Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) was an American philosopher, writer, naturalist, and political activist. He is best known for his book Walden, published in 1854, which recounts his two-year experiment living alone in a small cottage at Walden Pond two miles outside Concord, Massachusetts, and his essay On the Duty of Civil Disobedience written in 1849 shortly after his release from a Concord jail for non-payment of a poll tax.

Early Life & Transcendentalism

Thoreau was born in Concord, Massachusetts, on 12 July 1817. He studied at Harvard College and his worldview was shaped by transcendentalism, a belief in the divinity of human nature, which was not a coherent philosophy but an attitude or state of mind that inspired many American intellectuals who flourished between 1820 and 1860. The movement's foremost representative, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) had given the Phi Beta Kappa commencement address at Harvard with Thoreau in attendance. Other notable transcendentalists were Margaret Fuller, Louisa May Alcott, Walt Whitman, and Bronson Alcott. They were young Americans who had been born into the Unitarianism of New England. According to Perry Miller in his American Transcendentalists, they responded to the new literature of England and the continent "revolting" against the rationalism of Harvard College. Although Protestant, they turned against the Protestant ethic, choosing instead to cultivate the arts of leisure to avoid making money. To some, it was intense individualism, but to others, it was sympathy for the poor and oppressed. Morris wrote: "…the self-reliance and self-determination exalted by the transcendentalists gave to American writers a freedom that vitalized the first period of national letters." (600)

Thoreau graduated in 1837 without distinction and returned to Concord; he viewed Concord as a microcosm of the world. Instead of seeking employment like his fellow graduates, he chose instead to become an observer and interpreter, a "thinker of thoughts, a student of nature and of literature – half-scientist and half-poet" (Mead, 112) He tried teaching for a while and even land surveying. In Walden he wrote, "I did not teach for the good of my fellow man but simply for a livelihood, this was a failure" (65). He even worked for a time in his family's pencil factory. An occasional odd job provided him with enough money to be clothed and fed. He became friends with Emerson, who took him into his home (1841-43) and offered him advice on the craft of poetry and writing. Thoreau moved briefly to New York, living with Emerson's brother, to try to sell some of his essays and poems, but he was unsuccessful.

Walden Pond

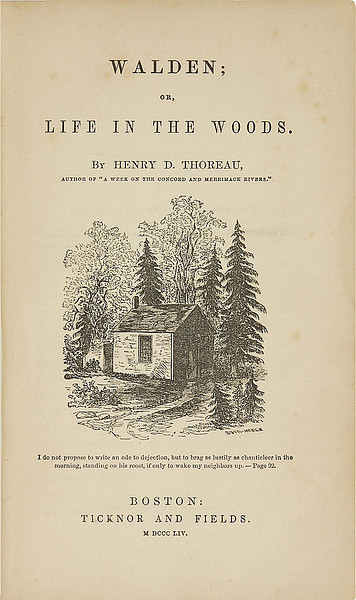

In July 1845, Thoreau built a small cottage on Emerson's land at Walden Pond outside Concord, and spent the next two years there alone. An occasional land surveying job earned him enough money to live. Having never been one to work very hard at any job, he later wrote in Walden, "I found that by working about six weeks a year I could meet all expenses of living" (65). At Walden, he had a small garden patch for potatoes and beans, and the pond provided fish. Although the cottage demanded maintenance, he still had enough leisure time to think, study, and write: "I am convinced by both faith and experience that to maintain one's self on this earth is not hardship but a past-time if we will live simply and wisely" (Walden, 66). During his time there, he wrote his first book, the poorly-received A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, published in 1849.

His most famous work, Walden, published years later, summarizes his experience of living in the cottage. In the opening paragraph of Walden, Thoreau wrote, "When I wrote the following pages or rather the bulk of them, I lived alone in the woods, a mile from my neighbor, in a house which I had built myself…and earned by living by the labor of my hands" (1). Part of his love for the isolation of the cottage was that he could be alone: "I found it wholesome to be alone, the greater part of the time" (128). To Thoreau, there were certain necessities of life: food, shelter, clothing, and fuel. He believed that when these four items are all satisfied, people are ready to face the problems of life with freedom and the possibility of success. Most of the luxuries and many of the "so-called" comforts of life "are not only not indispensable but positive hindrance to the elevation of mankind" (Walden, 62). In the conclusion of Walden, Thoreau wrote "Why should we be in such desperate haste to succeed … If man does not keep pace with his companions perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears" (307).

