Henricus (1611-1622, also known as Henrico, Henryco, Citie of Henryco) was a colony established in Virginia in 1611 by Sir Thomas Dale (l. c. 1560-1619). Dale had been ordered by the Virginia Company of London – which had funded the establishment of Jamestown Colony of Virginia – to locate a site for a new colony that would replace Jamestown as capital.

Dale’s mission was to find better land for a colony as well as to fortify it against possible attacks by the Spanish who objected to England’s colonization efforts in North America, claiming it was already theirs. The land Dale selected for the colony had formerly been inhabited by the Arrohateck tribe, one of the members of the Powhatan Confederacy, but Dale had attacked and indiscriminately slaughtered many of them to secure the site.

The Arrohateck retaliated by harassing Dale’s colonists on their march and after they had built the colony. Henricus was founded in the second year of the First Powhatan War (1610-1614) waged between the colonists of Jamestown and Wahunsenacah, also known as Chief Powhatan (l. c. 1547 - c. 1618), leader of the Powhatan Confederacy, but Dale refused to allow the conflict to interfere with establishing the colony.

In 1613, as part of the ongoing war, Wahunsenacah’s daughter Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617) was kidnapped by the colonists and held for ransom first at Jamestown and then Henricus where she met her future husband, John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622). Their 1614 marriage established the Peace of Pocahontas (1614-1622), which was broken when Wahunsenacah’s successor, Opchanacanough (l. 1554-1646) launched the Second Powhatan War (1622-1626), which destroyed Henricus, killing most of the colonists including (presumably) John Rolfe.

Colonists returned to the ruins toward the end of the war, but the population never grew to what it had been, and the colony was abandoned. The site of a proposed college nearby, however, attracted colonists who settled there after the war. The location of Henricus was lost during the 19th century but is thought to have been on the peninsula now known as Farrar’s Island and close to the modern-day Henricus Historical Park, a living history museum that preserves Henricus’ story through daily reenactments and exhibitions staged in a reconstructed 17th-century colony.

Jamestown & the First Powhatan War

Although Jamestown came to be known as the first successful English colony in North America, it did not show a great deal of promise at first. When the first English colonists arrived in 1607, they set up their new settlement in a swamp which contributed to a number of diseases that contributed to the deaths of the 100 men and boys who established the settlement. They arrived in May of 1607 and, by that fall, had lost almost half their number.

Contributing heavily to their difficulties was the fact that many of the colonists were aristocrats who had no experience in farming the land, and all, or almost all, had been led to believe that the Americas were laden with gold and one need not work at all in order to become wealthy. When they found this was not true, they resorted to stealing from the Native American tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy for food.

Wahunsenacah had initially provided them with food and supplies, hoping they would become his allies against the Spanish – who raided the coasts for slaves – as well as the hostile tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy. By 1609, however, relations between the Powhatan tribes and the colonists had soured as the English continued to encroach on native lands and steal food.

Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631) had formed a relationship with Wahunsenacah and taken measures to prevent thefts, but he returned to England in October 1609, and Wahunsenacah ordered the colonists to remain behind the walls of fortified Jamestown. Warriors of the Powhatan tribes were given leave to kill colonists found on Powhatan land, and this contributed to the period of Jamestown’s history known as the Starving Time during which 80% of the colonists died.

In May 1610, the new governor Sir Thomas Gates (l. c. 1585-1622) arrived, declared the colony a failure, and ordered it abandoned. He was setting sail with the survivors on the return trip to England when he was met by another ship carrying the aristocrat Thomas West, Lord De La Warr (l. 1577-1618) who ordered him about, and Jamestown was re-established. De La Warr instituted new policies of interacting with the natives which ignored their claims to the land and demanded their submission, setting off the First Powhatan War.

Sir Thomas Dale & Henricus

Sir Thomas Dale arrived while this conflict was ongoing and was undeterred by the violence. Dale had served in the English army, attaining the rank of captain, and was later knighted for distinguishing himself in combat against the Spanish, attracting the attention of the court of King James I of England (r. 1603-1625). He was especially noticed by James I’s son Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales (l. 1594-1612) who became his benefactor and suggested him for the position of deputy governor, in charge of law enforcement, in Virginia. Dale was well-suited for the job as he had already shown himself a strict commander who dealt harshly with infractions but his experience fighting the Spanish certainly recommended him further.

The Spanish had colonized the West Indies, South and Central America throughout the 16th century and had also taken the region corresponding to the modern-day State of Florida in North America. They then claimed the land all the way up the coast to modern-day New York State, stopping short of lands claimed by the Dutch and the French. Dale arrived in Virginia under the impression that a Spanish raid could be imminent and so, after establishing himself (and instituting his harsh law code which, in many cases, caused colonists to flee for refuge to the native villages) marched over 300 colonists to the new site and put them to work around the clock.

