Hel is the queen of the afterlife realm of Hel in Norse mythology. She is the daughter of the god Loki and giantess Angrboda and sister of Fenrir the wolf and Jörmungandr the World Serpent. Although often referenced as a goddess, Hel is more of a half-goddess and jötunn, an entity from Jotunheim, realm of the giants.

Her name means "hidden" and refers to the dead who are either buried or cremated and whose souls are invisible to the living. Most scholars agree that she did not exist in pre-Christian Scandinavia and is more or less a creation of the Icelandic mythographer Snorri Sturluson (l. 1179-1241) who preserved the Norse sagas. Sturluson was a Christian writing for a Christian audience, however, and so is understood to have altered certain aspects of the pagan tales to make them more acceptable to Christians.

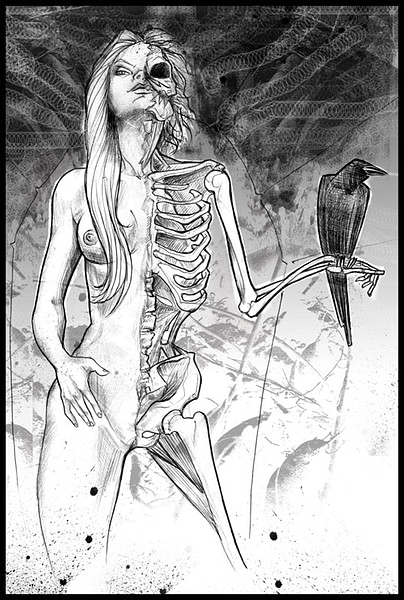

Hel is thought to be an example of this alteration as, previously, it seems that Hel was a place and synonymous with "the grave" having no supernatural being overseeing it. The entity Hel is depicted as half beautiful woman and half blue, decomposing corpse and does not resemble the character of Hela in the 2017 film Thor: Ragnarök (neither is she a sister to either Thor or Loki). She is sometimes referenced as a giantess since her mother, Angrboda, was one and lived in Jotunheim.

As noted, she is also referenced as a goddess in the modern day since she is the daughter of the god Loki. The primary sources, however, suggest she was a jötunn - not necessarily a giantess or a goddess - but someone descended from the jötnar of Jotunheim who could be a giant but might not be. No clear definition of her is available from the Norse texts and she is probably best understood as a supernatural entity (perhaps a demi-goddess) of normal size.

Origin of Hel & Loki’s Children

The original tales that make up the Norse sagas were passed down orally for centuries and only committed to writing in the Common Era. Prior to this time, writing took the form of runes with an alphabet of 24 characters, but these were only used for short pieces like memorials carved on stones or rune sticks. Scholar John Lindow comments:

Although the few rune sticks and other kinds of runic inscriptions that have been retained show that runes could be used in a great many ways, Scandinavia through the Viking Age was for all intents and purposes an oral society, one in which nearly all information was encoded in mortal memory – rather than in books that could be stored – and passed from one memory to another through speech acts. Some speech acts were formal in nature, others not. But like speeches that politicians adapt for different audiences, much ancient knowledge must have been prone to change in oral transmission. Without the authority of a written document, there was no way to compare the versions of a text and we therefore cannot assume that a text recorded in a thirteenth-century source passed unchanged through centuries of oral transmission. (11-12)

This is true of every aspect of Norse mythology but especially so regarding Hel. A number of modern-day scholars have concluded that there was no entity known as Hel in pre-Christian Scandinavian beliefs, among them Rudolf Simek who notes, "On the whole, nothing speaks in favor of there being a belief in a goddess Hel in pre-Christian times" (138) but, at the same time, it is acknowledged that one cannot really say for sure what the beliefs were prior to Christianity because there is no written record of them.

The first mention of Hel comes from the 13th-century Gylfaginning of the Prose Edda, chapter 34, where she is mentioned as one of Loki’s three children, born of the giantess Angrboda, living in Jotunheim. The gods of Asgard receive a prophecy that these children will grow up to cause them distress, and Odin either sends for them or rides to Jotunheim to bring them back to Asgard himself where he can monitor their activities.

The three children are the young woman Hel, the wolf puppy Fenrir, and the little serpent Jörmungandr. Odin almost instantly hurls Jörmungandr into the sea and throws Hel down below the icy realm of Niflheim where he grants her 'authority' over the Nine Realms of Norse cosmology. This authority is limited, it seems, to the souls of the dead who will pass down Helvegr, the road of the dead, to her realm under Niflheim known as either Niflhel or Hel.

