Heinrich Himmler (1900-1945) was the head of the Nazi SS (Schutzstaffel) organisation. One of the most powerful individuals in Nazi Germany, Himmler built up the SS from a small paramilitary unit to a vast organisation, which included armoured divisions, the Gestapo secret police, the Einsatzgruppen extermination squads, and the Death's Head units, which were responsible for the Holocaust, that is the murder of 6 million European Jews.

Early Life

Heinrich Himmler was born near Munich on 7 October 1900. His father was a schoolmaster, and the family was Catholic. The historian N. Stone notes that the Himmlers were "a family socially pretentious but materially uneasy" (82). Heinrich had an unremarkable education and then found himself too young for active service in the First World War (1914-18), but he did train as an officer cadet. After the conflict, Heinrich achieved a diploma in agricultural studies at the technical college in Munich; significantly, given his future ideas on race, he had specialised in genetics and breeding. The small bespectacled Himmler found rather unglamorous employment as a salesman of fertilizer. Eager for more out of life, in 1923, Heinrich joined the fascist National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), or Nazi Party for short.

Rise in the Nazi Party

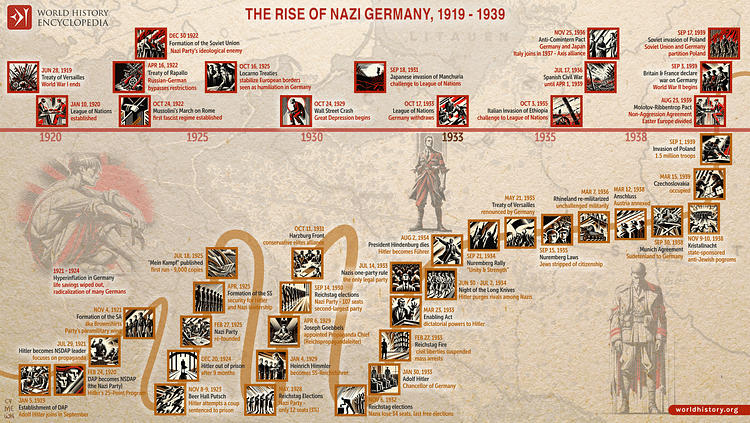

Himmler participated in the Beer Hall Putsch, the failed Nazi coup in November 1923, when he carried the banner of the Reichskriegflagge (Imperial War Flag), which later became almost a holy relic for the Nazis. When the party recovered from the fallout of the putsch, Himmler quickly rose in the Nazi hierarchy to become a deputy Gauleiter (regional governor). He found his real niche in the SS, the paramilitary organisation formed by the Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) as a counterbalance to the party's main paramilitary group the Sturmabteilung (SA or brownshirts). Himmler joined the SS in 1925 and became the deputy of the organisation in 1927. After impressing Hitler with a successful stint working in the Nazi propaganda department for the 1928 general election, Himmler was made head of the SS on 6 January 1929 and was given the title of Reichsführer-SS.

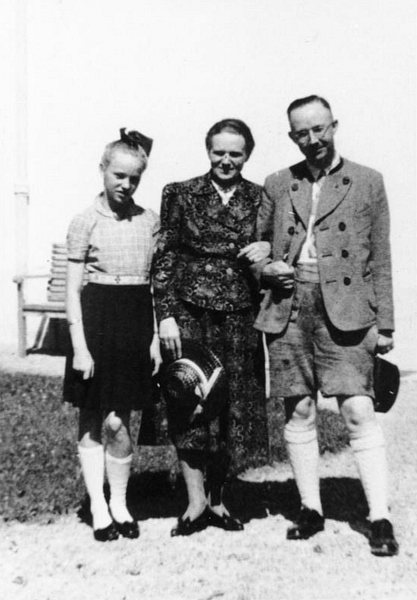

In the midst of his Nazi activities, Himmler found time in June 1928 to marry Margarete Siegroth, a nurse and clinic owner seven years older than him. Margarete sold her clinic to provide the funds to buy a farm outside Munich. The Himmlers raised chickens together and had a daughter, Gudrun (b. August 1929). Himmler was ambitious for much more than this and was keen to utilise his undoubted talents at organisation and planning. Hitler had outlandish ambitions for Europe, but Himmler even more so, including the total resettlement of Europe and the USSR with a new Germanic super race. Hitler's chief architect Albert Speer wrote that Himmler was "a visionary whose intellectual flights struck even Hitler as ridiculous" (373).