Dale himself sailed to the site up the James River but his men marched up inland. On the way, they were harassed by members of the Powhatan tribes under the leadership of the war chief Nemattanew (d. 1621). Nemattanew would continue actions against the English while they built the colony and Dale responded with surprise raids on native villages, the burning of their crops, and random acts of violence. He also imposed the same harsh rules and regulations on the Henricus workers as he had upon the Jamestown colonists when he had arrived.

In Jamestown, he had made an example of those who sought to evade their civic responsibility or fled to the Powhatans. Scholar James Horn quotes Dale in relating the punishments inflicted, writing, "some were hanged, some burned, some broken upon wheels, others staked and shot [and others] bound fast unto trees and so starved to death" (196-197). Dale’s same law code was applied in Henricus (named for his benefactor, Henry Frederick) and encouraged rapid development of the site.

In ten days, the colonists had enclosed seven acres of land within a wooden palisade and then raised watchtowers, built a church, and then public buildings and storehouses. The first hospital in the colonies, Mount Malady, was built on the other side of the river and construction was begun on the first college – the University of Henrico - intended to convert and educate the Native Americans in European Christian values. A large swath of land was cleared for this purpose a few miles above Henricus. Scholar Mary Miley Theobald comments:

Christianizing Virginia’s Indians was a priority with the Virginia Company and King James. They planned to build a college at Henricus to teach Indian children trades useful to the English and to train them as missionaries to their own people. One hundred English tenants were sent to work ten thousand acres of college land to provide income for the school’s support and more than 32,000 sterling was raised in churches throughout England to get the institution off the ground. But it was not to be. The Indians “proved very loathe upon any terms to part with their children,” Governor George Yeardley said. (2)

The colonists were oblivious to the Native American needs and culture, however, and the land continued to be cleared for building the college as work went on in Henricus itself and across the river from the main town. Captain John Smith, who never returned to Virginia but kept a close watch on its developments, describes the colony in his 1624 work, The General History of Virginia, as it looked when Dale was completing it:

This town is situated upon a neck of a plain rising land, three parts environed with the main river, the neck of land well impaled, make it like an island. It hath three streets of well-framed houses, a handsome Church, and the foundation of a better [one] laid, to be built of brick, [as well as] store houses, watch houses, and such like. Upon the verge of the river there are five houses, wherein live the honester sort of people, as farmers in England, and they keep continual sentinel for the town’s security…On the other side of the river, for the security of the town, is intended to be impaled [sites known as] Hope in Faith and Coxendale, secured by five of our manner of forts…and Mount Malado, a guest house for sick people, a high seat and wholesome air, as well as Elizabeth Fort and Fort Patience. (421)

As Henricus developed, it attracted more colonists from Jamestown. Among them was John Rolfe, who had arrived in Virginia with Sir Thomas Gates in 1610, carrying hybrid tobacco seeds with which he experimented to produce a better crop than previously available. Tobacco had proven itself a profitable export for the Spanish and was widely cultivated in their South American colonies. The English had attempted to cultivate the type known as Nicotiana rustica, which grew wild in North America and been used in various ways by the Native Americans, but this produced a bitter and much harsher tobacco than the Spanish cultivation of the southern plant Nicotiana tabacum. The Spanish guarded their tobacco plants and seeds zealously, but, somehow, Rolfe had gotten hold of a number of their seeds which did well in the Virginia soil, and he became a wealthy farmer by 1614. He established his tobacco farm, Varina Plantation, across the river from Henricus, completing it in 1615.

Henricus & Pocahontas

While Dale was busy with Henricus, De La Warr was still managing the First Powhatan War from Jamestown but, falling ill in 1613 CE, turned his authority over to Sir Samuel Argall (l. c. 1580-1626). Argall made no changes to De La Warr’s war policies and, looking for some advantage, found Wahunsenacah’s favorite daughter Pocahontas living in a village within his reach. He tricked her into visiting his ship, kidnapped her, and brought her to Jamestown in 1613. He then moved her to Henricus, holding her for ransom against the return of prisoners, tools, and weapons taken by the Powhatan. Wahunsenacah complied with Argall’s demands but Pocahontas remained captive as Argall claimed the Powhatan chief had not fully honored the terms of exchange.

Pocahontas was turned over to the Anglican priest Alexander Whitaker (l. 1585-1616) whose plantation, Rock Hall, was located at Henricus. Since one of the stated goals of the English colonies was the evangelization of the natives, the conversion of a notable figure such as Pocahontas, it was thought, would encourage others of the Powhatan Confederacy to become Christians. Whitaker, in the words of scholar David A. Price, "was assigned the task of polishing Pocahontas’ English and teaching her the ways of a Christian lady" (152). Through Whitaker, Pocahontas converted to Christianity, met John Rolfe at Henricus, and married him in April 1614.

