullinger took on a part-time position in the village of Hausen, near Kappel am Albis, where he began to preach the Reformed vision in June. While the young Bullinger had been moving toward Reformed Christianity, however, his father had been on this same path and declared himself an evangelical proponent in 1529. He was forced to resign as parish priest, and Bullinger left his position in Kappel to return home and assume the post. His father had been forced out by parishioners who rejected the Reformation, but when Bullinger arrived, he was welcomed, even though he preached the same vision and, in fact, a far more radical version of his father's convictions.

Bullinger's sermons against the veneration of icons encouraged the people of Bremgarten to destroy them, breaking stained glass windows, and burning images and statuary as symbols of idolatry. Why the people of the village rejected his father's Protestantism and embraced his own is unclear, but one aspect of Bullinger's character noted by others was warmth and compassion that drew people to him.

Kappel Wars & the Grossmünster

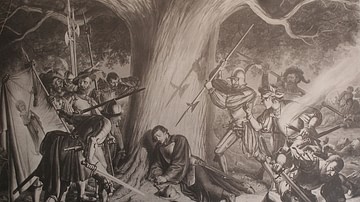

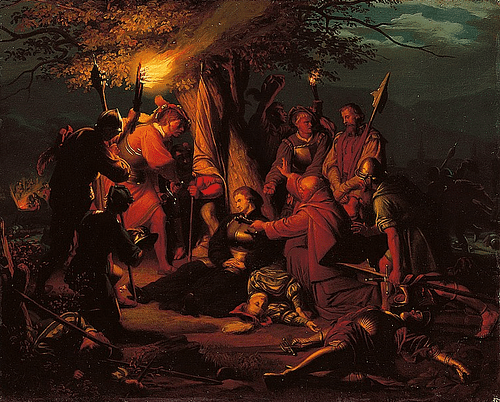

Bullinger was in Bremgarten when Zwingli called for the forcible conversion of the Catholic cantons (provinces) in 1529, initiating the First Kappel War. Hostilities were averted by a Protestant delegation from Bern, while the armies were already mobilized in the field at Kappel, establishing the Peace of Kappel am Albis. Zwingli accepted the peace terms but continued to call for military action and forced conversions to realize his vision of a united Protestant country.

Unable to win support for an invasion of the Catholic cantons from other Protestant cities, he settled for a blockade, depriving the Catholics of necessary salt, grain, and other necessities. The Catholic cantons responded in October 1531 by marching on Zürich in the Second Kappel War during which Zwingli fell in battle along with 500 others. The Catholics attacked again on 24 October, ending the war and offering terms that allowed Zürich and the other cantons to practice whatever form of Christianity they pleased as long as they left the Catholics alone.

In Zürich, the backlash to the Kappel Wars was swift and Zwingli's movement stalled under criticism of his militancy, politicization of religion, and the deaths of the 500. According to scholar Lyndal Roper, Zwingli had presented the wars as ordained by God and assured his followers that they would triumph in God's name. When the Second Kappel War went badly against Zürich, Roper notes, a fellow citizen yelled at Zwingli:

You told us they would run away, that their bullets would rebound on them...You cooked up this gruel and put the carrots in too – now you must help us eat it. (335)

Afterwards, this sentiment only grew, and Zwingli's movement was endangered as Catholics reasserted their control over regions that had been evangelized by Protestants, while Zwingli's followers in Zürich questioned the precepts they had embraced before Kappel. Bremgarten was reclaimed by the Catholics, and Bullinger and his family – which by 1531 included his wife, Anna Adischwyler, and an infant – fled to Zürich. Bullinger had moderated his views after the destruction his sermons of 1529 had caused and was accepted by the city council as Zwingli's successor to the Grossmünster on 9 December 1531 at the age of 27.