In 1930, as the Nazis pursued electoral domination, Himmler was elected a member of the Reichstag, the German parliament. In 1933, he was appointed head of the Munich police. The next year, Himmler took over from Hermann Göring (1893-1946) as the figurehead of the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police. In June 1936, Himmler was appointed the overall head of the German police forces. He was determined to reign over two powerful and overlapping branches of the Nazi state: the police in all its forms and the SS.

Character

Himmler was often regarded as a simple-minded man, even amongst his fellow Nazis. He loved order of all kinds – as a teenager he kept meticulous diaries of his every movement and long lists of all the books he had read and the letters he had both sent and received. As a young man, Hitler quickly realised that Himmler's greatest quality was his unflinching loyalty. Others saw different qualities and flaws. Speer noted of Himmler that "He gave me the impression of cold impersonality. He did not seem to deal with people but rather to manipulate them" (Speer, 94). Speer also described Himmler as vain and obsessive, but he was "also a sober-minded realist who knew exactly what his far-reaching political aims were" (Speer, 502-3).

Although he had tremendous power and opportunities, Himmler lived a frugal life and refrained from gathering around him the trappings of great wealth. The only thing that seemed to really interest him was collecting offices and titles, for which he had an insatiable appetite.

Himmler never enjoyed particularly good health, but after 1939, he experienced regular problems. "He had acute nervous headaches, stomach cramps, a predilection for quack cures and a mysticism that included faith in astrology and the power of mental suggestion" (Boatner, 218). He was not too ill to be systematically unfaithful to his wife, setting up one of his secretaries, Hedwig Potthast, in her own home in a country lodge when she became pregnant with his child (Helge, b. 1942); a second child, Nanette, was born in 1944. Himmler had separated from his wife in 1940, but the couple had long been estranged.

The Nazi Police Chief

In September 1939, a new Nazi organisation was created, the Reich Security Main Office or RSHA (Reichssicherheitshauptamt). This organisation controlled the Gestapo, the criminal police or Kriminalpolizei (aka Kripo), the police intelligence department the Sicherheitsdienst or SD, and a department responsible for gathering foreign intelligence. Himmler chose his able and utterly ruthless deputy to lead the RSHA: Reinhard Heydrich (1904-1942). Illustrating the overlap in state, police, and SS functions, Heydrich was also a lieutenant-general in the SS. The RSHA had three main roles: policing and repressing enemies of Nazism, gathering intelligence, and eliminating those people identified by the Nazis as being racially inferior. In none of these roles was the RSHA limited by any legal restrictions. Himmler's position allowed him to pry into the private affairs of every German citizen, and, with his absolute power of life and death over those citizens, he became, amongst an unfortunately large cast of Nazi villains, the most feared man in the Third Reich.

The SS: Himmler's 'Black Empire'

Despite all of his many and varied responsibilities, it was the SS that Himmler focussed on most. From its humble origins as a protection squad for Hitler, Himmler set about methodically creating an entirely autonomous Nazi organisation within the movement, effectively ensuring he became the feared head of "a state within a state" (Dear, 416). This organisation was to become the embodiment of Nazism.

In 1931, the SS Race and Settlement Office (SS Rasse- und Siedlungsamt) was created with Himmler's intention being that his organisation would become a sort of new aristocracy of pure-blooded Germanic people, or 'Aryans'. Obsessed with medieval knights and medieval chivalry, Himmler envisaged something of a throwback to the Teutonic Knights of old. To this end, he rebuilt Wewelsburg castle as his personal headquarters of SS folklore (he used slave labour to do it).

Himmler wanted his SS to become the biological, racial, and ideological elite of the Third Reich. In terms of recruitment, people with certain physical characteristics (e.g. tall, blond hair, and blue eyes), with a demonstrably pure Germanic heritage, and with an obvious fanaticism towards Nazi ideas were given special favour. The SS had its own system of ranks "modelled partly on military organizations, partly on monastic orders" (Dear, 814). Like monks, SS members underwent rituals of initiation, were expected to be absolutely loyal to the cause (with Himmler as the Abbot-General), and wore distinctive uniforms, in this case black. All of these features were designed to instil in SS members a belief in their superiority over everyone else, with the consequence that they would enthusiastically carry out such orders as mass executions of innocent civilians.

