Heka is the god of magic and medicine in ancient Egypt and is also the personification of magic itself. He is probably the most important god in Egyptian mythology but is often overlooked because his presence was so pervasive as to make him almost invisible to the Egyptologists of the 19th and 20th centuries CE.

Unlike the well-known Osiris and Isis, Heka had no cult following, no ritual worship, and no temples (except in the Late Period of Ancient Egypt, 525-323 BCE). He is mentioned primarily in medical texts and magical spells and incantations and, because of this, was relegated to the realm of superstition rather than religious belief. Although he is not featured by name in the best-known myths, he was regarded by the ancient Egyptians as the power behind the gods whose names and stories have become synonymous with Egyptian culture.

Magic was considered present at the birth of creation - was, in fact, the operative force in the creative act - and so Heka is among the oldest gods of Egypt, recognized as early as the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000 - c. 3150 BCE) and appearing in inscriptions in the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 - 2613 BCE).

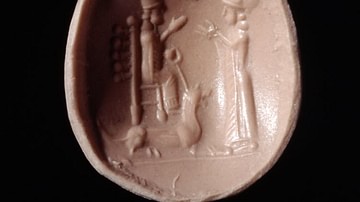

He was depicted in anthropomorphic form as a man in royal dress wearing the regal curved beard of the gods and carrying a staff entwined with two serpents. This symbol, originally associated with the healing god Ninazu of Sumer (son of the goddess Gula), was adopted for Heka and traveled to Greece where it became associated with their healing god Asclepius, and today is the caduceus, symbol of the medical profession. Heka is also sometimes represented as the two gods most closely tied to him, Sia and Hu and, beginning in the Late Period (525-332 BCE), he is depicted as a child and, at the same time, is seen as the son of Menhet and Khnum as part of the triad of Latopolis.

He is frequently seen in funerary texts and inscriptions guiding the soul of the deceased to the afterlife and is often mentioned in medical texts and spells. The Pyramid Texts and the Coffin Texts both claim Heka as their authority (the god whose power makes the texts true) and, according to Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson, "he was viewed as a god of inestimable power" who was feared by the other gods (110).

Heka referred to the deity, the concept, and the practice of magic. Since magic was a significant aspect of medical practice, a physician would invoke Heka in order to practice heka. The universe was created and given form by magical means, and magic sustained both the visible and invisible worlds. Heka was thought to have been present at creation and was the generative power the gods drew upon in order to create life.

In the Coffin Texts (written c. 2134-2040 BCE) the god speaks to this directly, saying, "To me belonged the universe before you gods came into being. You have come afterwards because I am Heka" (Spell, 261). Heka, therefore, had no parents, no origin; he had always existed. To human beings, he finds expression in the heart and the tongue, represented by two other gods, Sia and Hu. Heka, Sia, and Hu were responsible for creation as well as for maintenance of the world and the regulation of human birth, life, and death.

Creator, Sustainer, Protector

At the beginning of time, the god Atum emerged from the swirling waters of chaos to stand on the first dry land, the primordial ben-ben, to begin the act of creation. Heka was thought to have been with him at this moment and was the power he drew upon. Wilkinson writes:

For the Egyptians, heka or 'magic' was a divine force which existed in the universe like 'power' or 'strength' and which could be personified in the form of the god Heka...his name is thus explained as 'the first work.' Magic empowered all the gods and Heka was also a god of power whose name was tied to this meaning from the 20th Dynasty onward by being written emblematically with the hieroglyph for 'power,' although originally the god's name may have meant 'he who consecrates the ka' and he is called 'Lord of the Kas' in the Coffin Texts. (110)

The ka was one of the nine parts of the soul (the astral self) and was linked with the ba (the human-headed bird aspect of the soul which could travel between earth and heaven) which, at death, became transformed to the akh (the immortal soul). Heka was therefore originally the deity who watched over one's soul, gave one's soul power, energy, and allowed it to be elevated in death to the afterlife. Because of his protective powers, he was given a prominent place in the barque of the sun god as it traveled through the underworld at night.

Every evening, when the sun went down, the ship of the sun god descended into the underworld where it was threatened by the serpent Apophis. Many gods are credited with sailing on the ship through the night as protectors to ward off and try to kill Apophis, and among these was Heka. In some myths, he is also referenced as protecting Osiris in the underworld and, as the power behind magical incantations and spells, would have also been present when Isis and Nephthys brought Osiris back to life after his murder.

Heka was, therefore, the protector and sustainer of humanity and of the gods they worshiped as well as the world and universe in which all lived. In this way, he was a part of the central defining value of Egyptian civilization: ma'at - the harmony and balance which allowed the universe to function as it did.

