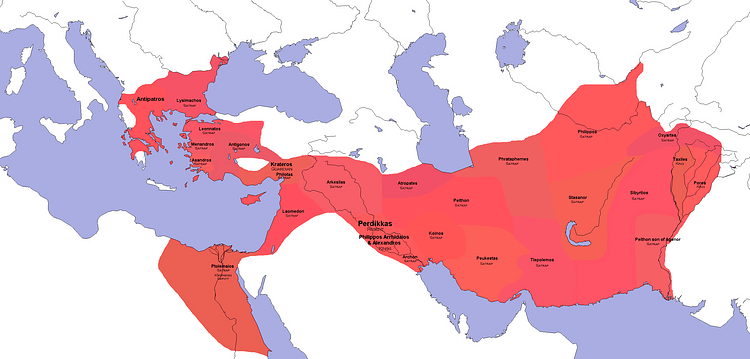

When Alexander the Great died in 323 BCE, he left behind an empire devoid of leadership. Without a named successor or heir, the old commanders simply divided the kingdom among themselves. For the next three decades, they fought a lengthy series of wars - the Wars of the Diadochi or Wars of the Successors - in a futile attempt to restore the tattered kingdom. Although the Hellenistic Age saw Greek language, art and philosophy flourish throughout Asia, there were few advances in military tactics. Instead, it was a time of “kingdoms and their armies.” The successors inherited an army borne out of the reforms of Philip II of Macedon. He was an innovator; the first Greek to master siege warfare, and with his son Alexander, they made Macedon the foremost power in both Greece and Asia. Together, Alexander and his father would create an army unlike anything the ancient world had ever seen.

Philip's Military Reforms

From his father Amyntas III and brother Perdiccas III, Philip acquired an army that was badly in need of restructuring. On his ascension to the throne in 359 BCE, he realized that the old ways were no longer dependable. He immediately initiated a series of major military reforms. To begin with, he increased the size of the army from 10,000 to 24,000, and enlarged the cavalry from 600 to 3,500. To make the army unified he issued new uniforms and made each soldier swear an oath to the king. A soldier was no longer loyal to his home town or province but loyal to the king and Macedon. While he retained the traditional phalanx - whose very nature required constant drilling and obedience - he made a number of improvements, adding a more effective shield and replacing the old Corinthian helmet with one that provided for better hearing and visibility.

Among several changes in weaponry, Philip added the ominous 18 foot sarissa which had the advantage of reaching over the much shorter spears of the opposition. Besides the sarissa, a smaller double-edge sword, or xiphos, for close-in-hand fighting was issued. And, lastly, he created a corps of engineers to develop siege weaponry. In the end Philip took a poorly disciplined group of men and turned them into a formidable, more professional army. This was no longer an army of citizen-warriors but an efficient military force, eventually subduing the territories around Macedon as well as subjugating most of Greece. It was this army that helped Alexander to cross into Asia and conquer the Persian Empire, but it was also the same army, with relatively few changes, that the successors used throughout their three decades of war.

The Wars of the Diadochi

The years that followed Alexander's death were ones without peace; it was a time of permanent war, or as one historian put it “a time of large scale rivalries.” Unlike the armies of Macedon who battled for Philip and Alexander out of loyalty, the soldiers who fought for the successors were mostly mercenaries - many were not Greek or Macedonian - without allegiance to any one or any place. They often fought for the highest bidder. For example, the commander Eumenes, an ally of Perdiccas, sent people throughout Asia Minor as recruiting agents before his battle with Antigonus. In 306 BCE Ptolemy, the regent of Egypt, bribed the army of Antigonus and his son Demetrius to defect.

Unlike the war against the Persians where men fought for an ideal and devotion to their king, these mercenaries fought in “nations without borders” in wars to simply solve political differences. These soldiers did not fight to defend their home and there was little loyalty among the successors themselves. They constantly made and broke alliances. This constant war and lack of loyalty among one's army made it easy to rely on the traditional military maneuvers (the phalanx). During the three decades of war, the real centers of power were the fortified cities along the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. The successors relied on those siege innovations developed during the times of Philip and Alexander, albeit improving their size, range and accuracy. Although Demetrius I of Macedon, appropriately named the Besieger, made some changes —- as seen in his attack on Rhodes, Greek siege technology would finally reach its height by the 2nd century BCE.