Odin keeps Fenrir the wolf at Asgard, for reasons that are never made clear, where he grows at an increasingly alarming rate until he is so enormous and so strong that the gods fear they will not be able to subdue him should he ever decide to turn on them. They trick Fenrir into agreeing to be bound with fetters made by the dwarves which hold him fast on an island and then leave him there. While this is going on, Jörmungandr has also been growing beneath the seas until he is so huge that he encircles the world of Midgard where the mortals live; he is then known as the World Serpent. While her brothers’ fates are unfolding, Hel sits as Queen of the Dead in her dark realm which she cannot leave any more than her subjects can.

The Land of Hel

The location of Hel was to the north and reached by a road that led downward, across a bridge over a river of spears, through a gate in a tall fence guarded by the wolf Garm. The realm of Hel was reserved primarily for those who died of old age or sickness (though there were exceptions including, it seems, for accidents) instead of gloriously in battle or from other causes.

The souls of warriors went to Odin’s Hall of Valhalla, those who drowned were taken by the goddess Ran, wife of the sea god Aegir, and those of common folk went to Fólkvangr ("field of the people") presided over by the goddess Freyja. Precisely who, besides the infirm or aged, wound up in Hel is unclear, but it was not a realm of punishment or torment. Souls were treated well in Hel, as is clear from the story of the god Baldr’s arrival there when the floor was covered in gold and the benches with fresh straw to welcome him. Simek notes that "Hel is not a place of punishment, not a hell, it is simply the residence of the dead" (136), but it is far from a pleasant place overall.

Once the dead have arrived, they can never leave, and their world is damp, dark, cold, and misty. Simek comments on the aspects of Hel’s palace:

Her hall is called Eljudnir 'the damp place', her plate and her knife 'hunger', her servant Ganglati 'the slow one', the serving maid Ganglot 'the lazy one', the threshold Fallandaforad 'stumbling block', the bed Kor 'illness', the bed curtains Blikjanda-bolr 'bleak misfortune'. (137)

Based on its mention in various tales, it seems any soul not of a warrior who died in battle could end up in Hel, but there is no reason given for a soul to find itself in Hel rather than Fólkvangr other than dying of disease or old age. At the same time, it seems there are quite a few souls in Hel that did not die from either of those causes, and the two most famous are the god Baldr and his wife Nanna.

The Death of Baldr

The tale of the death of Baldr seems to have been among the most popular of the Viking Age and is given detailed treatment by Sturluson in chapter 21 of the Gylfaginning of the Prose Edda. Simek notes that Sturluson "devotes one of the longest uninterrupted parts of his Edda to the myth of Baldr’s death and the description of his funeral" (27). The story is the only one to feature the entity Hel to any significant degree though, even here, she remains a shadowy figure.

The tale is fully told in the Prose Edda but a short poem, Baldrs Draumar ("Baldur’s Dreams") from the Poetic Edda contributes to it. In Baldur’s Dreams, Baldr is having nightmares, and this is upsetting the other gods because Baldr is universally loved. The Prose Edda describes him as:

Odin’s second son, of whom only good things are told: he is the best of all, and everyone praises him; his appearance is so beautiful and so bright that light shines from him [and] he is the wisest of the Aesir, the most eloquent, and the friendliest. (Gylfaginning, 21; Simek, 26-27)

Odin rides to the land of Hel and resurrects the spirit of a witch to ask her the meaning of these dreams. He notices that the realm has been prepared nicely for someone’s arrival and the witch’s spirit tells him it is all to welcome Baldr. The short poem ends with the witch telling Odin to return home and enjoy what time he has because he will return soon enough after Ragnarök during which he will be killed and the Nine Realms destroyed.

In the prose tale, Odin’s wife (and Baldr’s mother), Frigg tries to save her son by extracting a promise from all things, animate and inanimate, not to harm Baldr. As he is a friend to all, everything and everyone makes this promise without hesitation, and Frigg returns to her hall content. The other gods soon develop a sport of gathering and hurling various objects at Baldr which, because of their promise, bounce off him harmlessly. The trickster god Loki observes this one day and, feeling like causing trouble as usual, disguises himself as a woman and travels to Frigg’s palace in the land of Fensalir.

Frigg welcomes the visitor and asks what the gods are up to at Asgard. The woman tells him that they are engaged in their usual sport of launching things at Baldr and watching them bounce away and then casually asks if it is really true that all things in the Nine Realms took the vow not to harm the god. Frigg, suspecting nothing, tells her guest that everything and everyone took the vow except for the young plant mistletoe which she decided not to ask because it was so small and could never hurt anyone.

Loki leaves and gathers some mistletoe he finds to the west of Valhalla and then returns to Asgard where the game is still going on. Baldr’s blind brother Hodr is standing to the side of the group, sad because he cannot join in the fun. Loki places the mistletoe in Hodr’s hand and tells him he will help him play with the others and guide his aim. Hodr throws the mistletoe which pierces Baldr who then falls down dead.

