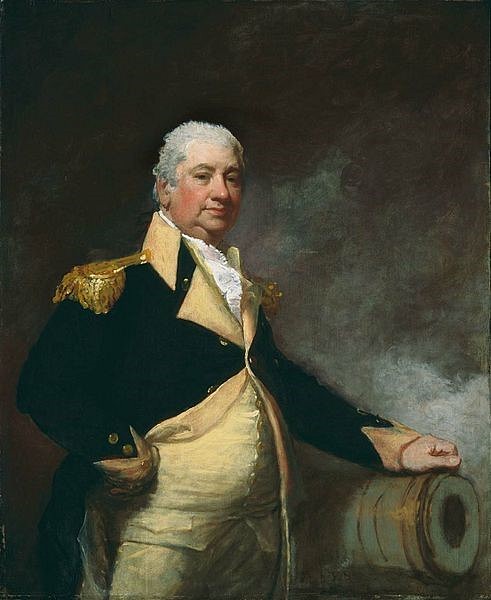

Henry Knox (1750-1806) was a Boston-born bookseller who became a general of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) and served as the army's Chief Artillery Officer. After the conflict, he was appointed the first Secretary of War of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1794 in the Washington administration.

Knox first distinguished himself in January 1776, when he guided his 'Noble Artillery Train' of 58 artillery pieces on a harrowing 300-mile trek across the snowy and mountainous terrain of New York State and Massachusetts; this effort helped the Continental Army win one of its first major victories at the Siege of Boston. Henry Knox commanded the Continental artillery for most of the American Revolution and was one of George Washington's most trusted subordinates. When Washington became President of the United States in 1789, Henry Knox was put in charge of the War Department. In this capacity, he sought to strengthen the military and helped create the Legion of the United States, a standing army of professional soldiers, while simultaneously overseeing the Northwest Indian War. In 1795, he retired to his estate in Thomaston, Maine, where he died in October 1806, at the age of 56. Today, many American towns, cities, counties, and military bases are named in his honor, including Knoxville, Tennessee, and Fort Knox in Kentucky.

Early Life

Henry Knox was born on 25 July 1750 in Boston, Massachusetts. He was the seventh of ten children born to William Knox and Mary Campbell, both of whom were Scotch-Irish Presbyterians who had emigrated to Boston in 1729. William Knox was a shipbuilder who, in 1759, was spurred on by financial troubles to abandon his family and move to Sint Eustatius in the West Indies to start a new life; his new life would not last long, however, as he died three years later of unknown causes. Henry, who was only nine years old when he was abandoned by his father, was now responsible for caring for his mother and younger siblings, and he eventually found a steady job as a clerk in a Boston bookstore.

The shopkeeper, Nicholas Bowes, became something of a father figure to Knox, encouraging the young clerk to take home books from the shop's extensive library to furnish his self-education. Knox soon became a voracious reader; with the help of the books in Bowes' shop, he educated himself in the topics of philosophy, mathematics, and even French, and spent his free time reading the works of classical literature. Yet Knox also took a special interest in military theory, reading everything he could get his hands on about tactics and military engineering. When he came of age in 1771, Knox opened a bookstore of his own called the London Book Store, which boasted a "large and very elegant assortment" of the newest books and magazines from London (McCullough, 58). Since Henry Knox's store offered a large selection of fashionable English products, it soon became a popular "morning lounge" for the Boston elite; the store, and Knox himself, soon became well-known throughout the city.

Revolutionary Fervor

Yet even as Knox's bookselling career was beginning to take off, he was unable to avoid getting entangled in the political unrest that was gripping Boston. The city had been the center of colonial protest against the unpopular Stamp Act and Townshend Acts, causing the British Parliament to send two regiments to Boston in 1768 to maintain royal authority. This only increased tensions, however, leading to the Boston Massacre of 5 March 1770, when nine British soldiers fired into a crowd of colonial protestors, killing five and wounding another eleven. The 20-year-old Knox witnessed the incident and had apparently tried to convince the soldiers to return peacefully to their quarters in the minutes leading up to the massacre. Knox was called to testify at the soldiers' trials in late 1770; skillfully defended by John Adams, all but two of the soldiers were ultimately acquitted.

In the months following the massacre, Henry Knox's own bookstore became a meeting place for both Loyalists and Patriots. It was known as a "great resort for British officers and Tory ladies" and was also frequented by Patriots like John Adams and Nathanael Greene, the latter of whom was also self-educated and talked with Knox at length about books and military matters. Despite being exposed to this mixture of political opinions, Knox firmly placed himself on the side of the Patriots. In 1772, he co-founded a militia unit, the Boston Grenadier Corps, and became increasingly involved with the Sons of Liberty, an underground group of political agitators who opposed Parliament's policies. In December 1773, when the cargo ship Dartmouth arrived in Boston Harbor carrying crates of British East India Company tea, the Sons of Liberty kept an armed guard to ensure that the ship did not unload the tea, which carried a Parliamentary tax. Although Knox was certainly one of these guards, it is unknown whether he went on to participate in the Boston Tea Party on the night of 16 December, when a party of Sons of Liberty climbed aboard Dartmouth and two other cargo ships and dumped 342 crates of tea into the harbor.