Himmler first prioritised scaling up the SS organisation by pursuing a recruitment drive. Consequently, by the end of 1933, the SS had over 200,000 members. Himmler then set about eliminating the SS's paramilitary rival, the SA. On 30 June 1934, in an event known as the Night of the Long Knives, the leaders of the SA were arrested and executed. Nothing could now challenge the primacy of the SS, which assumed SA functions like running the Nazi concentration camps, a role performed by special 'Death's Head' SS units (SS-Totenkopfverbände) and one which became greatly expanded with the outbreak of the Second World War (1939-45).

The Waffen-SS (meaning 'weapons' or 'armed' SS) was created as the armed branch of the organisation. Himmler envisaged the Waffen-SS as an elite element of the German armed forces with better training and equipment than regular units. This dream was only partially realised, but the Waffen-SS did grow to 600-800,000 members and fought on both the Western and Eastern fronts, usually as armoured divisions deployed where the enemy was strongest. Besides German and Austrian recruits, volunteers were taken from suitably 'Germanic' conquered countries like Norway and Denmark, but, as the war dragged on and casualties increased, volunteers were also taken from any conquered territories. The Waffen-SS had its own cadet schools, but senior officers often came from the regular army. Himmler personally gave SS officers a reward for bravery: a silver death's head ring. Inside the ring was inscribed the date: 30.6.34, the Night of the Long Knives. The fanatical Waffen-SS divisions were notorious for committing war crimes.

The SS was involved in other areas, notably economic activities such as using human hair and gold from dentures taken from victims of the concentration and death camps. Other commercial activities managed by the SS Main Office for Economy and Administration (SS Wirtschafts- und Verwaltungshauptamt), often employing slave labour, included the agricultural sector, quarries, forest and timber management, textile factories, and iron processing. There was even an archaeology department of the SS since Himmler was convinced that excavations could prove Germanic people had just as rich a past as the Italians could claim from ancient Rome. The SS even funded expeditions to Tibet to try and find links with Aryans there.

Himmler's ambition was for the SS to control, unrestricted by any laws, every aspect of state security in Germany and to ensure the transformation of Nazi policies into a practical reality for all citizens. As historians have noted: "Like no other institution of the Third Reich, the SS represents the arrogance of Nazi ideology and the criminal nature of Hitler's regime." (Dear, 814). Even further, Himmler wanted to control the minds of every person in the Third Reich. To this end, the SS sponsored propaganda campaigns using literature, posters, radio, and film to indoctrinate the population with Nazi ideology. Younger people received the same messages via SS-sponsored educational and research institutions. For Himmler, every citizen was to follow the motto he had given the SS: "loyalty is thy honour".

The Holocaust

As noted, the SS managed the Nazi labour and death camps. Himmler's deliberate policy of working detainees until they died meant there was little real distinction between the two types. In March 1933, Himmler had created the Dachau concentration camp, north of Munich. One of the first of its kind, it was meant to hold prominent enemies of the Nazi state, but this purpose was soon expanded. The number of people detained in the concentration camps rose from 25,000 in 1939 to 700,000 in 1945. Millions more were murdered in mass executions using firing squads, mobile gas vans, and the gas chambers of camps like Auschwitz. Those detained and murdered included Jewish people as part of the Nazi's Final Solution programme – the murder of all European Jews – but other significant groups to suffer included Romani people, Freemasons, Communists, intellectuals, homosexuals, prisoners of war, those with a physical or mental disability, political enemies, and anyone else the Nazis considered superfluous to their rule.

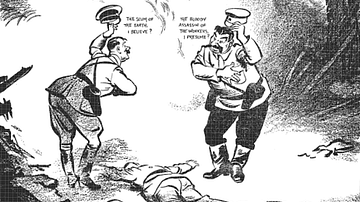

Himmler sent millions to their deaths, but he was himself squeamish about being present at any killings. On one of the rare occasions he was present at an execution, according to the Waffen-SS Colonel Karl Wolff (1900-1984), Himmler was splashed by blood and matter from a victim who was shot, and he almost fainted as a result. Wolff then told the SS group commander: "It serves him right that happened to him. It's quite right that he should see what he is ordering his people to do" (Holmes, 321).