Hel’s Terms

The gods are horrified and begin weeping and then Frigg appears and asks for a volunteer to journey to Hel and ask for the return of Baldr’s soul. Hermodr, referenced as Baldr’s brother but not Frigg’s son (so possibly a son of Odin, though this is not clear) accepts the mission and rides the lonely road of Helvegr to Hel’s realm. He rides for nine nights until he approaches the river of Hel, and, during this time, the gods have prepared Baldr’s funeral, and Baldr’s wife Nanna has killed herself in grief over her loss.

Hermodr is met at the bridge by Modgudr, Hel’s maid, who recognizes him as a living being, tells him he cannot enter Hel, and asks why he has come. Hermodr tells her he is seeking the shade of Baldr and Modgudr confirms he has arrived. Hermodr then jumps the wall of Hel (since he cannot pass through as a living being), landing in the queen’s hall, where he finds Baldr being honored, surrounded by all the grandest trappings. He spends the night in the hall, and the next morning he tells Hel of his quest and asks her to grant it.

Hel agrees to release both Baldr and Nanna back to the world of the living on one condition: everything and everyone in the Nine Realms must weep for him. Baldr and Nanna give Hermodr gifts to bring back to Odin, Frigg, and Frigg’s faithful servant Fulla, and then he leaves to deliver his message to the realms. All things begin to weep for Baldr as Hermodr tells his tale until he comes to the giantess Thokk, living alone in a dark cave, who refuses. Thokk tells him that she does not know this Baldr fellow and sees no reason to weep for him and, further, those that have died should remain with the dead. Thokk, it is suggested, is actually Loki in one of his forms, but Hermodr does not know this, and failing to get her to weep for Baldr, Hel’s terms are not met, and Baldr and Nanna remain in her realm until after Ragnarök.

Ragnarök

Ragnarök was the Twilight of the Gods when the present cycle of the Nine Realms ended in a cataclysmic battle between the forces of order and those of chaos. Ragnarök was decreed by the Norns – the Fates – and could not be stopped nor was there any reason given for it to happen but the gods, by their actions (and especially Odin’s), contributed to its inevitability by the way they treated Loki’s children.

After the death of Baldr, Loki was bound below the earth with a serpent above him that dripped burning venom on his head. At the same time, his son Fenrir was bound on the island, Jörmungandr was confined to the sea, and Hel was unable to leave her dark realm. In the Iron Wood, Loki’s former mate Angrboda was raising his grandchildren (Fenrir’s sons) the wolves Sköll and Hati since their father was imprisoned. Although Loki himself was justly punished for the death of Baldr, Odin and the other gods of Asgard were directly responsible for confining Loki’s children who were innocent of any wrongdoing and had been living peacefully with their mother in Jotunheim until they were kidnapped and abused.

At a given time, an army of the dead would rise as Fenrir broke his fetters and howled at the gates of Hel. Human relationships would fall apart, and traditions would be forgotten while, at the same time, the weather would drastically change, bringing three severe winters with no summers while Loki writhed under the earth as the venom struck him, causing earthquakes until he finally broke free.

The earthquakes would continue as the ship Naglfar, built from the fingernails of the dead, rose from the waves steered by the giant Hrym while Hel assisted Loki by providing him a second ship that brought Surtr and his fellow Fire Giants to the battlefield. Jörmungandr broke from the sea, sending tidal waves across the realms, as the forces of chaos met the gods and the heroes of Valhalla in battle. Almost all the gods are killed, including Odin, Thor, and Loki, and the Nine Realms sink in fiery destruction, but chaos is defeated and order maintained, giving birth to a new cycle of life and a whole new world of realms.

Conclusion

Hel does not feature prominently in the tale of Ragnarök but is understood to have helped assemble the army of the dead for the final event and to have supported Loki’s efforts. It is unclear whether she survives Ragnarök, but it seems unlikely as both Baldr and Nanna are released from the realm, suggesting that she who held the dead in place no longer had that power. She is probably destroyed in the World Fire unleased by the Fire Giant Surtr that brings down all of the Nine Realms.

Her supporting role at Ragnarök is in keeping not only with her nature but how she appears throughout the Norse tales. Her name, as noted, means "hidden" and she is always a player operating behind the scenes. Even in the story of the death of Baldr, she makes the briefest appearance of any of the characters.

This was most likely purposeful in that Hel represented death which rarely announces or calls attention to itself until it makes its appearance and takes someone away. This is suggested by her depiction as a young, healthy, beautiful woman when seen from one side and a blue corpse from the other. Death can change one’s life in the turn of a head or the blink of an eye, and finally, this is what Hel would have represented, possibly then encouraging the living to make the most of their time before that time was up.