Shortly before his 23rd birthday in 1773, Knox was on a bird-hunting expedition on Noddle's Island in Boston Harbor when his fowling musket exploded in his hand. Although he managed to bind up the wound and rush to a doctor, the accident cost him two fingers on his left hand; for the rest of his life, Knox would always keep the hand wrapped in a handkerchief whenever he was in public. Around the same time, Knox fell in love with Lucy Fluckner, a young woman who frequented his bookstore. Lucy came from a family of prominent Loyalists – her father was the royal secretary of Massachusetts, and her brother would eventually serve in the British Army. Opposing politics was not enough to deter her from marrying Knox, which she did on 16 June 1774, over the protestations of her family. The couple would ultimately have 12 children.

Entering the Army

On 19 April 1775, the first shots of the Revolutionary War were fired at the Battles of Lexington and Concord. During the confusion that followed, Henry and Lucy Knox were able to escape from Boston in disguise shortly before New England militia forces laid siege to the British garrison within the city. Lucy settled in the nearby town of Worcester, never to see her Loyalist family again, as they would soon sail for England. Knox stayed in Worcester long enough to ensure his wife was settled before offering his services to General Artemas Ward, commander of the makeshift Patriot army carrying out the Siege of Boston. Commissioned as a colonel, Knox was put in charge of planning and building the Patriot fortifications. He also directed Patriot artillery at the Battle of Bunker Hill (17 June 1775).

On 2 July 1775, General George Washington arrived to take command of the army, which had been adopted by the Second Continental Congress and reorganized as the Continental Army. While inspecting the fortifications at Roxbury three days later, Washington first met Knox, who, at 25 years old, would have cut an imposing figure; standing six feet (182 cm) tall and weighing 250 pounds (113 kg), Knox had a deep, booming voice, a sociable demeanor, and an intelligent mind. He impressed Washington with his extensive military knowledge and was soon part of Washington's inner circle, frequently dining with the commander-in-chief and offering his thoughts on the ongoing siege.

Noble Artillery Train

One of the biggest obstacles the Patriots faced was that they did not have enough guns or powder to drive the British out of Boston. It was Knox who offered a solution: Fort Ticonderoga, which had recently been captured by Patriot forces under Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen, was home to a large quantity of both artillery and powder. Although the fort was over 300 miles (482 km) away in upstate New York, Knox was confident that the cannons could be hauled overland to Boston, where they could be positioned on the strategically significant Dorchester Heights; this vantage would give the Patriots a clear shot at the British troops inside Boston, who would have no choice but to evacuate. Washington agreed to the plan and put Knox in charge of the expedition, giving him a small escort of men and the authority to spend as much as $1,000.

On 5 December 1775, Knox arrived at Fort Ticonderoga. He selected 58 pieces of artillery, which included cannons, howitzers, and mortars, altogether weighing an estimated 120,000 pounds. The guns were first loaded onto boats and sailed down Lake George, which had not yet frozen over, a tedious process that took eight days. When he reached the southern end of the lake, Knox loaded the guns onto 42 sleds pulled by rented horses and, with the help of his soldiers (including his brother William) and some hired hands, hauled the cannons south. Hindered by heavy snowfalls, the expedition proceeded slowly, finally arriving at Albany, New York, on 4 January 1776.

From here, the expedition crossed the frozen Hudson River. During the crossing, one of the largest cannons fell through the ice, and Knox lost a full day retrieving it from the bottom of the river, which he managed with the "assistance [of] the good people of Albany" (quoted in McCullough, 84). On 9 January, the expedition moved on from the eastern banks of the Hudson and entered the Berkshires in western Massachusetts, passing through narrow valleys and difficult terrain. Finally, on 25 January, Knox's 'Noble Train of Artillery' arrived at Framingham, 20 miles (32 km) outside Boston; hundreds of men had taken part in the expedition at various points in the harrowing 300-mile trek, and no gun had been lost. The cannons were then positioned on Dorchester Heights, forcing the British to evacuate Boston on 17 March 1776; Knox's perseverance had given the Patriots one of their first major victories of the war.

Artillery Commander

After the Siege of Boston, Knox was tasked by Washington to lay out the defenses of Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New York City. He was with the Continental Army during the disastrous New York and New Jersey Campaign, during which the army was reduced by disease and desertion to barely 3,000 men. On the night of 25 December 1776, Knox was in charge of loading the soldiers, horses, and cannons into the boats in preparation for Washington's daring crossing of the Delaware River; Knox's booming voice could still be heard over the howling winter winds, and many soldiers credited the "extraordinary exertions" of Knox with the success of the crossing (quoted in McCullough, 274). The next morning, the Continental Army surprised and defeated a Hessian garrison at the Battle of Trenton. Knox was also with the army when it won another critical victory at the Battle of Princeton (3 January 1777).