Heka, Sia, & Hu

From the time of the Early Dynastic Period, and developed during the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE), Heka was linked to the creative aspects of the heart and the tongue. The heart was considered the seat of one's individual personality, thought, and feeling, while the tongue gave expression to these aspects. Sia was a personification of the heart, Hu of the tongue, and Heka the power which infused both. Egyptologist Geraldine Pinch explains:

The intellectual powers that enabled the creator to bring himself/herself into existence and to create other beings were sometimes conceptualized as deities. The most important of these were the gods Sia, Hu, and Heka. Sia was the power of perception or insight, which allowed the creator to visualize other forms. Hu was the power of authoritative speech, which enabled the creator to bring things into being by naming them. In Coffin Texts spell 335, Hu and Sia are said to be with their 'father' Atum every day...the power by which the thoughts and commands of the creator became reality was Heka. (62)

In the same way that Heka, Sia, and Hu enabled the gods to first create the world, they allowed human beings to think, feel, and express themselves. One of the ways in which people did this was through the use of magic. There was no aspect of ancient Egyptian life which was untouched by magic. Egyptologist James Henry Breasted comments on this:

The belief in magic penetrated the whole substance of [ancient Egyptian] life, dominating popular custom and constantly appearing in the simplest acts of the daily household routine, as much a matter of course as sleep or the preparation of food. (200)

Magic, in fact, defined the culture of the ancient Egyptians. It not only explained how the world came to be and how it functioned but allowed one to interact with the primordial divine forces which had created life and so influence one's own fate. Magic, in this respect, differed from the worship of the gods in the temples because it was a private interaction between a magician and the gods. This is frequently seen in the medical texts of ancient Egypt as the doctor invokes various deities to cure different diseases.

Heka & Medicine

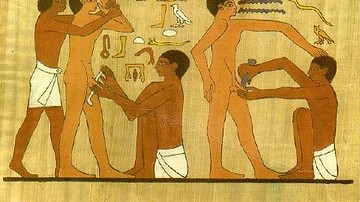

In the present day, most people do not associate magic with medicine, but for the ancient Egyptians, the two were almost one discipline. The Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE), one of the most complete medical texts extant, claims that medicine is effective with magic just as magic is effective with medicine. Since disease was thought to have a supernatural origin, a supernatural defense was the best course. Diseases were caused either by the will of the gods, an evil demon, or an angry spirit, and spells against these demons and spirits (or invoking the help of the gods) were common cures for sickness throughout Egypt's history.

Egyptian doctors (known as Priests of Heka) were not trying to trick a patient with some sleight of hand but were invoking real powers to effect a cure. This practice (heka) called upon the deity which made it possible (Heka) as well as other gods who were thought to be especially helpful in whatever disease presented itself. Egyptologist Jan Assman explains:

Magic in the sense of heka means an all-pervading coercive power - comparable to the laws of nature in its coerciveness and all-pervadingness - by which in the beginning the world was made, by which it is daily maintained, and by which mankind is ruled. It refers to the exertion of this same coercive power in the personal sphere. (3)

In medicine, the laws of nature as personified by the gods were invoked in order to cure a patient, but heka was also practiced in many other areas of one's life and, often, in the same way.

Heka in Daily Life

The physician-priest who was called to one's home would use amulets, spells, charms, and incantations to cure the patient, and these same would be used by people every day in any other circumstance. Amulets of the djed, the ankh, the scarab, the tjet and many other Egyptian symbols were commonly worn for protection or to invoke the aid of a god. Tattoos in ancient Egypt were also considered powerful forms of protection and the god Bes, a powerful protective deity, was among the most popular.

Bes watched over pregnant women and children but was also a general protective deity who infused life with joy and spontaneity. This particular god illustrates well how Heka was understood by the Egyptians in that he was definitely an individual with a recognizable character and sphere of influence, but the force, the power, by which he operated and through which one could communicate with him was Heka.

Magical practices such as the wearing of an amulet, inscriptions above or beside a door, hanging vegetables like onions to ward off evil spirits, reciting a certain incantation or spell before starting on a journey or simply going fishing, all of these were invoking the power of Heka no matter what other deity was called on.

One of the best examples of this, besides the medical texts in general, is the relatively unknown spell, The Magical Lullaby, which was recited by mothers to protect their children at bedtime. In this short poem (dated 17th or 16th century BCE), the speaker orders evil spirits out of the house with a warning of the spiritual weapons she has at her disposal. No specific deity is invoked (although Bes amulets or images were frequently hung in a child's room), but it is clear the speaker has the ability to keep the child safe from harm and the authority to issue the warning; that authority would have been the power of Heka in action.

The Underlying Form

Magic enabled a personal relationship with the gods which linked the individual to the divine. In this way, Heka can be seen as the underlying form of spirituality in ancient Egypt regardless of the era or the gods most popular at any time. Heka was honored throughout Egypt's history from the earliest times through the Ptolemaic Dynasty (332-30 BCE) and into Roman Egypt. There was a statue of him in the temple of the city of Esna where his name was inscribed on the walls. He was regularly invoked for the harvest, and his statue was taken out and carried through the fields to ensure fertility and a bountiful crop.

As Christianity became more dominant in the 4th century CE, belief in a magically infused world of the gods diminished and Heka was forgotten. This was in part due to the elevation of the god Amun during the New Kingdom (c.1570-1069 BCE) who became so transcendent he was regarded as pure spirit, eclipsing Heka, and providing a precursor for the Christian god. Even so, the concept of a force which encourages transcendence, sustains and maintains life, was not.

The Greek and Roman Stoics would later write of the Logos and the Neo-Platonists of the Nous - a force which flowed through and bound all things together but was, at the same time, distinct from creation and eternal - and so Heka lived on under these different names. The influence of the Neo-Platonists on the development of religious beliefs is well established, and so Heka continued as he always did; the invisible force behind the visible gods.