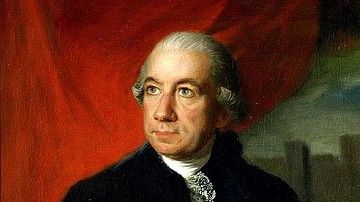

Sir Henry Clinton (l. c. 1730-1795) was a British military officer who served as commander-in-chief of the British Army in the later stages of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Having arrived in Boston in May 1775, he served in North America for most of the war, resigning his post in 1782 after the British defeat at the Siege of Yorktown.

The son of a British admiral, Clinton became a soldier at the age of 15 and saw action in Germany during the Seven Years' War. Thanks to his connections to British lords, he quickly rose through the ranks and was one of three British generals sent to Boston, Massachusetts, in 1775 to crush the American rebellion. Clinton was famously jealous, paranoid, and quick-tempered, traits that made it difficult for him to work with his fellow officers; still, he was well-educated in military matters and was among the most competent British tacticians of the war. As commander-in-chief, he led the British army at the Battle of Monmouth and the Siege of Charleston, but his lack of support for his second-in-command, Lord Charles Cornwallis, contributed to the British loss of the American South. After the war, he returned to England, where he received much of the blame for the British defeat before his death in December 1795.

Early Career

Little is known about Clinton's early life or childhood. He was likely born on 16 April 1730, although the time and location of his birth have been disputed; some scholars claim he was born in Newfoundland when his father was governor there, which, if true, would push his birth year back to 1732 at the earliest. What is known for certain, however, is that he came from a wealthy family of noble pedigree. His family was a cadet branch of the House of Lincoln, which could trace its earldom back to the reign of Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603), and his uncle was related by marriage to the first Duke of Newcastle, who often lent his patronage to the Clinton family (Willcox, 4). Henry's father was British Admiral George Clinton (not to be confused with the future U.S. Vice President of the same name) and his mother was Anne Carle, a general's daughter. He also had two siblings, both sisters, who survived to adulthood.

Through the Duke of Newcastle's influence, Admiral Clinton was appointed governor of the Province of New York in 1741. The admiral did not arrive to take up his post until September 1743, taking his family with him. Henry, who was at most 13 when he arrived in New York, was probably educated at the Long Island school of Samuel Seabury, the future first bishop of the American Episcopal Church. In 1745, he began his military career when he enlisted in the New York militia as a lieutenant. The following year, his father procured for him a captain's commission, and he was sent to join the garrison of Louisbourg, a fort on the Saint Lawrence River that had recently been captured from the French. While stationed there, he was ambushed by a band of French and Native Americans, narrowly avoiding death by "stripping and jumping into the sea" (Willcox, 10).

In the summer of 1749, Clinton realized his prospects for military advancement in the colonies were limited, prompting him to return to England. With Newcastle's help, he was commissioned as a captain in the illustrious Coldstream Guards and, by 1758, he had risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Grenadier Guards. By then, Europe was engulfed in the Seven Years' War (1756-1763) and Clinton's regiment was sent to Germany to bolster the Anglo-German army trying to prevent a French invasion of Hanover. He fought at the Battle of Villinghausen (16 July 1761) and Battle of Wilhelmsthal (24 July 1762), serving shoulder to shoulder with fellow British officers William Phillips and Lord Charles Cornwallis, both of whom would also become prominent generals in the American Revolution. He served as aide-de-camp to Charles William Ferdinand, future Duke of Brunswick, (the same Prussian general who would one day fight the French revolutionaries at the Battle of Valmy) in whose service Clinton was seriously wounded at Nauheim (30 August 1762).