For these efforts, Knox was promoted to brigadier general and given command of an artillery corps. During the early months of 1777, as the main army wintered in Morristown, New Jersey, Knox travelled to Springfield, Massachusetts, to establish an arsenal that would prove to be a vital source of ammunition for the Patriots. In June, Knox was outraged to learn that Congress had appointed a French officer, Tronson du Coudray, to command the Continental artillery; viewing the appointment as politically motivated, Knox threatened to resign and was supported by fellow generals Nathanael Greene and John Sullivan. When Washington wrote to Congress on Knox's behalf, he was reinstated as chief of artillery, and Coudray was reassigned to the position of Inspector General. Knox would go on to command the American artillery in many significant engagements such as the Battle of Brandywine (11 September 1777), Battle of Germantown (4 October 1777), and Battle of Monmouth (28 June 1778).

After Monmouth, a lull descended on the northern theater of the war, giving Knox time to establish a school for artillery and officer training in Pluckemin, New Jersey; this was the precursor of the United States Military Academy at West Point. When he was not training soldiers at this facility, Knox was often visiting state governments on Washington's behalf to secure promises for new recruits and material. In the autumn of 1781, he accompanied the army to Virginia and was present at the Siege of Yorktown (28 September to 19 October 1781) during which he played a pivotal role in directing the Continental artillery. He was promoted to major general on 22 March 1782, the youngest man to yet achieve that rank, and was given command over the crucial stronghold of West Point later that year.

In April 1783, Congress ordered the gradual demobilization of the Continental Army as American and British diplomats negotiated peace in Paris; Washington appointed Knox to command the day-to-day operations of the army and oversee the process of demobilization. When Washington resigned as commander-in-chief on 23 December 1783, Knox briefly held the position of senior officer of the army before also resigning from his military commission in early 1784. He also helped found the Society of the Cincinnati, a hereditary society for former Continental Army officers and their descendants.

Secretary of War

After the war, Knox returned to Massachusetts, where he reunited with Lucy and settled in the town of Dorchester. Yet he would soon return to public service when Congress selected him to succeed Benjamin Lincoln as Secretary of War on 8 March 1785. Under the Articles of Confederation, which governed the United States at the time, the federal government was kept weak to ensure the sovereignty of the states and was only allowed to maintain a small army. The war department that Knox inherited, therefore, consisted of only two civilian employees and one regiment. Believing that a stronger military was needed for the country's defense, Knox championed the establishment of an army comprised primarily of state militia as well as the creation of a military academy. While many in Congress were initially skeptical of the idea of a larger peacetime army, the outbreak of Shays' Rebellion (1786-87) caused many to advocate for a stronger federal military.

In 1788, the United States Constitution was ratified, replacing the Articles of Confederation and establishing a stronger central government. After his election to the presidency in 1789, Washington selected Knox as the first Secretary of War under the new government. In this capacity, Knox aligned himself with the Federalist Party of Alexander Hamilton and John Adams and sought to strengthen federal authority, particularly where the military was concerned. He focused his efforts on the creation of a strong, national militia; he spearheaded the passage of the Militia Act of 1792, which provided for the organization of such a militia and allowed for the president to take direct command during times of invasion or rebellion. Later that year, he would further strengthen the military with the creation of the Legion of the United States, a standing army of professional soldiers that would reduce the nation's reliance on unprofessional militias. Facing an arms shortage, Knox also urged Congress to import more European-produced weapons and established stockpiles of arms and ammunition at the arsenals of Springfield, Massachusetts, and Harper's Ferry, Virginia.

Henry Knox spent much of his tenure as Secretary of War prosecuting the Northwest Indian War against a united coalition of Native American nations known as the Northwestern Confederacy. In 1791, Knox organized a campaign against the Confederacy and appointed General Arthur St. Clair to lead it; this expedition was crushed by Indigenous warriors at the Battle of the Wabash, also known as St. Clair's Defeat, which is often recognized as the most total defeat ever suffered by an American army. Knox received a share of the blame for the disaster, leading him to work tirelessly to win a victory against the natives and restore his reputation before leaving office. These efforts paid off on 20 August 1794, when General 'Mad' Anthony Wayne led the Legion of the United States to victory against the Northwestern Confederacy at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. This victory led to the Treaty of Greenville, in which the Native Americans were forced to cede lands in Ohio to the United States.

Later Life

On 31 December 1794, Henry Knox left his post as Secretary of War and retired to the large estate he had purchased in Thomaston, Maine, upon which he built a 3-story mansion called Montpellier. Using the connections he had made in government, he engaged in land speculation, buying large plots of territory in Maine as well as in the Ohio Valley. Knox became known as a ruthless landlord, not hesitating to evict tenants who could not pay rent. One of the men Knox took land from was Joseph Plumb Martin, a Revolutionary War veteran who had settled in Maine. Incidents like this made Knox so unpopular that he lost his seat in the Massachusetts General Court, where he had briefly served as representative of Thomaston. Still, Knox enjoyed a large fortune and a comfortable retirement until his death on 25 October 1806 at the age of 56. He was buried with full military honors on his Thomaston estate and was survived by his wife Lucy Fluckner Knox, who died in 1824.