Bullinger the Moderate

Bullinger's first priority was to stabilize the movement thrown off course by Zwingli's political advocacy of military action. Scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch notes:

It was little thanks to Zwingli that his work in Zurich did in fact recover. The city's Reformation was steered back to stability by Heinrich Bullinger, a wise and patient man and a great preacher. (176)

Bullinger agreed with the city council against any politicization of the pulpit and maintained focus on inspirational preaching from the Bible and application of biblical principles to the lives of his parishioners. The city council appointed him antistes (Chief Minister), and in this capacity, he was responsible for many other churches in the region besides the Grossmünster and personally oversaw the conduct of the pastors. He also supervised the educational system of Zürich, maintaining the same high standards he had experienced during his youth at school and emphasizing the importance of biblical literacy.

He and Anna had eleven children and adopted others who had been orphaned. The couple opened their home to anyone in need and frequently took in refugees fleeing from persecution in other regions or nearby Catholic cantons. In addition to his altruistic outreach, his responsibilities as pastor of Grossmünster, and his educational initiatives, he was a prolific writer, corresponding with fellow reformers throughout Europe as well as writing his own original works of theology and history.

Covenant Theology & Famous Works

One of the most important concepts for the later development of Protestant Christianity was Bullinger's covenant theology which claimed God had offered an agreement to humanity which Christians were obligated to honor through obedience to the divine will. Covenant theology defined the human relationship with the divine as a compact – a covenant – whereby the one party provided something of value – the grace of salvation – in return for acknowledgment through grateful devotion and works manifesting that gratitude. There was nothing one could do to earn salvation – it was God's free gift one only had to accept – but one was expected to reflect that gift in one's life through one's works.

Bullinger explored this concept through his famous work Decades. Scholar Frank. N. Magill comments:

The Decades consists of five groups of ten sermons published [between 1549-1551]. The sermons were widely read, and they exerted considerable influence outside of Switzerland, especially in the Church of England, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth, where the sermons were required reading for those studying to be preachers. (382)

The Decades were written in Latin and then translated into English in four volumes in 1577, 1584, and 1587. Among the topics covered were predestination, God's grace, the nature of the divine, the authority of scripture which reveals that nature, and a definition of the true Church as opposed to false teachings. Magill sums up Bullinger's thoughts on this last topic:

The Church of Rome is not the true Church; the latter is inwardly constituted by true believers and is visibly found wherever the Word of God is faithfully preached and the sacraments of baptism and the Lord's Supper are properly administered. (381)

In this, he was addressing the central question of what constitutes Christianity, which in his view – as developed from the teachings of Luther and Zwingli – meant centering one's life on Jesus Christ's ministry as revealed in the Bible and rejecting any practices or policies that distracted from that focus.

In articulating this vision, he hoped to provide a basis both Lutherans, Zwinglians, and others could agree upon, and he developed this further in the Helvetic Confessions, which established a unifying vision of Protestant theology and practice. The First Helvetic Confession (1536) was written by Bullinger and Leo Judd, with contributions by other Protestant theologians, addressing schisms between Lutherans and others over the nature and right observance of the Lord's Supper. The Second Helvetic Confession (1562) was written by Bullinger alone and dealt with Reformed tenets, doctrines, and rituals, presenting a unifying vision of Protestant faith, which attempted to recognize, and synthesize, differences in interpretation.

In addition to these works, he wrote a history of Zürich and contributed to the Consensus Tigurinus (Consensus of Zürich) by John Calvin in 1548, which also attempted to unify differing Protestant sects. At the heart of this document, like with the First Helvetic Confession, was a discussion of the meaning of the Lord's Supper, addressing the Lutheran view (that Christ was present in the ritual) and the Reformed understanding (that the rite was simply a memorial to Christ's sacrifice), and baptism. The document was intended to present a moderate view most could agree on.