Interwar Years

After the war, Clinton returned to London to settle the affairs of his father, who had died in July 1761. Securing his father's inheritance would prove a long and difficult process. He had to sue the Board of Trade for the unpaid salary owed to his father for his service as governor of New York, and also became embroiled in an ownership dispute over two large tracts of land his father had purchased in the colonies of New York and Connecticut (this dispute would end abruptly during the Revolution, when the Americans simply confiscated the properties). As Clinton dealt with these frustrating inheritance issues, his career continued to advance. In 1764, he was appointed Groom of the Bedchamber to the king's younger brother, the Duke of Gloucester, and in 1769, was sent to Gibraltar to act as second-in-command to the governor, Edward Cornwallis. He was promoted to major general in 1772 and, the same year, won election to Parliament, largely thanks to the influence of the dukes of Gloucester and Newcastle.

On 12 February 1767, Clinton married Harriet Carter, the 20-year-old daughter of landed gentry. Only six months later, Harriet gave birth to a son, Frederick, hinting that the couple had hastily married in order to avoid a scandal. Whatever the circumstances of their marriage, Henry and Harriet appear to have had a happy life together in their home in Surrey. In addition to baby Frederick, who would tragically die before his eighth birthday, the couple had four children born in rapid succession: Augusta (b. 1768), William Henry (b. 1769), Henry, Jr. (b. 1771), and Harriet (b. 1772). Both of Clinton's surviving sons would follow in his footsteps and become British generals during the Napoleonic Wars. But Clinton's blissful family life would be cut short. On 29 August 1772, only eight days after giving birth to her final child, Harriet died at the age of 26.

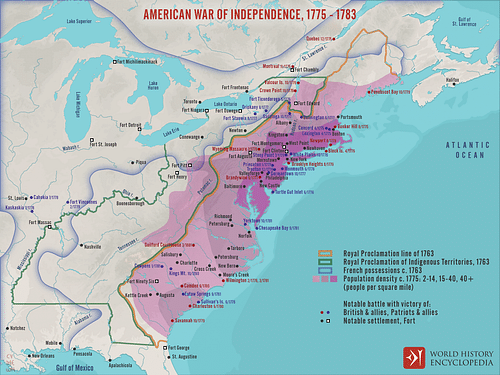

Clinton was overwhelmed with grief. He became reclusive and withdrew from public life, almost losing Newcastle's support when he failed to show up to his first session of Parliament. Gradually, however, Clinton "picked up the threads of his life" and, by April 1774, was well enough to embark on a military tour of the Russian army in the Balkans (Willcox, 32). He returned from this tour in October, just as the winds of war were gathering across the Atlantic; the quarrel between the British Parliament and the Thirteen Colonies over 'taxation without representation' was about to come to a head. In April 1775, the storm finally broke when New England militia and British soldiers spilled one another's blood at the Battles of Lexington and Concord. After the battles, the British soldiers retreated to the safety of Boston, Massachusetts, where they came under siege by a steadily growing army of Patriot militiamen. To restore the peace, the king dispatched a triumvirate of generals – Henry Clinton, William Howe, and John Burgoyne – to Boston aboard the ship Cerberus.

Arrival in America

Cerberus arrived in Boston Harbor on 25 May 1775, and its three passengers wasted no time conferring with General Thomas Gage, commander of the British military forces in North America. As the generals discussed ways in which the besieged British garrison could wriggle its way out of Boston, Clinton initially remained silent; he had always been a socially awkward man, having once described himself as a "shy bitch" (Boatner, 267). When he was finally induced to speak, Clinton recommended that they fortify Dorchester Heights, the high ground overlooking Boston from where they could overrun the American siege lines. Gage agreed, but before the plan could be put into action, the Americans fortified Breed's Hill on Charlestown Peninsula, a provocative position that necessitated an immediate British response. Clinton suggested a daring attack in which General Howe would lead a frontal assault up the hill while Clinton landed with 500 men on the western shore to attack the American position from behind.