In addition to the camps, the SS was directly involved in transporting innocent people to those camps using trains, a responsibility of the SS-Gestapo department led by the SS Lieutenant-colonel Adolf Eichmann (1906-1962). Another method of extermination of the innocent was the Einsatzgruppen, the mobile death squads, which worked behind the lines of the advancing regular army. Then there were the SS doctors, like Josef Mengele (1911-1979), who performed horrific medical experiments on people in the camps. Himmler ensured most of these activities remained highly secret or, at least, even if people had their suspicions, there was little concrete evidence of the scale of the horrors going on.

Himmler's Other Roles

Himmler was relentless in creating new offices and organisations for his SS empire, very often deliberately creating overlapping institutions so that power was divided amongst his subordinates while he remained aloof with the absolute power over everyone below.

In December 1935, Himmler founded the Lebensborn Registered Society, an organisation which aimed to promote population growth by encouraging members of the SS and police forces to have more children, often with partners they were under no obligation to marry. The Lebensborn organisation also found German foster homes for "racially suitable" children taken from occupied territories.

Himmler was made the Reich Commissioner for the Strengthening of German Nationhood in October 1939, which meant he was responsible for all racial matters. Himmler kept on gathering in the official appointments to ensure he had as many fingers in as many Nazi pies of power as he could get away with. Following the invasion of Poland in 1939, Himmler and his SS organisations were given free rein in those parts of the country annexed by the Nazis. Himmler was made minister of the interior in August 1943, which gave the SS chief yet more control over the Reich's civil service and judicial system.

It was only the fact that the war went badly for Germany in 1944 that restricted Himmler's ruthless grip over millions of European civilians. Himmler then played a duplicitous game of wait and see who succeeded during the 1944 plot to assassinate Hitler by top army and state officials who wanted to end the war. When the plot failed on 20 July, Himmler further ingratiated himself with Hitler with his relentless pursuit of the conspirators: arresting, torturing, and hanging thousands of suspects, including their children.

By the end of July 1944, Himmler had gained yet another appointment, this time as head of Germany's reserve army. One month later, he was tasked by Hitler to form last-ditch defence units, Volkssturm, principally a militia that recruited men too old for regular service and youths too young. In January 1945, Himmler was briefly appointed head of Army Group Vistula, which was tasked with the defence of Berlin against the advance of the USSR's Red Army.

Capture & Death

As the Red Army closed in on the German capital in April 1945, Himmler withdrew from Berlin to the safety of the Hohenlychen sanatorium in northeast Germany. He then moved further west to Schwerin. In the final weeks of the war, Himmler convinced himself that the Allies would settle for a peace deal and appoint him as the new leader of Germany. The SS chief made overtures to the Allies through an intermediary, Count Folke Bernadotte (1895-1948), but Hitler found out, was furious at his defeatist attitude, and promptly stripped Himmler of all his positions. Hitler also ordered Himmler be arrested, but Germany's most feared individual had already fled. Hitler had Himmler's adjutant executed as the next best thing. With the Red Army closing in on the Führer's Berlin bunker, Hitler committed suicide on 30 April. Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz (1891-1980) was appointed Hitler's successor, but he wanted nothing to do with Himmler and rejected his overtures in a meeting where Dönitz kept a gun on his desk.

With nowhere else to go, Himmler went on the run to try and return home to Bavaria. He disguised himself rather theatrically by shaving off his moustache and wearing an eyepatch. Pretending to be an ordinary soldier, he was intercepted on 22 May at a roadblock near Bremen and then questioned by the British Army. Realising the game was up, Himmler admitted who he was. While in custody, Himmler committed suicide on 23 May 1945 by taking a cyanide capsule. Medical staff had tried to keep Himmler alive during the 15 minutes it took for the cyanide to take effect. Himmler's body was buried in a secret location in an unmarked grave.

Himmler, if he had lived, would certainly have been found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity in the post-war Nuremberg trials which sought to bring the top Nazis to justice. Himmler's suicide meant that he escaped the hangman's noose. At the Nuremberg trials, the SS was classified as a criminal organisation. Ernst Kaltenbrunner (1903-1946), Heydrich's permanent successor as head of the Reich Main Security Office, was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity and hanged. Many more of Himmler's deputies were brought to justice, although some only paid for their terrible crimes decades later.