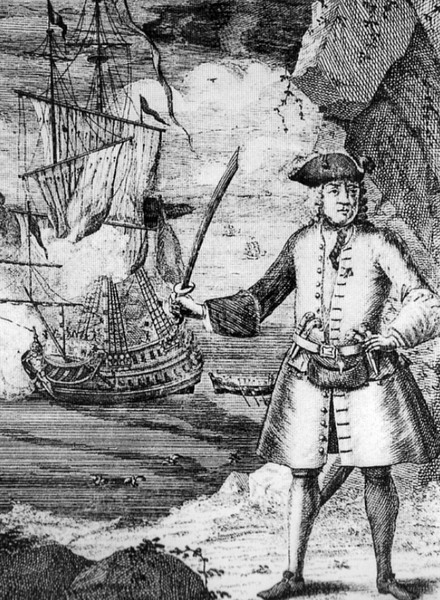

Henry Every (b. 1653), also known as Henry Avery, Benjamin Bridgeman, ‘Long Ben’ and (incorrectly) John Avery, was one of the most savage and successful pirates in the Golden Age of Piracy. Capturing a treasure ship of the Mughal emperor in 1695 with a cargo worth over $95 million today, he promptly disappeared and was never seen again.

Thanks to his jackpot capture of the Ganij-i-Sawai, Every gained the nickname ‘Arch Pirate’. It has long been said that Every’s huge success inspired many other mariners tired of hardtack and the lash to take up piracy in the hope of emulating his once-in-a-lifetime capture. Despite the bounty put on Every’s head, he completely vanished, although one legend has it that he lost his fortune to unscrupulous merchants and died in poverty in England.

Early Life

Henry Every was born in or near Plymouth, Devon, England: in 1653. He followed in his father’s wake and embarked on a career at sea, beginning with a position as mate on a merchant vessel. By 1690, he had joined the Royal Navy and served as a midshipman on the HMS Kent and HMS Rupert. He was, perhaps, involved in slave trading and piracy in the Bahamas, actions sanctioned by the corrupt governor there. Little else is known about Every before he gained infamy in the western Atlantic and the Indian Ocean, although a great many fictions have been attached to his early years.

Every was often called ‘Long Ben’ or ‘Long John’ which is curious since he does not seem to have been particularly tall. The historian D. Cordingly gives the following summary of Every’s physical appearance:

Henry Avery did not conform to any of the popular images we have of pirates today. He was of middle height, rather fat, with a dissolute appearance and what was described as a jolly complexion.

(Cordingly, 21)

Mutiny & Piracy

In 1694, Every joined the privateering ship Charles II (incorrectly called the Duke in some sources), which was part of an expedition funded by the Spanish Crown to attack buccaneers and French smugglers in the Caribbean. While docked at La Coruña in Spain in May 1694, and while the captain was drunk one night, Every roused 100 of the crew to mutiny. The mariners had grown restless after several months in port when their wages had not been forthcoming. Every was only the second mate on the Charles but the mutineers voted him their new captain. Every renamed the ship Fancy and headed for Madagascar in the Indian Ocean, joining forces with two pirate sloops on the way. When he reached the coast of Africa, the captain and those crew who had not supported the mutiny were put in a small boat and directed to row for the shore. The Fancy sported 46 cannons and so was a formidable sight for the generally poorly armed merchant vessels in the Indian Ocean.

Captain Every began his pirate career before he even arrived in the Indian Ocean. On route, he captured three English merchant vessels in the Cape Verde Islands and two Danish ships off Sâo Tomé before proceeding down the western coast of Africa. Every even captured a French pirate ship in the Comoros Islands, the vessel being on its way round the Cape of Good Hope. Captain Every then wrote an open letter to the English authorities, leaving it on Johanna Island in the Comoros archipelago in 1695. Addressed to all English commanders, it publicised his deeds and declared that "I have never as yet wronged any English or Dutch nor never intend whilst I am commander" (Cordingly & Falconer, 85). He seems to have forgotten his captures of the Cape Verde Islands.

Every flew the Jolly Roger flag, designed to encourage ships to surrender without a fight or face dire consequences. Every’s version had a skull and crossbones, with the skull in profile and the background red or, on other occasions, black. Based at the already established pirate haven on Madagascar, and perhaps becoming their leader, Every amassed a fleet of six pirate ships so that he could attack the really lucrative but well-protected merchant ships in the area: the annual treasure ships of the Mughal Empire.