Siege Warfare

Siege technology was not new; however, it existed centuries before it reached Greece. By the 8th century BCE, the Assyrians had become the masters of siege warfare, holding their vast empire together with both siege strategies and terror - impaling a captive made many hesitant to surrender. These tactics - brought to fruition by their corps of engineers - included undermining walls, lighting fires beneath wooden gates, using ramps to breech walls, mobile ladders, and archers to provide cover. However, most importantly they developed the siege engine which was a multi-storied wooden tower with a turret atop and battering rams at the base. Some of these towers even had a drawbridge to deposit men on the top of a city's walls.

Initially, the Greeks failed to employ siege tactics successfully because their infantry, the heavily armoured hoplite, was thought to be ill-suited for its use. However, around the 4th century BCE basic siege tactics finally arrived in Greece. Early Greek warfare such as in the Peloponnesian War (460 – 445 BCE) had largely been defensive. Sparta had failed to take Athens because of her walls. Remember, it took over ten years for the city of Troy (according to Homer) to finally fall, and that was due to treachery - a wooden horse. This is not to say there weren't major offensive battles - Marathon and Thermopylae are excellent examples - but mostly, cities avoided such tactics. In one of the few clashes using siege technology the statesman and commander Pericles of Athens used rams and tortoises (sheds to the protect undermining of walls) to defeat Samos (440 – 339 BCE). Later, Sparta took Plataea (429 – 427 BCE) using ramparts (earthen embankments), siege mounds and battering rams. Unfortunately for the besieged, to win they used the oldest of all tactics, starvation. In the end Sparta won, selling the women into slavery, executing the men, and burning the city.

By 375 BCE Greeks were fully aware of the importance of siege weapons such as towers on wheels, scaling ladders, rams, and tunneling. With Philip's reforms the Macedonians were now the most powerful force in Greece, setting their sights eastward to the Persian Empire. Through his corps of engineers, he developed arrow-firing catapults and siege towers. Under Alexander, siege craft became a principal weapon in his efforts to defeat King Darius. His victories at Halicarnassus, Tyre and Gaza are testaments to alexander's use of siege weaponry. In the field he not only added a more mobile, lighter cavalry armed with javelins but also made better use of the Companion Cavalry, arming them with sarissas. Under the successors, major advances included the adoption of scythed chariots (as used by the Persians at Gaugamela) and the use of Indian elephants - Seleucus, Antigonus and Eumenes all used elephants.

The Lamian War

It did not take along after Alexander's death for the successors to begin quarreling among themselves. War almost immediately broke out. In Greece an Athenian by the name of Leosthenes, after hearing of the king's death, convinced his fellow Athenians and the neighboring Aetolians to go to war against Macedon. The regent Antipater responded instantly and the Hellenic or Lamian War began (323 -322 BCE). Unfortunately, Antipater was besieged at Lamia until Craterus arrived with additional troops. The war ended with the death of Leosthenes in the subsequent battle at Crannon in 322 BCE. Further south, in Egypt, tension increased between Perdiccas and Ptolemy. Perdiccas had control of Alexander's body and planned on returning it to Macedon where a newly-prepared tomb awaited it. Unfortunately, the body was stolen by Ptolemy and taken to Memphis. Perdiccas demanded it to be returned, and when it wasn't, he declared war. Three failed attempts to cross into Egypt; unfortunately, forced his men to rebel and kill Perdiccas in 321 BCE (no one else really liked him anyway).

Antigonus Against Eumenes

A major area of discord was between Antigonus I Monophthalmos (One-Eyed) and Eumenes - the regent of Cappadocia and head of Perdiccas's forces in Asia Minor. In 321 BCE at the Treaty of Triparadeisus where the old divisions of the empire formulated in the Partition of Babylon had been reaffirmed, Antigonus was given the daunting task of killing Eumenes (the treaty had condemned him to death). With Perdiccas dead, Eumenes was left without an ally; he later joined with Polypheron and Olympias, Alexander's mother.

In 317 BCE Eumenes - the commander of the Silver Shields - met with Antigonus at Paraetacene. Originally called the Shield Bearers, the Silver Shield were an elite group of hypaspists created by Philip II. After their heroics at Hydaspes, Alexander painted their shields silver, hence the name change. Although Eumenes inflicted greater casualties, Antigonus was considered the victor by a technicality. After the battle, Eumenes had chosen to return to the battlefield, camp and bury the dead. His men refused; they would not leave their baggage train. Antigonus, seizing the opportunity, camped there instead and cremated his dead which was the prerogative of the victor. Eumenes was incensed. The two would meet again at Gabiene where Eumenes would finally be defeated and meet his death (when his own men betrayed him). Supposedly, Antigonus allowed the former commander to starve for three days before sending someone to assassinate him. At that point Antigonus and his son controlled much of the territory from the Hindu Kush to the Aegean Sea.