This time, Gage rejected Clinton's plan, believing that only a frontal assault would be sufficient to drive the Americans from the hill. On 17 June 1775, at the Battle of Bunker Hill, the British did indeed drive the Americans off the hill, but at the horrendous cost of 1,054 men killed or wounded. Clinton, who spent the hours after the battle talking with dying British soldiers, blamed Gage for causing such unnecessary bloodshed by not adopting his plan. The king, too, thought that Gage had mishandled the Siege of Boston and recalled him to England; Howe replaced him as commander-in-chief, with Clinton moving up as Howe's second-in-command. In the remaining months of the siege, Clinton took up residence in John Hancock's abandoned mansion atop Beacon Hill. During this time, he hired a housekeeper, Mary Baddeley, the wife of a Loyalist officer; Clinton soon fell in love with Mary, who rejected his advances until she discovered her husband had cheated on her, at which point she began her own affair with Clinton. In the meantime, Howe had been planning to take some pressure off Boston by capturing Charleston, South Carolina, and opening another front in the South. Clinton was selected to lead this expedition and set sail for the Carolinas in January 1776.

Clinton, who spent the voyage south in a near constant state of seasickness, was reinforced by a detachment of fresh British soldiers under Lord Charles Cornwallis at Cape Fear, North Carolina. The expedition then sailed to Charleston, with Clinton dropping off his infantry forces on an island opposite the main rebel fortifications on Sullivan's Island. But the water was too deep for them to wade across, and Clinton's infantry could do nothing but watch as the ships of the Royal Navy, under Commodore Sir Peter Parker, launched an ineffective cannonade on the American fortress. Following this botched assault known as the Battle of Sullivan's Island (28 June 1776), the frustrated Clinton sailed back north to link up with Howe's main army on Staten Island in New York Harbor.

Overlooked General

By the time Clinton rejoined Howe, the British commander-in-chief's army had swollen to over 32,000 troops, and he was planning to attack the American fortifications on Lond Island. As these preparations were being made, three American Loyalists informed Clinton of an unguarded trail known as the Jamaica Pass, which wrapped around the American defensive positions on the Heights of Guan. Clinton took this news to Howe, volunteering to lead a division up the pass to outflank the Continental Army; despite the inherent risks (the informants could have been lying, after all), Howe agreed, and during the night of 26 August 1776, Clinton led the British vanguard up the Jamaica Pass, with Cornwallis' division in support. They successfully completed the march unnoticed and, the next morning, outflanked the Americans while the rest of the British army engaged in a diversionary frontal assault. The Battle of Long Island resulted in over 2,000 American casualties and ultimately led to the British capture of New York City.

Clinton was eager to capitalize on the success. As soon as the Americans had been driven from the Heights of Guan, he urged Howe to finish them off by assaulting their fortified position on the Brooklyn Heights; a successful attack could have wiped out the Continental Army and ended the war. Howe refused, believing that such an action would lead to another bloodbath like on Bunker Hill. Much to Clinton's chagrin, the British did nothing as George Washington brilliantly evacuated his army from Long Island during the stormy night of 29-30 August. Clinton also became frustrated by his superior general's conduct during the resultant New York and New Jersey Campaign. As the British chased Washington's dwindling army north, Clinton repeatedly offered plans to cut off the American retreat, each of which Howe rejected. Before long, the condition of Washington's army was much more secure, the opportunity of a quick British victory having passed; Clinton blamed Howe for mishandling the campaign, causing relations between the two men to quickly break down.

In December 1776, Clinton led an expedition that captured Newport, Rhode Island. The next month, he took a brief leave of absence to England, where he unsuccessfully lobbied for command of an army that was to push south from Canada; to placate him, he was given a knighthood and invested in the Order of the Bath. The newly made Sir Henry returned to New York City in July 1777 to find that Howe was off on his Philadelphia Campaign to capture the United States capital. Clinton once again believed that Howe was making a mistake, that he should instead be marching north to support General John Burgoyne, who had been given command of the Canadian army that Clinton had wanted. By the end of the year, it seemed that Clinton's instinct to not divide the British armies had been correct. Burgoyne was ultimately defeated at the Battles of Saratoga (19 September; 7 October 1777) and forced to surrender his entire army, while Howe, despite having captured Philadelphia, found that he was no closer to winning the war. For his part, Clinton tried to support Burgoyne by marching north in October; he captured two forts in the Hudson Valley Highlands and burned the New York capital of Kingston before news reached him of Burgoyne's surrender.