Bullinger was also a prolific correspondent, and 12,000 of his letters remain extant, more than any other reformer. Bullinger wrote and carefully preserved his correspondence for publication in order to avoid the kind of misrepresentation he felt Zwingli had suffered after his letters were published posthumously. Scholar Mark Greengrass notes:

Heinrich Bullinger kept his correspondence, thereby providing researchers with the core of what is the largest collection of letters from the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformers – over 12,000 letters. (Rublack, 437)

He also supervised the publication of his letters, and other Protestant works, to ensure the individuals, and the movement generally, was represented accurately.

Calvin & Influence

Although the concept of predestination – that some people are elected by God for salvation and others are not – is generally attributed to Calvin, it was suggested by Luther and developed by Bullinger in his Decades. Predestination is understood in different ways but, generally, maintains that God is in complete control of everything that happens in one's life, based on passages of scripture such as Psalm 139:15-16 which reads:

When my bones were being formed, carefully put together in my mother's womb, when I was growing there in secret, you knew I was there; you saw me before I was born. The days allotted to me had all been recorded in your book, before any of them ever began.

Everyone's life, then, is already charted – right down to the day of one's death – before one is born, and there is nothing an individual can do about that. According to this view, God has a plan, which is only known to the divine will and must be acknowledged as just, in accordance with the nature of God, even if one does not understand it.

Predestination does not absolve one of personal responsibility, however, in that, even if one's life has been written already, one is still expected to honor God through one's decisions and resultant actions because God is all-wise, all-good, and all-knowing. God might have planned that one will be tempted to steal a certain amount of money, for example, but has not ordained how one will respond either to the temptation or to being caught if one gives in, though one's action is already known. When one is caught and punished, it is up to the individual to respond with repentance and continued devotion to understanding the divine will, even if it makes no sense to that person. Bullinger emphasized the saving grace of God available to all; one was only damned if one rejected that grace.

In making this point, he was rejecting the claim that God was the cause of sin or any kind of evil, noting that God was all-good, but that temptations to sin or evil acts were part of God's plan to test one's faith and encourage one to seek His grace either in resisting temptation or repenting of sin once one had fallen. Calvin took this thought and developed his concept of predestination, arguing that God, the source of all things, was like an author whose characters have only as much free will as has been granted to advance the plot.

The exercise of that will comes down to accepting or rejecting the message of salvation based on the story already written for one's life or, in other words, none. Since God is in control, everything one does – good or bad – has been decreed. Calvin rejected free will as a challenge to God's sovereignty. To Calvin, if one is elected to be saved, one should praise God for his goodness; if one is predestined for damnation, one should also praise God for his justice; either way, there is nothing one can do to alter one's fate.

Conclusion

Bullinger corresponded regularly with Calvin as well as monarchs including Edward VI and Elizabeth I of England, encouraging them in forming Protestant policies or resolving theological difficulties. He was also engaged in correspondence with Lutheran princes in Germany, such as Philip I of Hesse, one of the leaders of the Protestant faction in the Schmalkaldic War (1546-1547) fought to preserve Protestantism in Germany, as well as other reformers in England and elsewhere. In doing so, he helped spread Protestant belief further than any other reformer before Calvin.

Bullinger's primary focus was on improving the lives of others and assisting in addressing both their physical and spiritual needs. To this end, he worked consistently to resolve differences between Protestant sects that led to violence and what he considered un-Christian acts. Although he was devoted to his family, he extended the same kindness, compassion, and inclusion shown to them to others, even in 1564 and 1565 when he lost his wife and a daughter (or daughters) to the plague and was afflicted himself.

He died on 17 September 1575, after 40 years in the ministry working to spread the Protestant vision and heal its divisions. His efforts would allow Calvin to develop a systematic theology, addressing points that divided Lutheran and Reformed faiths, even though, to this day, some of that discord remains. In the present day, he is overshadowed by the better-known figures of Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin, but, in his time – and immediately afterwards – he was regarded as the foremost thinker and writer of the Reformation, whose works were more widely read and far more influential than those of the major figures of the Protestant Reformation.