The Ganj-i-Sawai

Every prowled the Indian Ocean and even sailed as far north as the Red Sea where he secured his largest prize by far in September 1695, the treasure ship owned by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, head of the Mughal Empire of India (r. 1658-1707). This floating Aladin's Cave of booty was the Ganj-i-Sawai (later called Gunsway in newspaper reports). The vessel had plenty of cannons and was further protected by a convoy, which was carrying additional treasure and pilgrims back from Mecca, including the wives of important officials. Every pursued the fleet over one night, caught up with the Fateh Mohammed and took it over. No small prize, the ship was boarded and a handsome £50,000 worth of gold and silver was taken (£10 million or $14 million today).

Every’s pirate fleet then turned its attention to the main target, the Ganj-i-Sawai, firing several broadsides as the ship neared the coast of Surat in northern India. With the Indian vessel having around 40 cannons and 400 soldiers on board, the battle took two hours, but the pirates won the day, albeit with heavy casualties. A cannon shot brought down the Ganj-i-Sawaj’s mainmast, and the pirates boarded the stricken vessel. Most of the passengers were killed outright or thrown overboard after they had been tortured to reveal the whereabouts of their personal valuables. Many of those women who did not jump overboard were raped. Every denied the violence of the capture, but one of his crew members, John Sparcks, gave the following confession to an official prior to his execution by hanging in London in 1696:

Expressed a due sense of his wicked life, in particular to the most horrid barbarities he had committed, which though upon persons of heathens and infidels…so inhumanely rifled and treated so unmercifully, declaring…that he justly suffered death for such inhumanity.

(quoted in Cordingly & Falconer, 89)

Every's pirates took loot worth at least £325,000 (£69 million or $95 million today) from the treasure ship. It was a staggering haul and one of the richest taken in the history of piracy at sea. Each crew member’s share was the equivalent of an entire lifetime of wages. This booty took the form of gold, silver, gemstones, coinage, precious spices, and rolls of silk. There were also luxury manufactured goods such as a saddle encrusted with diamonds.

The Mughal emperor responded to the dreadful loss by threatening the British government that he would attack British interests in India. He began by imprisoning all British traders in Surat and threatened to proceed to more drastic measures if the pirates were not more actively pursued. As it turned out, some of these traders were so harshly treated they died in prison. Aurangzeb's fury brought tremendous pressure on the East India Company who, concerned at the threat to trade if relations with the Mughal emperor soured, put a bounty on Every’s head. The British government had already offered a £500 reward for each member of Every’s pirate crew captured before the East India Company offered its own £1,000 per head bounty.

The pirates, though, had disappeared, first sailing to Sâo Tomé, then across to the Caribbean where they disbanded in the spring of 1696. The Fancy was sold to the corrupt governor of the Bahamas, but the governor of Jamaica refused a massive bribe to offer the pirates a royal pardon (the Bahamian governor did not have this power). Henry Every may have sailed up to Rhode Island and from there crossed the Atlantic to the greater safety of Ireland. In 1696, Captain Kidd (c. 1645-1701) was tasked with ridding the Indian Ocean of pirates and specifically, the capture of Henry Every, but he did not find him and turned to piracy himself. It is worthy of note that in a general amnesty for all pirates issued by the British government in 1698, both Kidd and Every were specifically mentioned as exceptions.

According to legend, Every returned to Bideford in Devon with a quantity of diamonds from his acts of piracy, but he was swindled out of them by a dishonest fence and obliged to live the rest of his days in poverty since if he renounced the fence then the authorities would discover his identity. There were several reported sightings of the English pirate in England in the next two decades, but none were substantiated, and his ultimate fate remains a mystery. What is certain is that he was one of the very few well-known pirates to escape the hangman’s noose or death in action. In contrast, 14 of his crew were eventually arrested, six of whom were hanged.

Legacy

The life of Every was the focus of an early-18th-century play popular for several years in Drury Lane’s Theatre Royal. The Successful Pirate took several large liberties with reality but helped establish Every as one of the legends of the so-called Golden Age of Piracy. The largest fiction was that Every had married Aurangzeb's daughter, who he had captured along with the Mughal emperor’s ship. The play ends with the pirate living in luxury at the Indian court.

A more factual biography, although still containing fictional embellishments, is found in the chapter on Every (where he is incorrectly called John Avery) in A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, compiled in the 1720s. The work was credited to a Captain Charles Johnson on its title page, but this is perhaps a pseudonym of Daniel Defoe (1660-1731). Scholars remain divided on the matter. Defoe was so fascinated with Every’s story that he had already written a separate account of his life, seemingly based on interviews and presented as two letters written by the pirate himself. Titled The King of the Pirates, it was published in 1719 but is, in reality, as much a heady cocktail of fact and fiction as the chapter in the General History, and the two works offer quite different accounts of Every’s life.