Howe resigned in early 1778 and was replaced by Clinton, who went to Philadelphia to take possession of the army. No sooner had he arrived than he was instructed by Parliament to evacuate the city and consolidate his forces in Manhattan; France had just entered the war as a US ally, and Parliament wanted to brace for a potential attack. Clinton obeyed and pulled out of Philadelphia on 18 June 1778. He was marching through New Jersey ten days later when he was attacked by the Continental Army at the Battle of Monmouth. The battle, which raged for hours in scorching summer heat, resulted in a draw, allowing the British army to finish their withdrawal to Manhattan. Washington followed, taking up a position in New Jersey, leading to a year-and-a-half-long stalemate in the north as each army stayed put, warily eying the other.

Commander-in-Chief

In 1779, Clinton and his officers began planning a 'southern strategy'; they meant to bring about the downfall of the United States by capturing the resource-rich South. In March 1780, Clinton sailed to Charleston with 10,000 men, laying siege from the land as Royal Navy vessels under Admiral Mariot Arbuthnot blockaded the harbor by sea. As the British siegeworks crept closer to the city walls, Clinton dispatched riders to capture all routes over the Cooper River, thereby trapping the American defenders in the city. On 12 May 1780, the Siege of Charleston ended in a British victory; the Americans surrendered not only the city but also their entire army within, amounting to some 5,000 officers and men. By this point, Clinton was no longer on speaking terms with his second-in-command, Lord Cornwallis, and had several shouting matches with Admiral Arbuthnot. In June, he took leave of them and returned to Manhattan to guard against an American attack.

He returned just in time to oversee his subordinate, German General Wilhelm von Knyphausen, launch a failed incursion into New Jersey at the Battle of Springfield (23 June 1780). As the two armies settled back into their respective camps, Clinton spent his time sending out raids into Patriot-controlled territories and plotting to take the stronghold of West Point, which controlled access to the Hudson River; through his favorite aide-de-camp, Major John André, Clinton negotiated with American turncoat Benedict Arnold for control of West Point. The plot was exposed, however, in September 1780, when Major André was captured and hanged by the Americans; Clinton's efforts to save André's life failed, as the Americans had refused to release André unless Clinton handed over Arnold, which he had been unable to do.

By the late summer of 1781, Clinton had grown exasperated with the lack of success of Cornwallis, who had been left behind to pacify the South after the initial victory at Charleston. Believing that the Americans intended to attack New York City, Clinton ordered Cornwallis to march to a port town and wait to be picked up by a British fleet that would ferry him back to Manhattan. Cornwallis begrudgingly obeyed, moving his army to Yorktown, Virginia, where it was soon besieged by a Franco-American army under Washington himself. Cornwallis surrendered on 19 October 1781, bringing the active phase of the Revolutionary War to an end. The following year, Clinton was replaced as commander-in-chief by Sir Guy Carleton and returned to England.

Later Life

Clinton spent his remaining years defending his conduct in the American Revolution. In his 1783 memoir Narrative of the Campaign of 1781 in North America, he blamed the ultimate British defeat on Cornwallis and wrote scathing pamphlets attacking General Howe as well. Nevertheless, Clinton still received much criticism for his handling of the war in its later stages and was widely blamed for the defeat, causing him to lose his seat in Parliament in 1784. Afterwards, he seems to have stayed out of the public eye until 1790, when he was re-elected to Parliament for Launceston in Cornwall. In October 1793, he was promoted to full general, and, the following year, he was appointed governor of Gibraltar. But just when it seemed as though his career was on the cusp of making a comeback, Clinton died in London on 23 December 1795, around the age of 65.