Their marriage received the blessings of Dale and Wahunsenacah and concluded the First Powhatan War. Relations between the immigrants and natives improved and they began trading regularly. At the same time, however, the profitable tobacco crop necessitated more land for the colonists and the Powhatan tribes were pushed further into the interior and off their ancestral lands. Pocahontas and Rolfe had a son, Thomas Rolfe (l. 1615 - c. 1660) in 1615 and left on a promotional tour of England in 1616 where Pocahontas died in 1617. Young Thomas (named after Thomas Dale) was left there in the care of Rolfe’s brother.

Indian Massacre of 1622

Wahunsenacah kept the peace, even after his daughter’s death, in honor of his grandson but he stepped down as chief shortly afterwards, dying c. 1618, and his half-brother Opchanacanough became Chief Powhatan. Opchanacanough also kept the peace while planning for an attack he hoped would drive the English from his lands and back to their own. He capitalized on the colonists’ obvious satisfaction over the conversion of Pocahontas and encouraged others of the tribes under him to express interest in doing the same. It has been claimed that Opchanacanough initiated hostilities in response to the killing of Nemattanew in 1621, but it seems clear that plans were in place long before this event and, besides, Nemattanew seems to have been justly killed in retaliation for the murder of a colonist and was never among Opchanacanough’s favorites anyway.

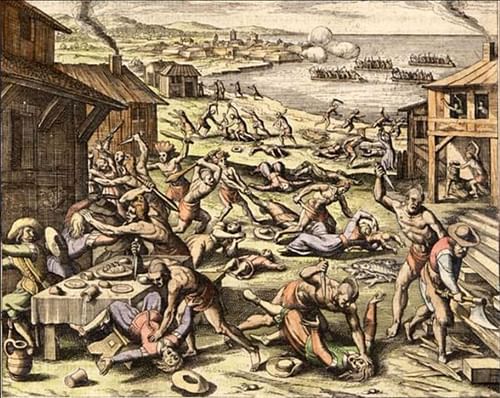

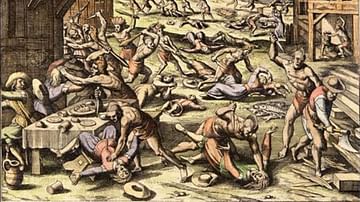

Natives and colonists came and went from Henricus and other villages all around Jamestown as the Peace of Pocahontas held. Natives were often welcomed into colonist’s homes to trade or share a meal, and some members of the tribes worked in the colonies as laborers or servants. None of the colonists, therefore, had any warning when Opchanacanough launched his attack (later known as the Indian Massacre of 1622) on Good Friday, 22 March 1622. At a given signal, natives in the homes and towns of the colonists rose up and killed the English while the warriors of the whole Powhatan Confederacy moved swiftly to burn the villages and kill even more colonists. The plan, to destroy the settlements one by one, and quickly before an alarm could be raised, worked well except for the Jamestown Colony which had been warned by a native boy who had become attached to one of the colonists.

Over 300 colonists were killed in one day, and Henricus was among the settlements destroyed by fire. John Rolfe, who is known to have died in 1622, was most likely killed at Henricus. The native warriors destroyed Mount Malady and set fire to the University of Henrico, and by nightfall, Dale’s colony was a smoldering ruin. Opchanacanough then waited to see the colonists’ response, hoping the attack had the desired effect and they would leave, but he would be disappointed. The colonists regrouped and fought back through a series of raids on Powhatan villages, recreating the tactics, losses, and deaths of the First Powhatan War in the second one. Opchanacanough sued for peace in 1626, but hostilities continued through 1629.

Conclusion

Dale had also developed the City of Henricus which grew up from the town beside the fortifications which, after March 1622, was also in ruin. Colonists from Jamestown and former Henricus citizens returned to settle there, but in 1623, it was reported that the site had been "left to the Indians". There is some evidence it was reinhabited by the English in 1624 and that the area cleared for the college supported some colonists, but Henricus was never rebuilt.

The ruins of the colony were still noted by travelers in the 18th century and were also recorded by writers during the American Civil War (1861-1865). In 1864, the Union Army dug a canal in the area (the Dutch Gap Canal) which destroyed the ruins, and later development of the area further obscured the site so that by the 20th century the general area of Henricus was known but not the exact location.

In 1985, a group was organized to preserve the history of Henricus, and this was incorporated in 1987 as the Henricus Foundation. Through donations and grants, the Henricus Foundation was able to establish the living museum of the Henricus Historical Park, which hosts thousands of visitors every year who come to hear the story not only of Henricus and the English colonists but of the Powhatan tribes displaced by them.