The Successor Kingdoms

However, the wars over the Asian territory would continue. Seleucus had finally established himself in Babylon. In Greece Antipater's son Cassander gained control of Macedonia forcing the regent Polypheron out. Since Antigonus controlled much of the eastern Mediterranean, he and his forces marched into Babylon causing Seleucus to flee to Egypt and form an alliance with Ptolemy. After Antigonus besieged the island city of Tyre, he moved his army into Syria; however, his advances were stopped. His strong desire to reunite Alexander's kingdom brought Antigonus against the combined forces of Ptolemy, Lysimachus, Cassander, and Seleucus. After Demetrius was defeated by Ptolemy at the Battle of Gaza in 312 BCE, Seleucus took back Babylon. With this defeat, a very limited peace was declared.

Demetrius the BesiEger

The only successor to demonstrate an effective use of siege tactics was Demetrius, the Besieger. In his attack on the city of Rhodes, the capital of the island of Rhodes in the eastern Mediterranean (305 -303 BCE), Demetrius used a number of devices in his attempt to fell the city - mining, artillery, the helepolis or city-taker (a siege tower), carrying catapults, scaling ladders, and carrying rams.. His siege of Rhodes was actually part of an on-going war with Ptolemy. They both saw Rhodes's location and five harbors as an ideal trade center. Initially, Demetrius tried to take the city from the sea in a night assault with ships (the traditional trireme) which possessed stone-throwing artillery and archers. The Rhodians countered by destroying one of the ship's siege towers with fire. Another attack found the city sinking two more of Demetrius's ships. Realizing an attack from the sea was not going to be successful, Demetrius withdrew. Next, he attacked from the land, imposing a blockade with the hope of using the old-fashioned method of starvation.

It was at this time that Rhodes received help from Ptolemy who supplied the city with provisions. To counter, Demetrius used a 114 foot tower - the helepolis - which took 200 men to operate. Although he brought down the outer wall, to his surprise, the city had built an inner wall. With little choice, a temporary peace was reached. During the lull, Rhodes rebuilt the outer wall, adding a moat. Demetrius tried a second assault, but the city held on. After a 15 month siege, he finally relented and abandoned his assault. Utilizing the salvaged metal garnered from the abandoned siege towers, the people of Rhodes then built the Colossus of Rhodes, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

The successors continued to fight among themselves, but the siege of Rhodes marked the “high-water” mark of Hellenistic siege warfare. Although sieges would continue, the massive siege towers employed at Rhodes would never be used again. And, Demetrius would finally realize defeat. Lysimachus, the regent of Thrace, allied with the regents Seleucus and Cassander against the elderly Antigonus and Demetrius at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE; a battle that would bring about both the defeat and death of Antigonus. Lysimachus moved across the Thracian border into Macedon and forced Demetrius out. Demetrius and his army crossed the Hellespont into Asia Minor, confronting the forces of Seleucus. Unfortunately for the Besieger, he was immediately captured and died in captivity in 283 BCE. By 281 BCE, all of the old successors were gone -Antigonus, Demetrius, Seleucus, Lysimachus and Ptolemy were dead. Cassander had executed Alexander's wife Roxanne, his son Alexander IV and his mother. By all accounts the wars had ended. Three dynasties were all that endured, and they would fall one day to the Romans.

Conclusion

War had always been an essential part of Greek history. From the days of Homer and his stories of the siege of Troy in The Iliad, war had always been a source of glory or arête. The men who fought for Philip and Alexander did so out of loyalty, both their king and Macedon. The successors fought only to gain territory, using mercenaries to fight their battles. They maintained many of the old, traditional tactics of Alexander with few significant advances. Hellenistic warfare, at best, was merely a continuation of tried and tested strategies and weapons.

The true downfall of the successors and their kingdoms would come with the growth of Rome. During the conquest of Greece in the Macedonians Wars of the 2nd century BCE, the Greek phalanx met the Roman legion. The phalanx had always been effective throughout Greek history if only as a terrifying unit, but to be successful it had to fight on even ground and remain a solid unit - it was unsuccessful in individualised hand-to-hand combat. Unfortunately, the phalanx proved also to be inflexible. The Roman legion was far more efficient. The Macedonian Wars brought an end to Macedon and Greece and eventually to the dynasties of the successors. Rome not only conquered Greece but Asia Minor, Syria, Mesopotamia, and Egypt so that nothing remained of the great empire of Alexander.