Poll Tax & Jail

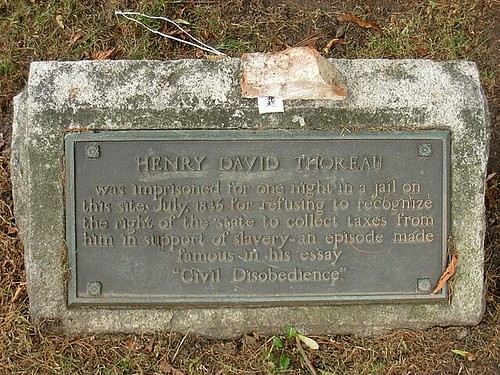

In 1849, after refusing to pay the poll tax, again, Thoreau was briefly jailed. He believed the tax had supported the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). His one-day jail sentence prompted him to write the essay On the Duty of Civil Disobedience. In defense of his short time in jail, Thoreau held that it was a citizen's obligation to resist an unjust law. The essay advocated both passive resistance and non-violence. He began citing the old motto "That the government is best which governs least" but Thoreau believed it should be amended to read "That the government is best that governs not at all" (Thoreau, 729). He is not advocating no government, but a government that addresses some of the major issues of the day: Western expansion of the United States and the Fugitive Slave Law.

Making a reference to the war, Thoreau held that it had been fought for both maintaining slavery and the expansion of slavery into the new territories. He believed that governments show how successfully men can be imposed up for their own advantage: "It is excellent we must all allow. ... Yet this government never of itself furthered any enterprise … It does not keep the country free. It does not settle the West. It does not educate" (729). He wished for a better government and believed that people should make known the kind of government that would command their respect: "All men recognize the right of revolution, that is the right to refuse allegiance to, and to resist, the government, when its tyranny or its inefficiency are great and unendurable" (732).

He then made a very controversial statement that may have inspired others to fight against injustice: "When a sixth of the population of a nation, which has undertaken to be the refuge of liberty are slaves, I think that it is not too soon for honest men to rebel and revolutionize" (732). The essay influenced 20th-century activists such as Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) and his fight for Indian independence, and Martin Luther King (1929-1968) and his battle for civil rights in the 1950s and 60s. Gandhi and King both acknowledged the inspiration they received from the essay.

Thoreau continued by saying that unjust laws exist, so people should commit to either obey them or amend them. Thoreau referred to his failure to pay the poll tax for six years. He relayed the incident that prompted the writing of the essay: "I was put into jail once on account for one night … I could not help being struck with the foolishness of that institution which treated me as if I were mere flesh and bones to be locked up" (Thoreau, 742). The state, in his words, does not intentionally confront a man's sense, intellectual or moral, only his body and senses. He believed that the state does not have superior wit or honesty but only superior strength. And he was doing his part to educate his fellow countrymen:

I simply want to refuse allegiance to the state – to withdraw and stand aloof from it effectually. ... I quietly declare war with the State, after my fashion, though I will still make use and get what advantage of her I can.

(Thoreau, 745)

Political Activism

Thoreau's political activism included a strong opposition to slavery, the defense of John Brown's uprising at Harper's Ferry, and his support for the outspoken abolitionist Wendell Phillips. Among his numerous speeches and lectures are Slavery in Massachusetts (1854) and A Plea for Captain John Brown (1859), which were later published as essays.

Slavery in Massachusetts was first delivered to the Anti-Slavery Convention in Framingham, Massachusetts, on 4 July 1854. Massachusetts, of course, was not a slave state; Thoreau's title is making reference to the state's support of the Fugitive Slave Law, part of the Compromise of 1850. The Law, a concession to the Southern slaveowners, required that all states must return runaway slaves. He wrote that while there were no slaves in Nebraska, there were at least one million in Massachusetts – a subtle reference to the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which allowed any incoming state to choose to allow slavery or not – a concept known as popular sovereignty.

Thoreau's primary concern was that the state and its governor did not take action against the Act or the return of runaway slaves. He spoke of the celebration of Concord's Revolutionary spirit:

Three years ago, just a week after the authorities of Boston assembled to carry back an innocent man and one whom they knew to be innocent into slavery, the inhabitants caused the bells to be rung … and to celebrate their liberty and the courage and the love of liberty of their ancestors who fought at the bridge.

(Thoreau, 862)

He said three million fought for the right to be free but hold in slavery three million others. He wrote that "every humane and intelligent inhabitant of Concord when he or she heard those bells … thought not … of the events of the 19th of April, 1775, but with shame of the events of the 12th of April, 1851" (862). The first date refers to the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the start of the American Revolutionary War, while the latter was the day Thomas Sims was sent back to bondage. In a criticism of the Supreme Court and the "so-called" judges decision that three million are and shall continue to remain slaves, he believed that Massachusetts should not concern itself with Nebraska and the Fugitive Slave Act, but with its own slaveholding and sovereignty. The state should dissolve its union with the slaveholders: "Show me a free state and a court truly of justice, and I will fight for them if need be, but show me Massachusetts and I refuse them my allegiance and express contempt for her courts" (Thoreau, 870).

Legacy

Thoreau's later essays demonstrated the effects of the tuberculosis that would take his life on 7 September 1862. His abilities as a writer would not be realized until after his death, but people are still reading his Walden and Civil Disobedience decades later, inspiring young and old alike. Historian Richard Morris in his Encyclopedia of American History wrote that in Thoreau the "individualism of the transcendentalist movement reached its influence and uncompromising form." (101)